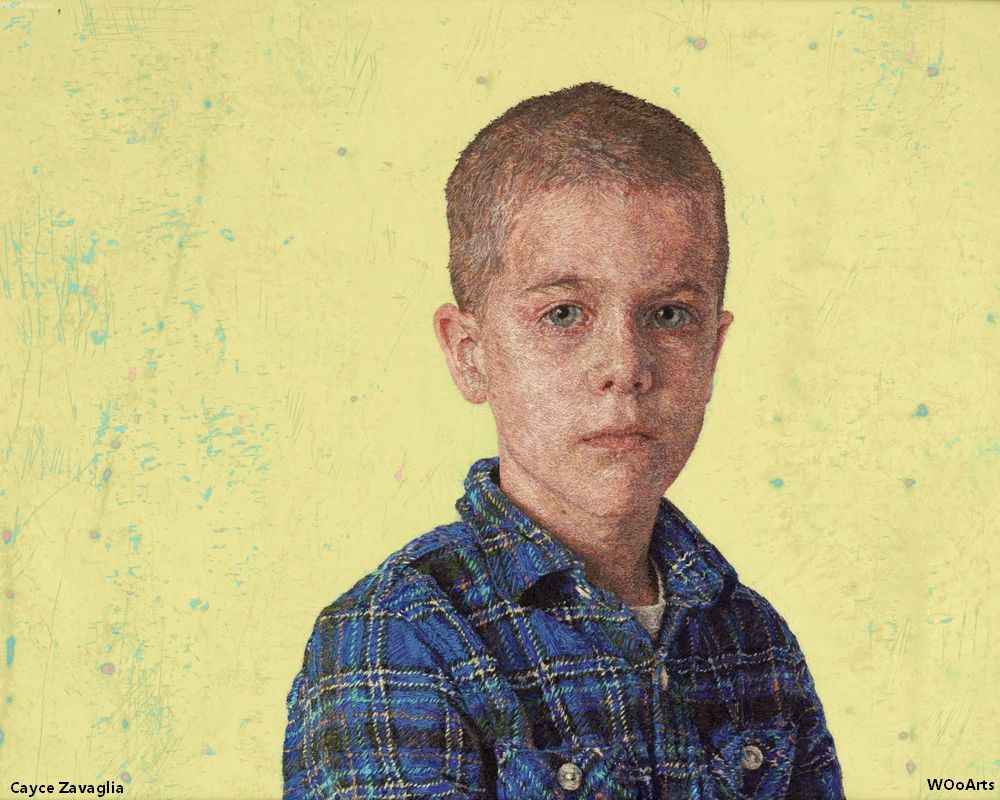

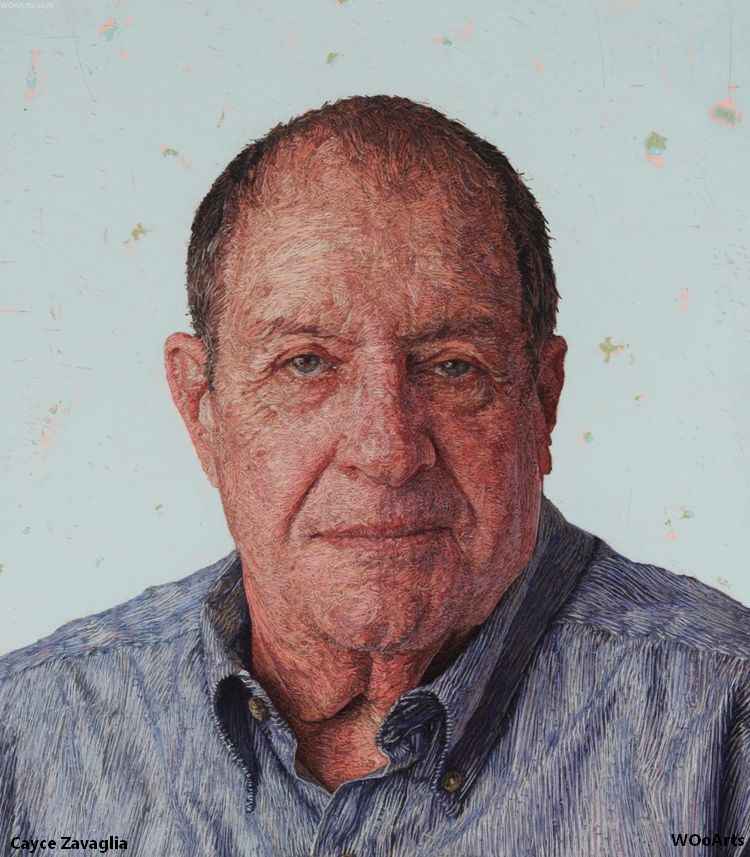

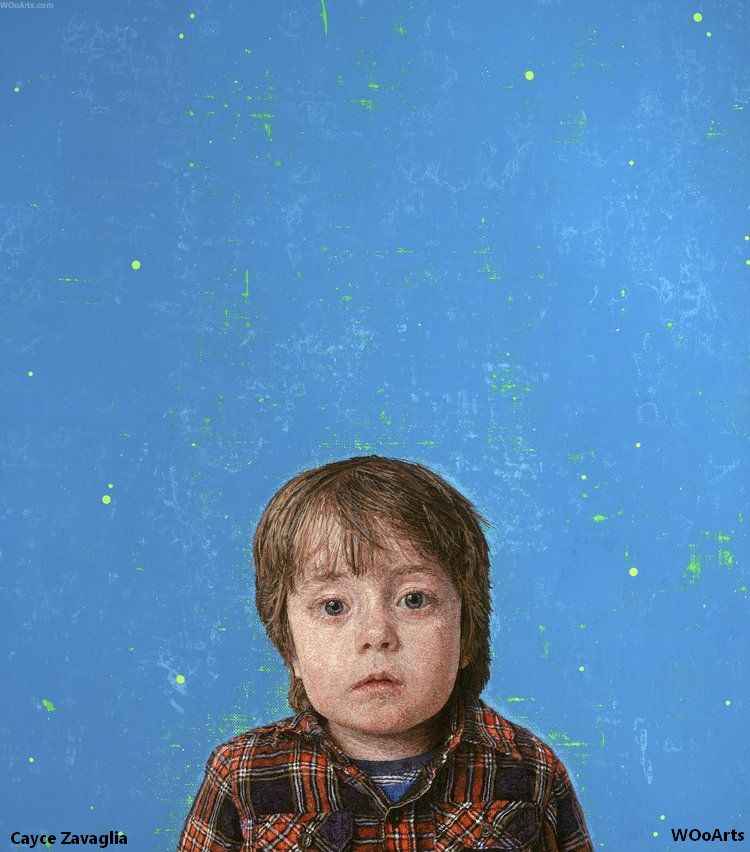

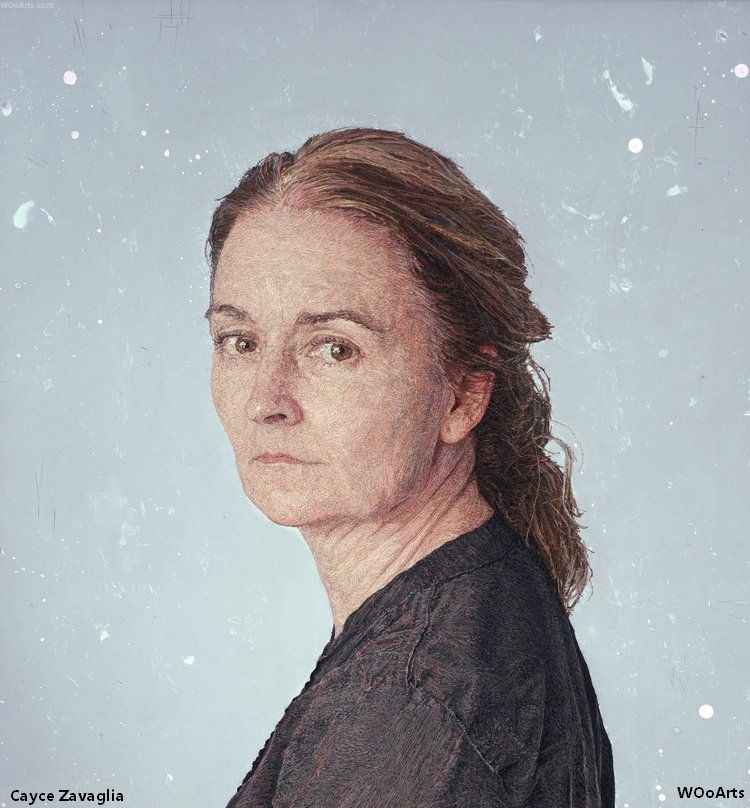

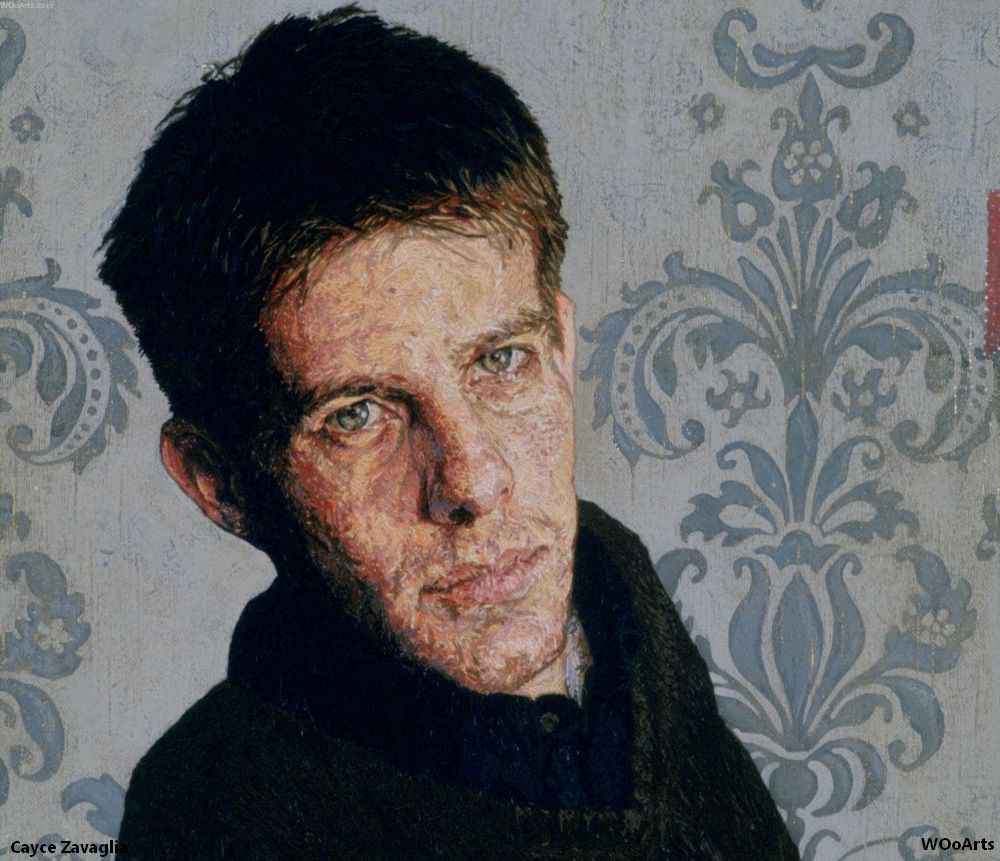

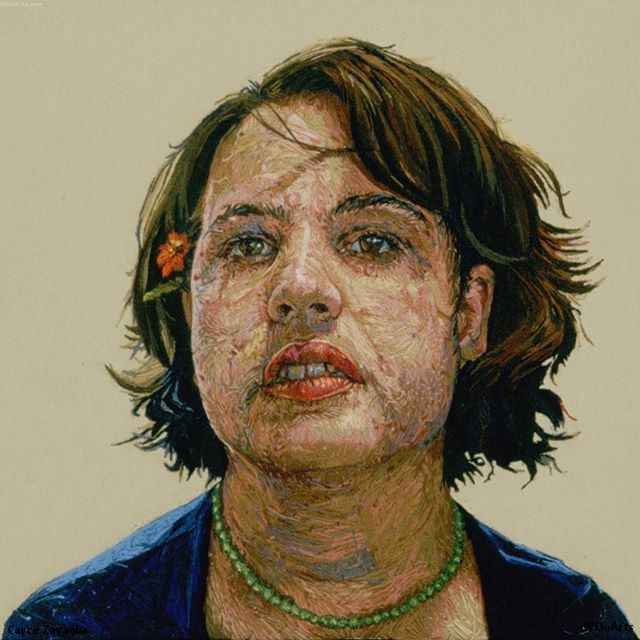

The gaze of the portrait toward the viewer has remained constant over the years and in my work…as has my search for a narrative based on both faces and facture. The work is all hand sewn using cotton and silk thread or crewel embroidery wool. From a distance they read as hyper-realistic paintings, and only after closer inspection does the work’s true construction reveal itself.

Over the years, I have developed a sewing technique that allows me to blend colors and establish tonalities that resemble the techniques used in classical oil painting. The direction in which the threads are sewn mimic the way brush marks are layered within a painting which, in turn, allows for the allusion of depth, volume, and form.

My stitching methodology borders on the obsessive, but ultimately allows me to visually evoke painterly renditions of flesh, hair, and cloth.

A few years ago, I turned one of my embroideries over and for the first time saw the possibilities of a new image and path for my work that had been with me in the studio for so long but had gone unnoticed.

It was the presence of another portrait that visibly was so different from the meticulously sewn front image, but perhaps more psychologically profound. The haphazard beauty found in this verso image created a haunting contrast to the front image and was a world of loose ends, knots, and chaos that could easily translate into the world of paint.

This discovery led to a “return to paint” in my work and the production of a series of intimate gouache and large format acrylic paintings of these verso images. Highlighting the reverse side of my embroideries, which historically and traditionally has been hidden from the viewer, has initiated a conversation about the divergence between our presented and private selves.

The production of both Recto and Verso images is now the primary focus of my studio work.

CAYCE ZAVAGLIA

b. 1971 Valparaiso, IN

EDUCATION

1998 MFA (Painting), Washington University, Saint Louis, MO

1994 BA (Painting), Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL

EXHIBITIONS

2019 Current Profile, Craft Alliance Center of Art and Design, Saint Louis, MO

2018 Southerly, (Solo Exhibition), Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

EXPO Chicago, William Shearburn Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

Art Miami, William Shearburn Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

2017 Likeness, William Shearburn Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

Art Miami, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

EXPO Chicago, William Shearburn Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

2016 EXPO Chicago, William Shearburn Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

Art Miami, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

2015 About-Face, (Solo Exhibition), Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

2014 Recto/Verso, (Solo Exhibition) Contemporary Art Museum, Saint Louis, MO

2013 String Theory, Scott White Contemporary Art, La Jolla, CA

2012 Art Miami, (Solo Exhibition) Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Resourced, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

2011 PULSE Miami, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Multiple Stitches: Cayce Zavaglia, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Here and Now, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Story Lines: Contemporary Embroidery, Craft Alliance, Saint Louis, MO

2010 Cutting Edge, Textile Arts Center, Brooklyn, NY

2009 PULSE Miami, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Painting with Wool: New Embroidered Portraits, (Solo Exhibition)

Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

Giving Face, Nicholas Robinson Gallery, New York, NY

Narrative Thread, Lyons Wier Gallery, New York, NY

PULSE New York, Lyons Wier Ortt Gallery, New York, NY

2008 As Others See Us: The Contemporary Portrait, Brattleboro Museum and Art Center,

Brattleboro, VT

Summer Salon, Lyons Wier Ortt Gallery, New York, NY

PULSE New York, Lyons Wier Ortt Gallery, New York, NY

2007 Material Attitudes, Regional Arts Commission, Saint Louis, MO

2005 About Faces: Portraits Past and Present, Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences, Staten

Island, NY

2004 Women Only, Elliot Smith Contemporary Art, Saint Louis, MO

PUBLICATIONS

Portrait Magazine, National Portrait Gallery Australia, March 2017

Luxe Interiors + Design Magazine, Fall 2016

Surface Design Magazine, Summer 2012

Elle Décor, Artist Profile, April 2012

PUSH Stitchery, Lark Crafts/Sterling Publishing, 2011

Iconography of the Self, Fiber Arts Magazine, Summer 2011

New American Paintings: Volume 89, 2010

New American Paintings: Volume 53, 2004

Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, 05/09/04

COLLECTIONS

21c Museum – Louisville, KY

Miniature Museum at Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

Schoeni Gallery, Hong Kong

University of Maine Museum of Art, Bangor, ME

West Collection, Oaks, PA

GALLERY REPRESENTATION

Lyons Wier Gallery

542 West 24th Street, New York, NY 10011

Tel: 212.242.6220

www.lyonswiergallery.com

William Shearburn Gallery

665 S Skinker Blvd, St Louis, MO 63105

Tel: 314.367.8020

www.shearburngallery.com

What is Embroidery?

Embroidery is the craft of decorating fabric or other materials using a needle to apply thread or yarn.

Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as pearls, beads, quills, and sequins. In modern days, embroidery is usually seen on caps, hats, coats, blankets, dress shirts, denim, dresses, stockings, and golf shirts. Embroidery is available with a wide variety of thread or yarn color.

Some of the basic techniques or stitches of the earliest embroidery are chain stitch, buttonhole or blanket stitch, running stitch, satin stitch, cross stitch. Those stitches remain the fundamental techniques of hand embroidery today.

The Embroidery history:

Origins

The process used to tailor, patch, mend and reinforce cloth fostered the development of sewing techniques, and the decorative possibilities of sewing led to the art of embroidery. Indeed, the remarkable stability of basic embroidery stitches has been noted:

It is a striking fact that in the development of embroidery … there are no changes of materials or techniques which can be felt or interpreted as advances from a primitive to a later, more refined stage. On the other hand, we often find in early works a technical accomplishment and high standard of craftsmanship rarely attained in later times.

The art of embroidery has been found worldwide and several early examples have been found. Works in China have been dated to the Warring States period (5th–3rd century BC). In a garment from Migration period Sweden, roughly 300–700 AD, the edges of bands of trimming are reinforced with running stitch, back stitch, stem stitch, tailor’s buttonhole stitch, and whip-stitching, but it is uncertain whether this work simply reinforced the seams or should be interpreted as decorative embroidery.

Ancient Greek mythology has credited the goddess Athena with passing down the art of embroidery along with weaving, leading to the famed competition between herself and the mortal Arachne.

Historical applications and techniques

Depending on time, location and materials available, embroidery could be the domain of a few experts or a widespread, popular technique. This flexibility led to a variety of works, from the royal to the mundane.

Elaborately embroidered clothing, religious objects, and household items often were seen as a mark of wealth and status, as in the case of Opus Anglicanum, a technique used by professional workshops and guilds in medieval England. In 18th-century England and its colonies, samplers employing fine silks were produced by the daughters of wealthy families. Embroidery was a skill marking a girl’s path into womanhood as well as conveying rank and social standing.

Conversely, embroidery is also a folk art, using materials that were accessible to nonprofessionals. Examples include Hardanger from Norway, Merezhka from Ukraine, Mountmellick embroidery from Ireland, Nakshi kantha from Bangladesh and West Bengal, and Brazilian embroidery. Many techniques had a practical use such as Sashiko from Japan, which was used as a way to reinforce clothing.

The Islamic world

Embroidery was an important art in the Medieval Islamic world. The 17th-century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi called it the “craft of the two hands”. Because embroidery was a sign of high social status in Muslim societies, it became widely popular. In cities such as Damascus, Cairo and Istanbul, embroidery was visible on handkerchiefs, uniforms, flags, calligraphy, shoes, robes, tunics, horse trappings, slippers, sheaths, pouches, covers, and even on leather belts. Craftsmen embroidered items with gold and silver thread. Embroidery cottage industries, some employing over 800 people, grew to supply these items.

In the 16th century, in the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, his chronicler Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak wrote in the famous Ain-i-Akbari: “His majesty (Akbar) pays much attention to various stuffs; hence Irani, Ottoman, and Mongolian articles of wear are in much abundance especially textiles embroidered in the patterns of Nakshi, Saadi, Chikhan, Ari, Zardozi, Wastli, Gota and Kohra. The imperial workshops in the towns of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur and Ahmedabad turn out many masterpieces of workmanship in fabrics, and the figures and patterns, knots and variety of fashions which now prevail astonish even the most experienced travelers. Taste for fine material has since become general, and the drapery of embroidered fabrics used at feasts surpasses every description.”

Automation

The development of machine embroidery and its mass production came about in stages in the Industrial Revolution. The earliest machine embroidery used a combination of machine looms and teams of women embroidering the textiles by hand. This was done in France by the mid-1800s. The manufacture of machine-made embroideries in St. Gallen in eastern Switzerland flourished in the latter half of the 19th century.

Classification

Embroidery can be classified according to what degree the design takes into account the nature of the base material and by the relationship of stitch placement to the fabric. The main categories are free or surface embroidery, counted embroidery, and needlepoint or canvas work.

In free or surface embroidery, designs are applied without regard to the weave of the underlying fabric. Examples include crewel and traditional Chinese and Japanese embroidery.

Counted-thread embroidery patterns are created by making stitches over a predetermined number of threads in the foundation fabric. Counted-thread embroidery is more easily worked on an even-weave foundation fabric such as embroidery canvas, aida cloth, or specially woven cotton and linen fabrics . Examples include cross-stitch and some forms of blackwork embroidery.

While similar to counted thread in regards to technique, in canvas work or needlepoint, threads are stitched through a fabric mesh to create a dense pattern that completely covers the foundation fabric. Examples of canvas work include bargello and Berlin wool work.

Embroidery can also be classified by the similarity of appearance. In drawn thread work and cutwork, the foundation fabric is deformed or cut away to create holes that are then embellished with embroidery, often with thread in the same color as the foundation fabric. When created with white thread on white linen or cotton, this work is collectively referred to as whitework. However, whitework can either be counted or free. Hardanger embroidery is a counted embroidery and the designs are often geometric. Conversely, styles such as Broderie anglaise are similar to free embroidery, with floral or abstract designs that are not dependent on the weave of the fabric.

Materials

The fabrics and yarns used in traditional embroidery vary from place to place. Wool, linen, and silk have been in use for thousands of years for both fabric and yarn. Today, embroidery thread is manufactured in cotton, rayon, and novelty yarns as well as in traditional wool, linen, and silk. Ribbon embroidery uses narrow ribbon in silk or silk/organza blend ribbon, most commonly to create floral motifs.

Surface embroidery techniques such as chain stitch and couching or laid-work are the most economical of expensive yarns; couching is generally used for goldwork. Canvas work techniques, in which large amounts of yarn are buried on the back of the work, use more materials but provide a sturdier and more substantial finished textile.

In both canvas work and surface embroidery an embroidery hoop or frame can be used to stretch the material and ensure even stitching tension that prevents pattern distortion. Modern canvas work tends to follow symmetrical counted stitching patterns with designs emerging from the repetition of one or just a few similar stitches in a variety of hues. In contrast, many forms of surface embroidery make use of a wide range of stitching patterns in a single piece of work.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embroidery

Gallery