After art school (Rhode Island School of Design, BFA ’93), I started a somewhat unintentional journey to find a home and to see the country. Nearly fifteen years ago, my wife, a violinist and teacher, and I settled in Portland, Oregon. Along the way, we lived in the south, the mountain west, and probably some places in between. To fill in the blanks and empty my head, the motorcycle became my tool to explore the landscape and I put many a mile on one motorcycle or another.

Today’s story that will shape our lives for years to come is that of our young daughter, Jane. A beautiful bundle of laughter, Jane was born with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome, a rare and dangerous heart defect that has required multiple life-saving surgeries and will require more in the future. It has been difficult and consuming. She has a long and uncertain road ahead but today she is thriving and adorable.

Throughout all of this, the urge has been to paint. It is what I do and what I am. That I’m painting better than ever is no small thing.

In the Studio: Scott Conary

November 2017 – Allison Malafronte

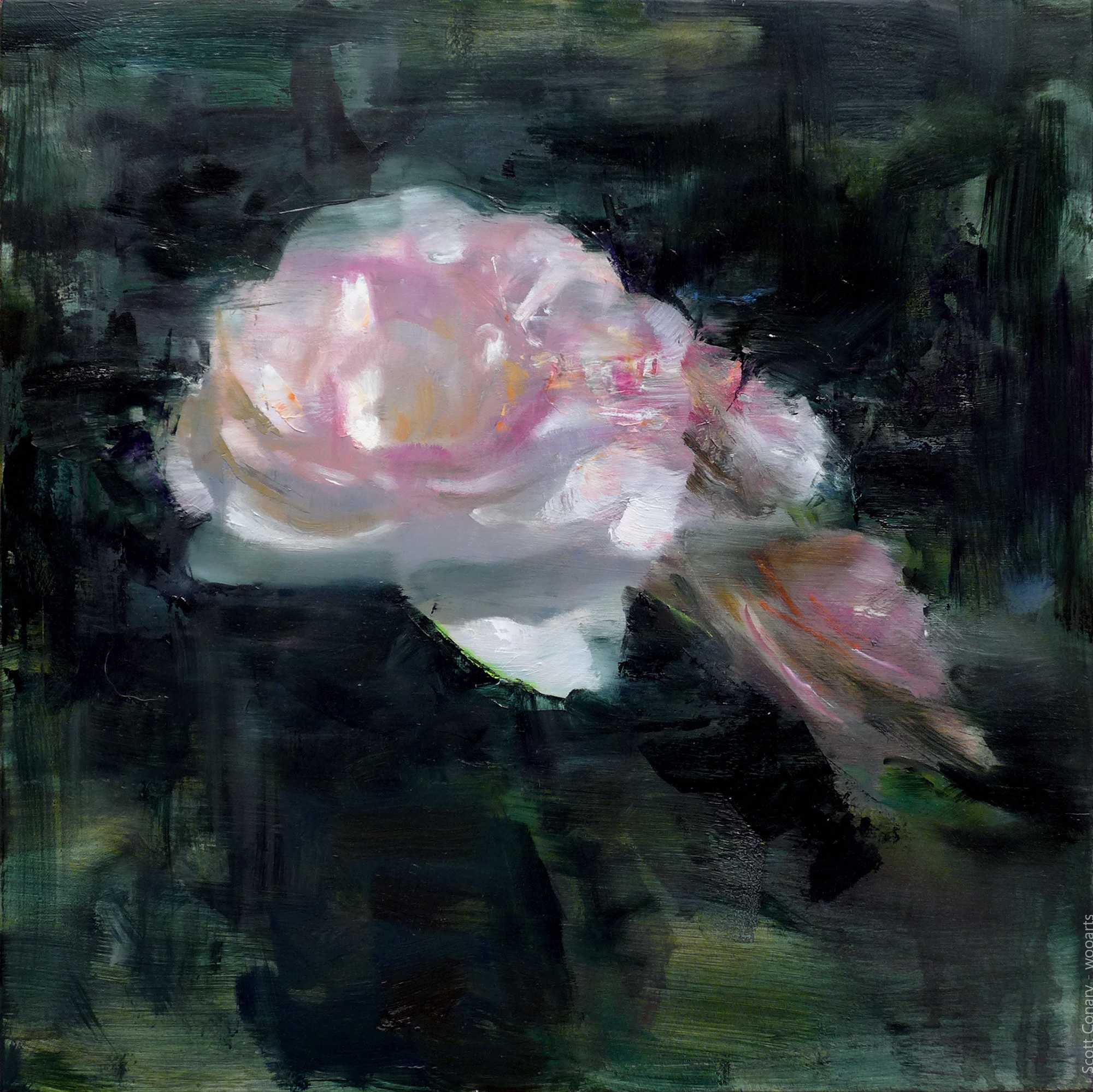

One look at Scott Conary’s paintings, and it’s clear that he is an artist who is fluent not only in fine art but also design. His textured constructions of simple forms collide in space with striking yet soothing passages of abstract color, all placed with painterly finesse and a designer’s instinct. Amid this strategic harmony is the artist’s yielding to the unpredictability of the painting process, which allows for impromptu happenstance and the occasional happy accident. Conary has been walking the fine line between realism and abstraction, and painting and design, from the beginning of his training. He received his B.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design, and from a young age he was able to identify and pursue an artistic philosophy that best suited his temperament. Along the way, he was profoundly influenced by such artists as Diebenkorn, DeKooning, and Giacometti, as well as by an early exposure to the work of N.C. Wyeth and Andrew Wyeth during his childhood in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Those lasting impressions, coupled with Conary’s personal experiences later in life—especially the difficulty of watching his beloved, bubbly seven-year-old daughter battle complicated heart defects from birth—fuels his desire to create something of substance in his work, and to show beauty in brokenness and ambiguity. In this Q+A, Conary speaks candidly about those struggles and joys, as well as about his ongoing explorations and discoveries in paint.

AM: When you went to Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) for your undergraduate, were you planning at that point to work in the design field, or fine art?

SC: My assumption was that I was going to be an illustrator of some kind. I went to high school outside of Chicago and spent a fair amount of time wandering through the city’s galleries and museums. Because of what I saw, and my parents’ preaching of pragmatism, I couldn’t imagine for a moment that I would ever be a so-called “fine artist.” I wanted to draw and paint things that looked like things, and I had little patience for or understanding of the opaque language and often clinical work in those galleries and museums. But then I went to RISD and, bit by bit, my assumptions fell apart.

AM: I know a few traditional painters who went to RISD and eventually felt they had to find additional training in order to learn how to paint “realistically.” Did you have additional training after RISD, or were you largely self-taught from that point on?

SC: I know some that sought additional training, and benefited from it, but I never felt a strong need to pursue that myself. Or rather, I believed that most of my questions and doubts—both because of the foundation I had received at RISD and my own temperament—could be best answered by more work and more living. That isn’t to say that I was or am in some way better or more advanced; but that I, often to my own frustration, need to do things on my own terms and am more successful when I do. This is also why I am not an illustrator. It is a shoe that does not fit this foot.

Some have expressed dissatisfaction with the education they did or did not receive at schools such as RISD, and it isn’t for everyone. But that education was overall an excellent experience for me. I was fortunate to connect and work with some remarkable like-minded professors and students who covered a wide range of visual expression. From the start, the emphasis was on developing an eye and voice as well as a hand, and recognizing that they all feed one another. Between a certain amount of adolescent defiance, work as a teaching assistant in foundation drawing, taking as many independent studies as was allowed, and those critical relationships, I largely carved out my own path in college and found the roots of my artistic philosophy.

AM: The style that you’re painting in now, this wonderful hybrid of representation and abstraction, was that always the way you painted? Or were you at one point much more abstract or much more realistic? What caused the shift?

SC: The short answer is yes. I’ve long tried to straddle the representational and abstract. The somewhat longer answer is that while I ricocheted as much as any young artist trying to find my way, some of the artwork I was exposed to early on had a profound influence on how I think about painting. About how the image, the surface, materials, and the process of painting can come together in some kind of evocative whole that is more than the sum of the parts. There was a time when I would have said it was something I found after discovering artists such as Diebenkorn, and seeing the connection between a Rembrandt or Ingres drawing and the abstractions of Klein and DeKooning. There is some truth in that, but it goes back farther. First, for my young eyes, there were the Wyeths and then there was Giacometti.

As for the former, for as long as I can remember, I’ve been looking at Wyeth paintings: primarily N.C. and Andrew. My grandmother lived in northern Delaware, and for a handful of years we lived in Chadds Ford and the surrounding area. The Brandywine River Museum was a fixture in my life. To artist-friends, I might possibly brag that I used to canoe and fish around the Wyeth farm and that I might know where some of those houses from Andrew’s paintings are. The work of the entire Wyeth clan, in different ways, shows a stunning sense of the abstract. (Although I didn’t understand it at the time.) Much has been said about N.C.’s use of color, but I’ve always been impressed with the way he balanced the big and often murky or turbulent, against nuggets of information. There are these shimmering passages of light and dark breathing shadows against intersections of intensity. Many of his decisions might have been driven by deadlines and the need for efficiency, but the results are, again, stunning—and all while presenting a specific, dramatic image.

Andrew of course presents a more contemplative world and is best known for his fastidious depictions. But his use of materials, however tiny the marks may be, is right up there with almost any abstract expressionist. Instead of the large and muscular—although that can be found in his watercolors—it’s been woven into compelling images with deceptive geometry. Just last week I was standing in front of one of his paintings. It included a barn in a snowy field with a wintry, bare stand of woods on the horizon. It is the expected Andrew Wyeth painting. It was a chorus of angles and planes moving your eye around and around, all creating a powerful sense of place that included crackling details and subtle light.

Again, I didn’t understand the balancing act the Wyeths were engaged in. In my youth, I saw great paintings of exciting pirates and the landscape I considered home. Giacometti, although I didn’t realize it until recently, was my key. In high school we’d go down to the Art Institute of Chicago and marvel at its collection. Although I had an adolescent affinity for Bacon and Albright, and admired the candlelit articulations of the Old Masters, it was a Giacometti portrait that I couldn’t resist and that I would seek out on every visit. I certainly didn’t understand it: this peculiar, scribbling, carving, incisive (but, from a traditional point of view, murky and incomplete) painting. It was, however, a revelation. It sang the possibility, the necessity, of painting as an earnest process and uncertain investigation rather than a methodical craft. He showed that creating a presence wasn’t necessarily about capturing light and specifics or being a better camera, in some expressive way. That it lay somewhere else. It’s what I see in the best work of my heroes. It took me years (decades?) to understand what this piece sparked and how it fit into what’s come since.

White Tea (Bok Choy), by Scott Conary, oil on panel, 10 x 10 in.AM: Among other strengths, your abilities with color is a standout. Is working with color the most enjoyable aspect of painting for you?

SC: My paintings tend to have a fair amount of structure (quite literally in the case of the architectural pieces). With that framework, comes the freedom to push different aspects of the work. Color can then be everything from the confetti to the meat of a piece. But I take a somewhat holistic view of painting where mark, color, value, and all the other pieces are one and the same. And when a painting finally starts to smolder, and I’m trying to get it to fully ignite, I’m grabbing whatever kindling is at hand and it tends to not fall neatly into different categories. Having said that, when I step back and look at my work more objectively, it’s clear that I must have a need to return to that first box of Crayolas. In many paintings there’s one or two strong colors stealing the show that are almost straight out of that box. I’m a sucker for a strong red or blue.

AM: What would you say is your greatest strength as a painter? Your greatest weakness?

SC: To both: obsessiveness. It’s how the best paintings get made. I’ll marinate in an idea and try to push, sometimes into the wee hours and sometimes for years, an OK painting into being something better. Sometimes I get hopelessly stuck.

AM: Who are some of the other artists of the past you admire the most? The present?

SC: It’s a pretty typical parade of Degas, DeKooning, Wyeth, Rembrandt, Medardo Rosso, Kollwitz, Goya, Diebenkorn, Rodin, et al. It can be difficult to discern what has inspired and which simply demands attention. Degas floors me, but then I’ll giddily yawp in front of a DeKooning or Wyeth. For artists of the present, social media, as you know, puts so many artists right at our fingertips. On any given day, I might look at the work of and converse with Kathleen Speranza, Quang Ho, Mia Bergeron, Mark Daniel Nelson, David Sharpe, Catherine Kehoe, my old confidant Shawn Kenney, and many others. Maybe too many. This is without touching on titans such as Desiderio or Antonio López García. I do try to manage my consumption lest I get distracted or pick up a strange accent.

AM: Where is inspiration coming from these days for you? What inspired the last painting you painted?

SC: The last painting of note was of an old Pennsylvania farmhouse, a centuries-old structure on a dairy farm not far from the Brandywine River and in the midst of Wyeth country. It was another turning point, and I never thought I’d finish it. It reminded me that the phrase “it’s not what you paint but how you paint it” just isn’t true for me, as well as a reminder of the necessity of painting while an impulse is still breathing. When I started, my intent was to paint a beautiful thing with big attractive shapes, but I instead fell in love with the story of the windows, of the spaces where people had lived full lives, and so on. Having let that original intent fall away, it took me awhile to untangle what I wanted out of the painting. Beyond that, I’m working on a series of paintings more directly about our experiences in the hospital. They’re pieces I’ve wanted to make, but they required room in my head and life that has only recently become available.

AM: Because you seem to be painting in an interestingly unique way, can you please briefly describe your process?

SC: If I see a difference in how I work as compared to some other artists, it’s that I approach painting as a sculptural process as much as a consideration of light, color, mark, and so on. It’s a repeated gathering, building up, and tearing down of material. I use a brush, painting knife, old credit card, brayer, splash of solvent, my hand. Most anything. Whatever it takes to uncover and build that tenuous sense of weight, presence, and mystery that I’m looking for. This approach, as it strips down the subject and knits the painting together, can make it feel real in a way that a more deliberative, tidy, and accurate rendering may not. This also means that while a painting might happen in a session or two, I might wrestle with it for years.

The best paintings start with an impulse and destination in mind, but for which I don’t necessarily know the route from start to finish. If an object is small enough, I’ll paint it directly in the studio. If something is large, such as a house, I’ll do some sketches in the field, possibly a color study or two, and take many photographs. I’ll play with those photos on the computer, make a pile of sketches, move elements around, get fixated on a size, and start the painting. For both kinds of scale, I’ll usually realize that what made sense on the screen or in a sketch often doesn’t quite make sense in a painting — and I’ll start over. This can go on for longer than I like to admit.

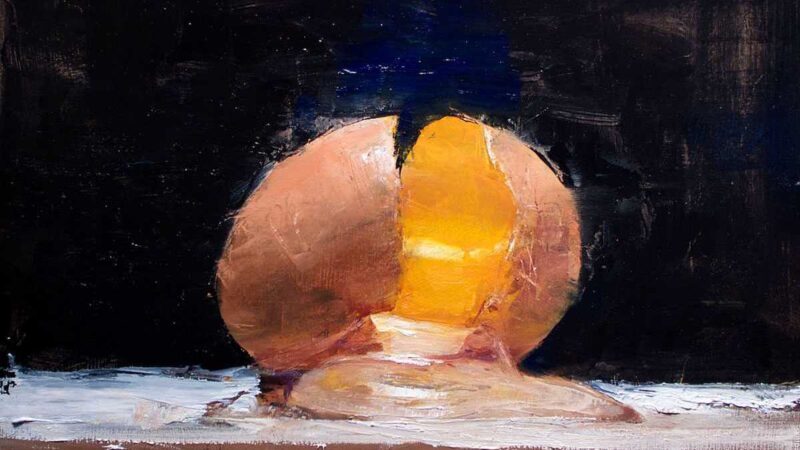

Students are sometimes alarmed by this tearing down, but it’s part of the process. But those apparent false starts are necessary. They expand my understanding of the subject and all that excavation will make the final piece come together stronger and with a clearer purpose. Ideally each painting is a new experience, and this approach can give a vitality that might be missing if I knew the exact route. Or so I tell myself. Most times when I’ve tried a shortcut, using as many assumptions as I can and letting my focus move too far forward, I have not been happy with the result. Admittedly, I have a sketch book full of scribbles of ovals in rectangles as I’ve tried to figure out how to paint another egg.

AM: I notice in some of your subject matter that fragile things—eggs, pottery, run-down buildings, etc.—are presented as cracked or fractured, but not fully broken. There is also incredible beauty in the near brokenness. What experiences or observations in your life are you drawing these metaphors from?

SC: When I paint, for example, a broken egg, it is in many ways a painting of our remarkable daughter, Jane. Of a perfect object, full of contradictions, now apparently broken and difficult but still so beautiful. Of the promise of a future misplaced and the sublime of the moment. A giggling, complicated, bundle of blonde adorableness and, especially lately, attitude, Jane has endured multiple, complex open-heart surgeries, experiences disability, and has an uncertain future. We spent her first few years in and out of the hospital, often not knowing if she’d survive to see another tomorrow. Today, some of our concerns are different from those of other parents, and we live a peculiar existence with a quiet but perpetual terror that today is her last day. All of this has changed our lives, our careers, and our perspective. It has also driven much of my recent work, and fueled how I think about the specific or implied narrative. We continue to adapt and embrace, with changing levels of success, the everyday joy and mundanity of family life. Jane is, as I write this, in second grade probably giggling at the antics of her classmates.

View Scott Conary Paintings