A Dive into the Enigmatic Palette of Benito Quinquela Martín: Unveiling the Artistic Brilliance

Benito Quinquela Martín’s art style is a captivating fusion of vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and a profound connection to the human experience. Through his works, he has immortalized the spirit of La Boca and created a visual legacy that transcends time. Quinquela Martín’s ability to intertwine aesthetics with social commentary sets him apart as a true master of his craft, leaving an enduring impact on the world of art.

Benito Quinquela Martín, a luminary in the world of art, has left an indelible mark on the canvas of Argentine culture. Renowned for his vibrant and evocative depictions of life in La Boca, his art style has become a testament to his mastery of expression. In this critique, we explore the nuances of Quinquela Martín’s distinctive art style, delving into the elements that make his works timeless.

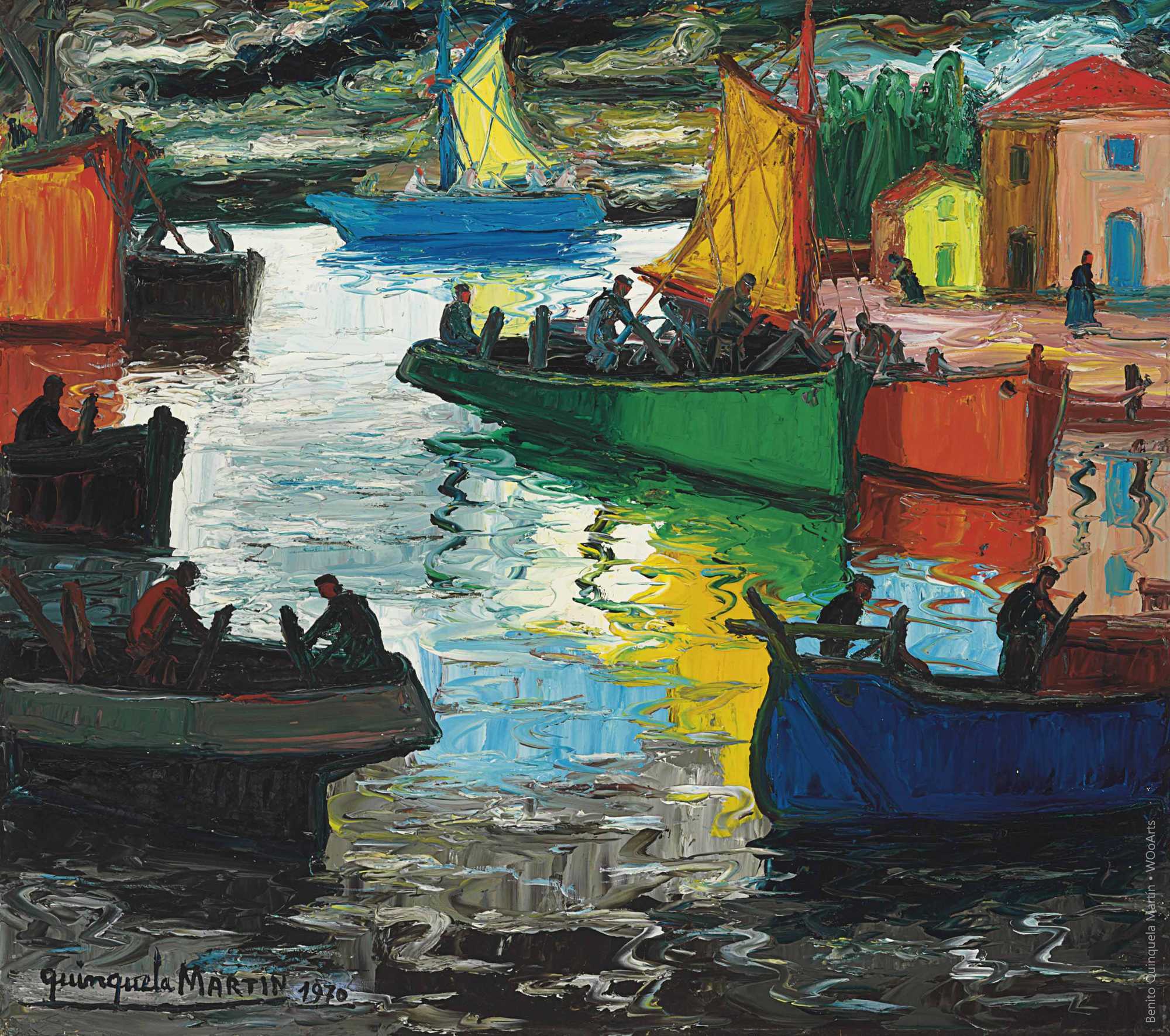

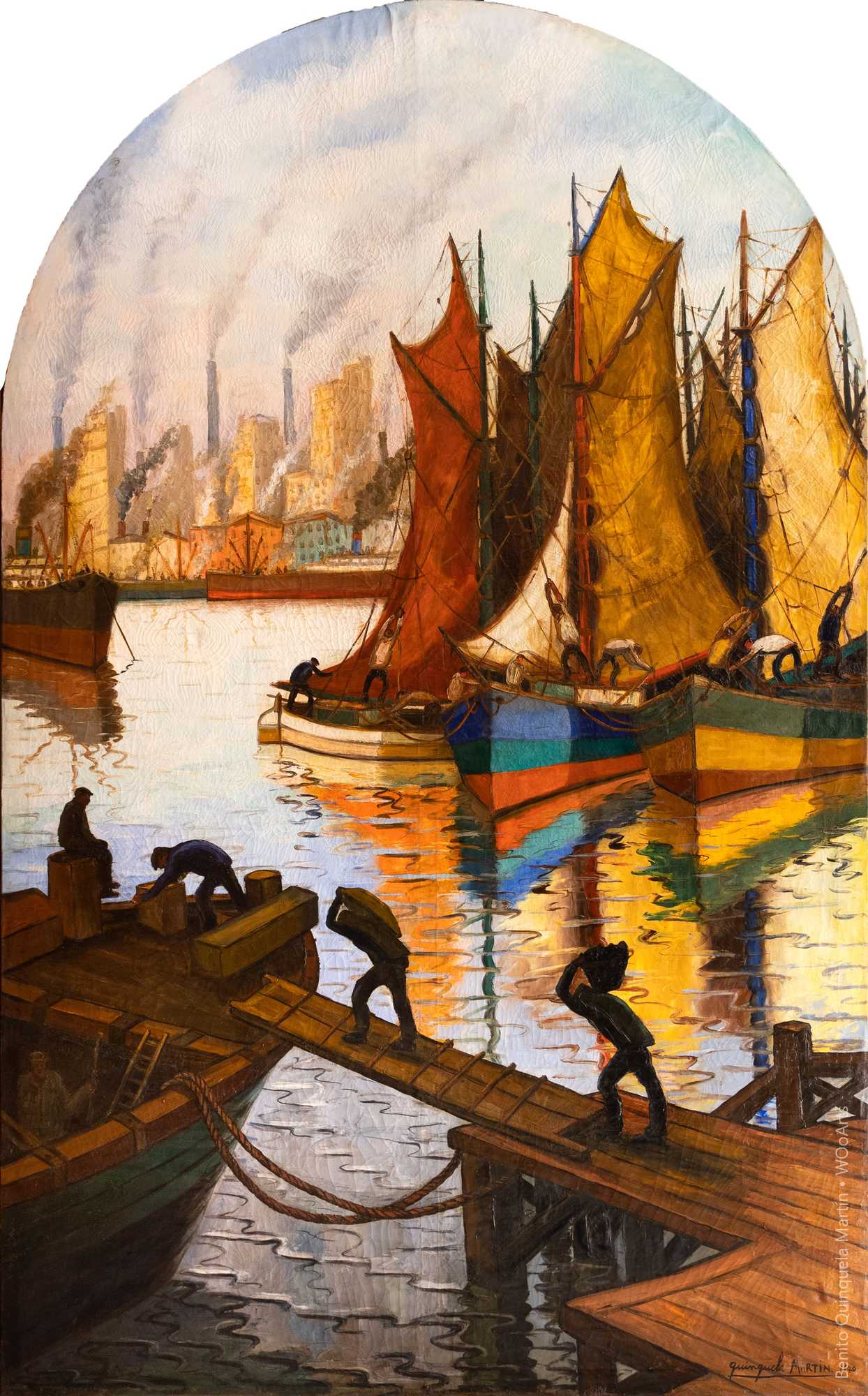

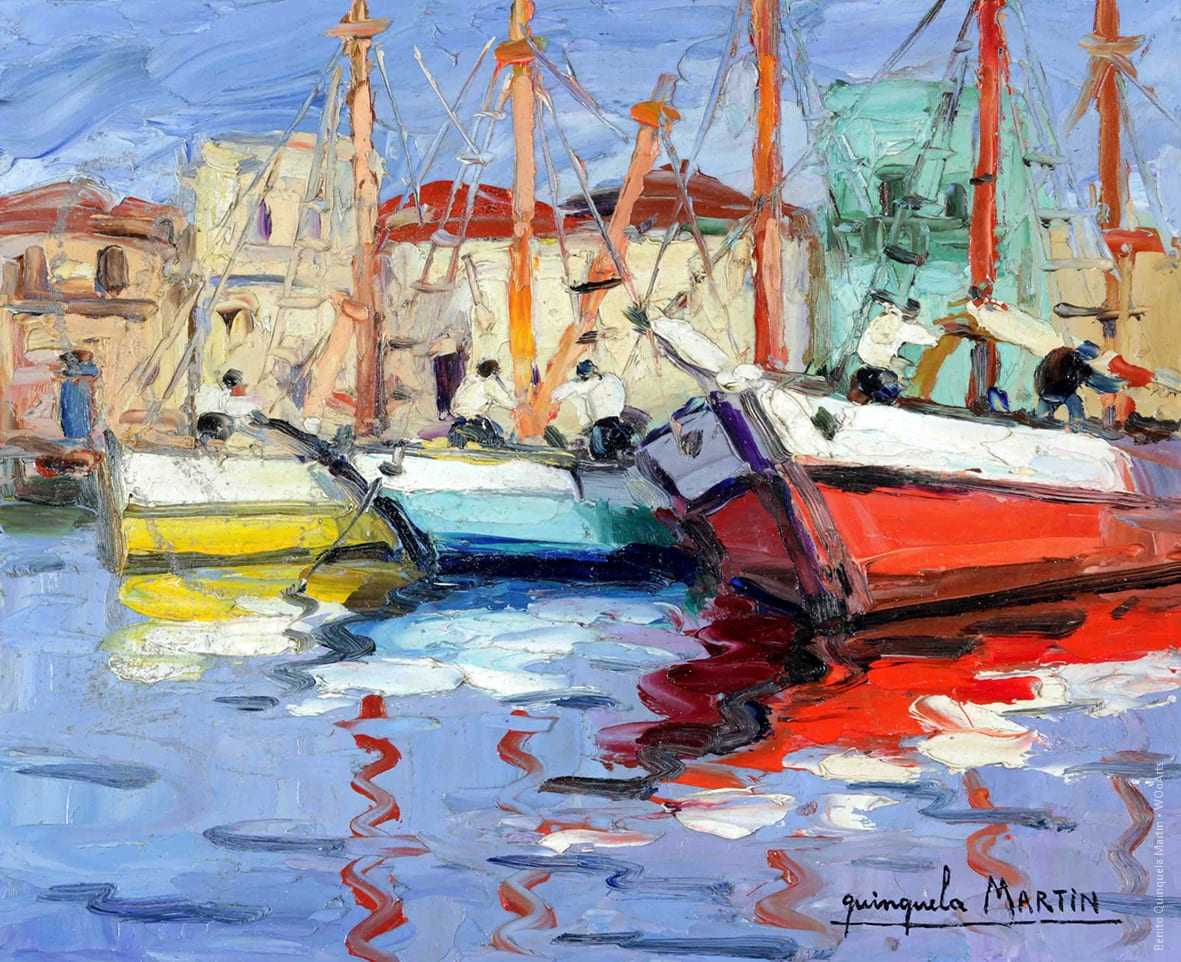

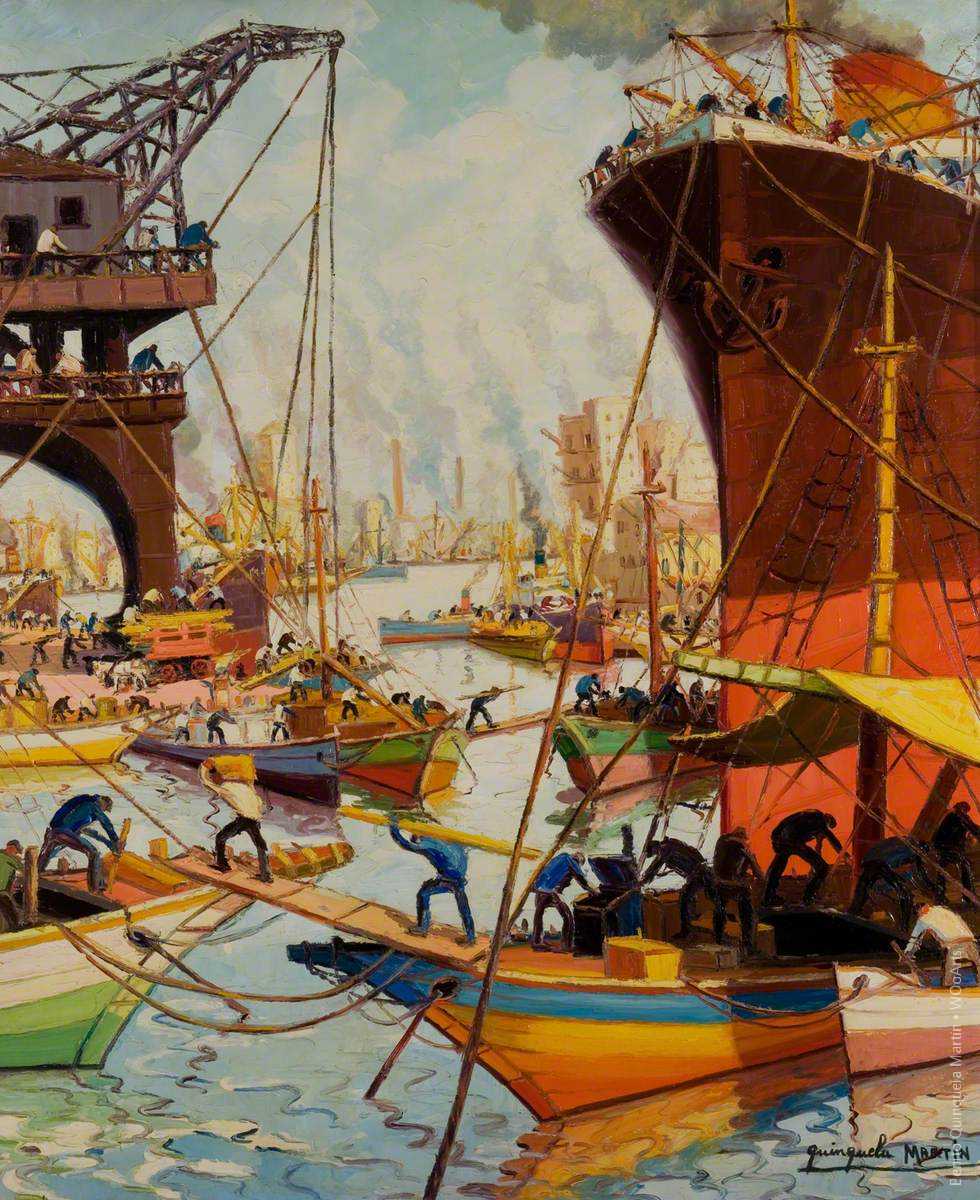

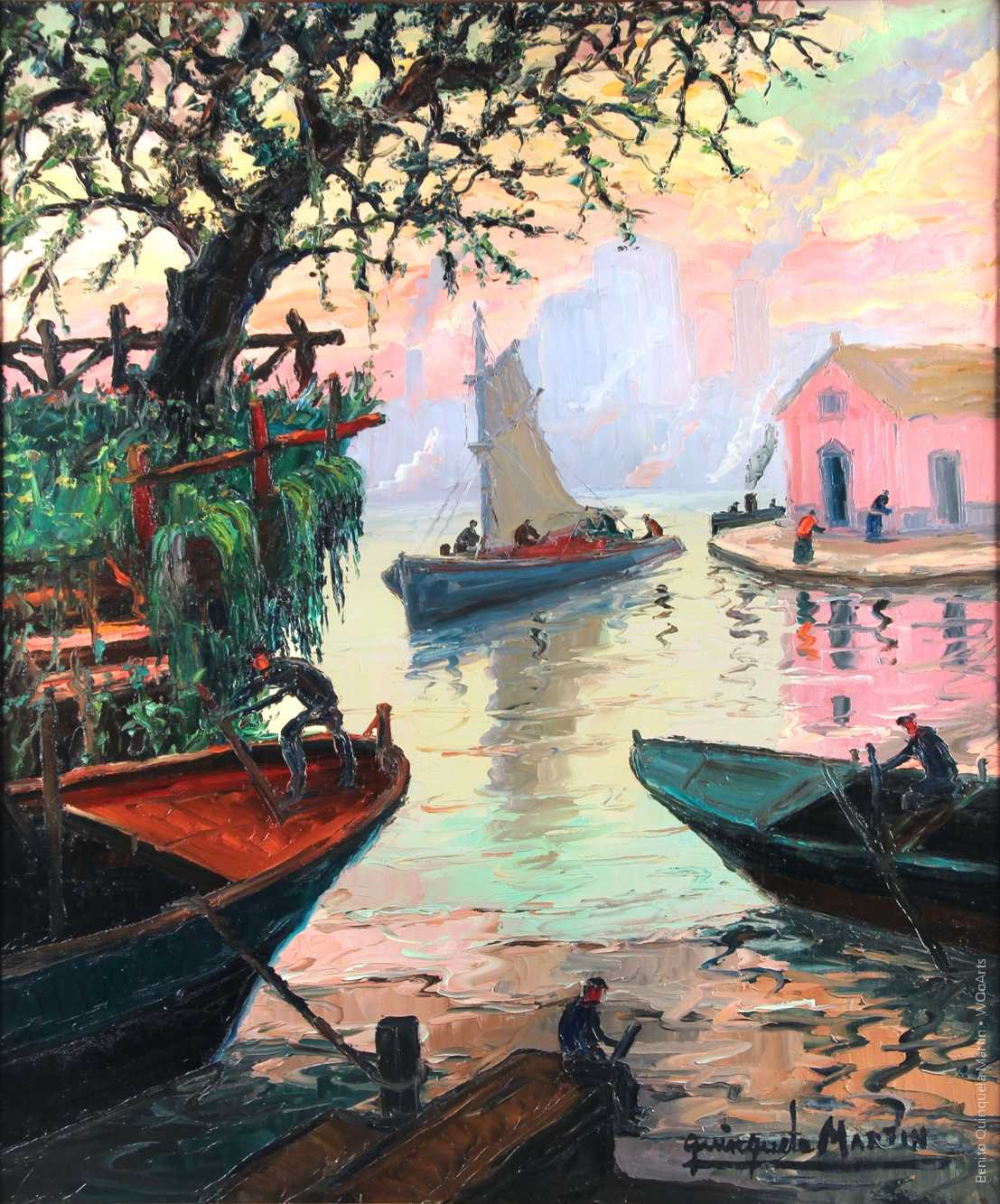

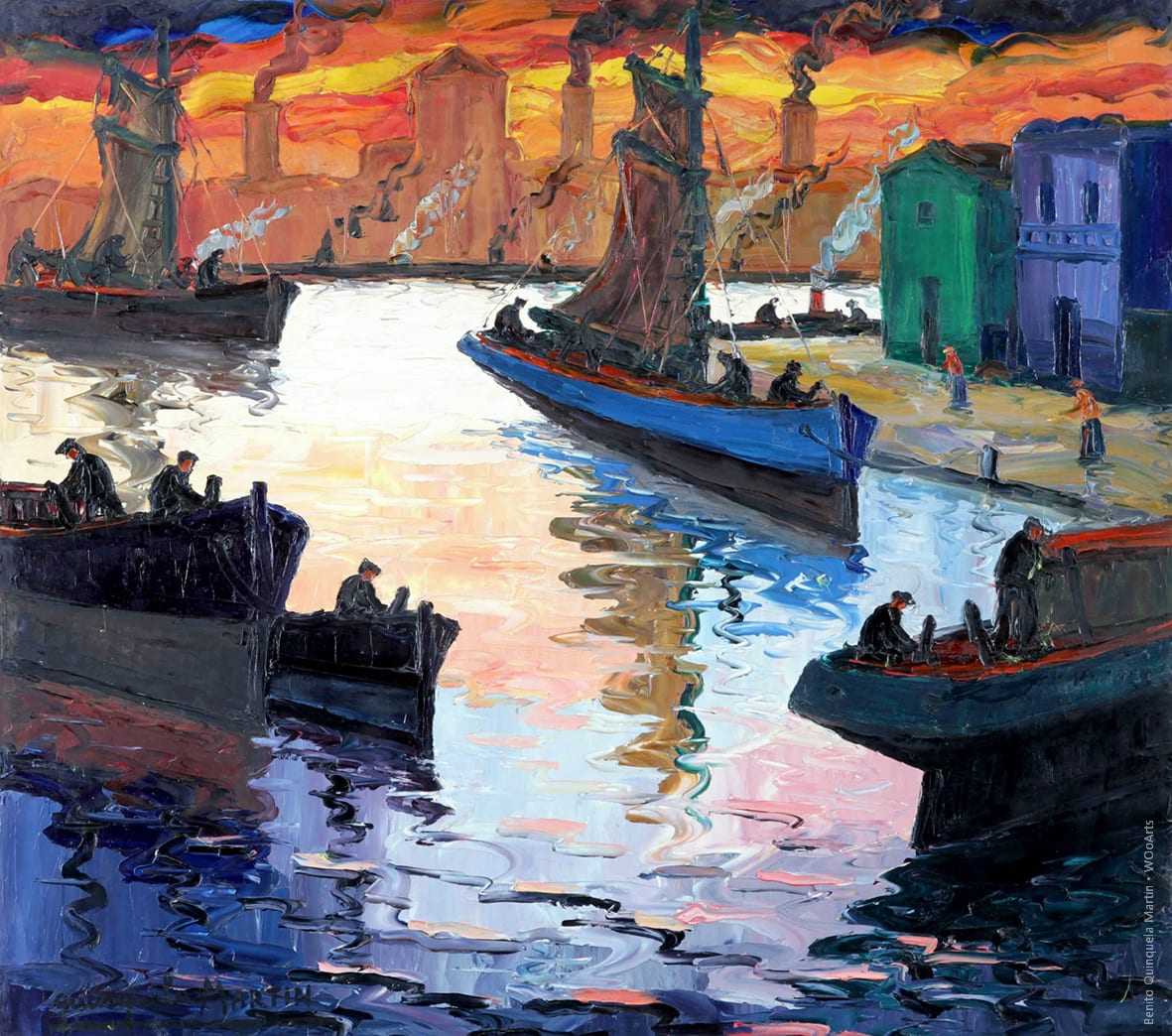

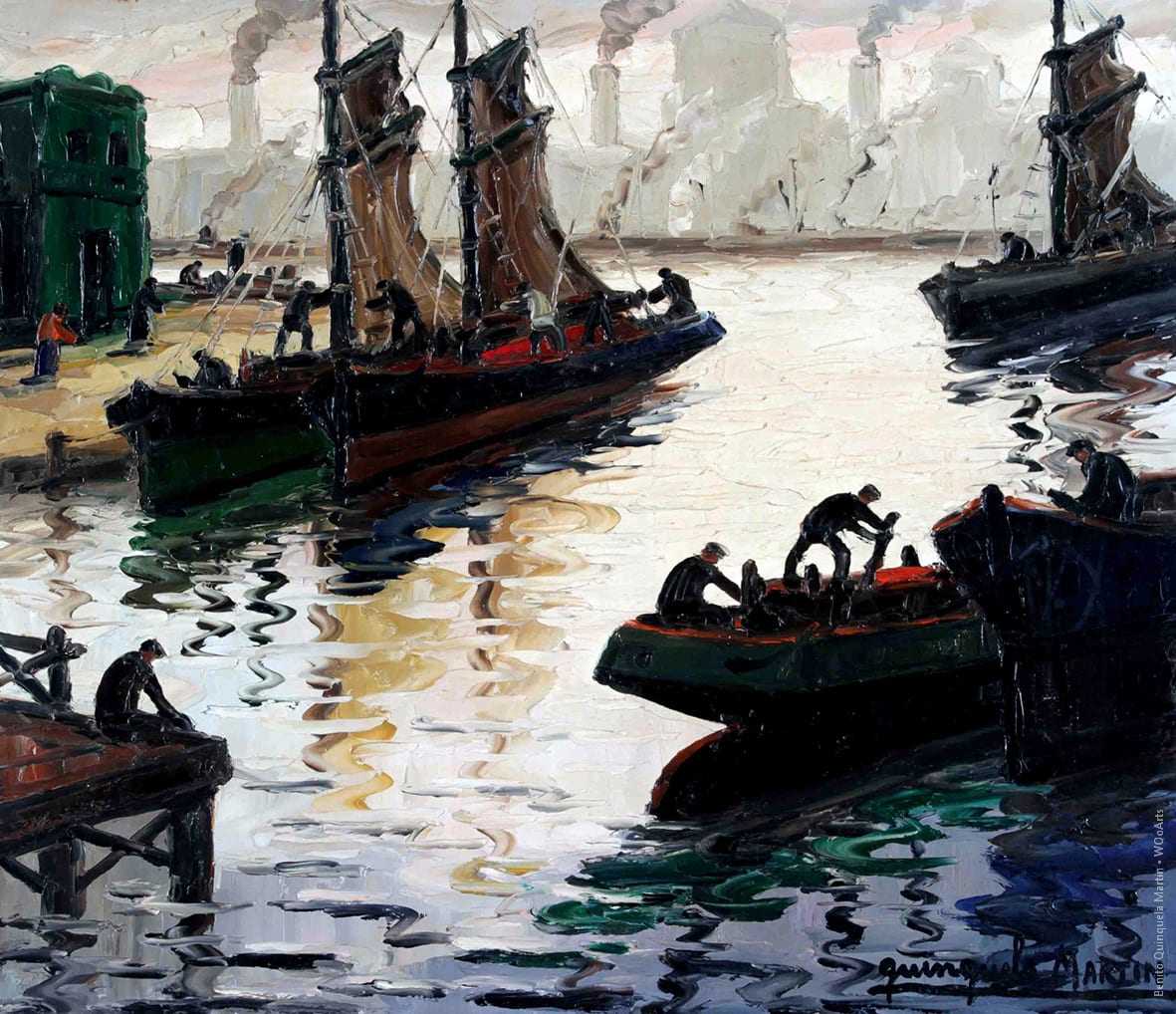

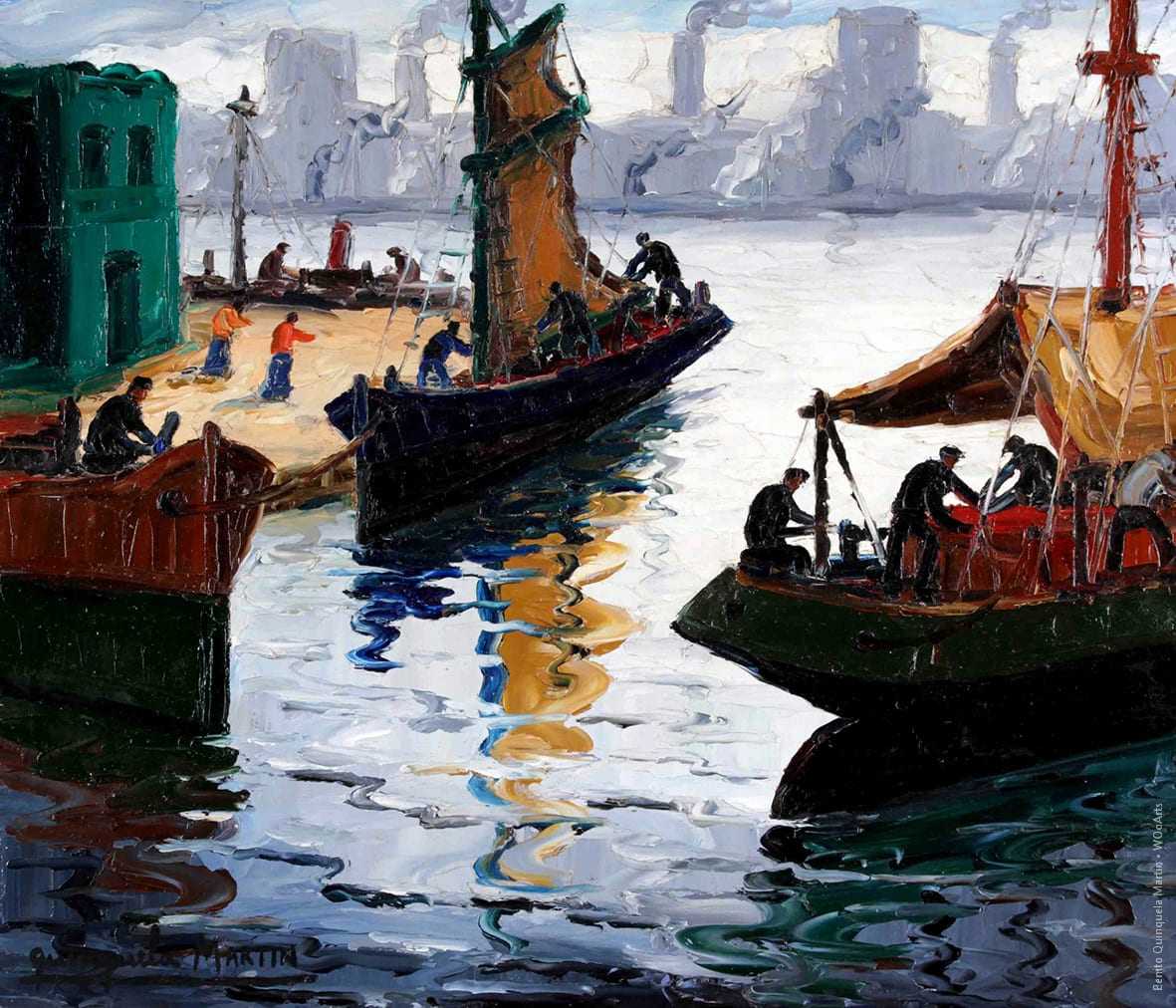

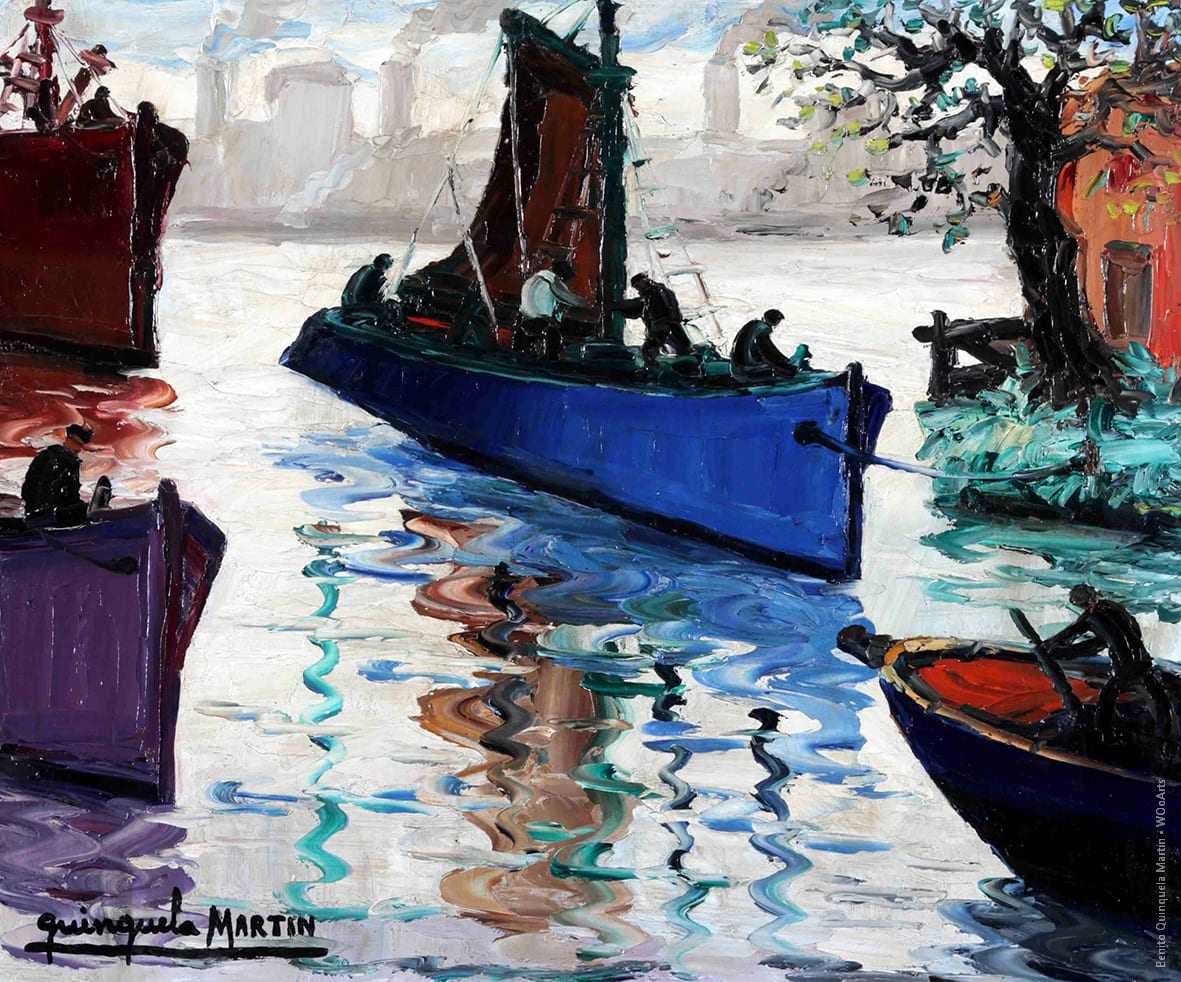

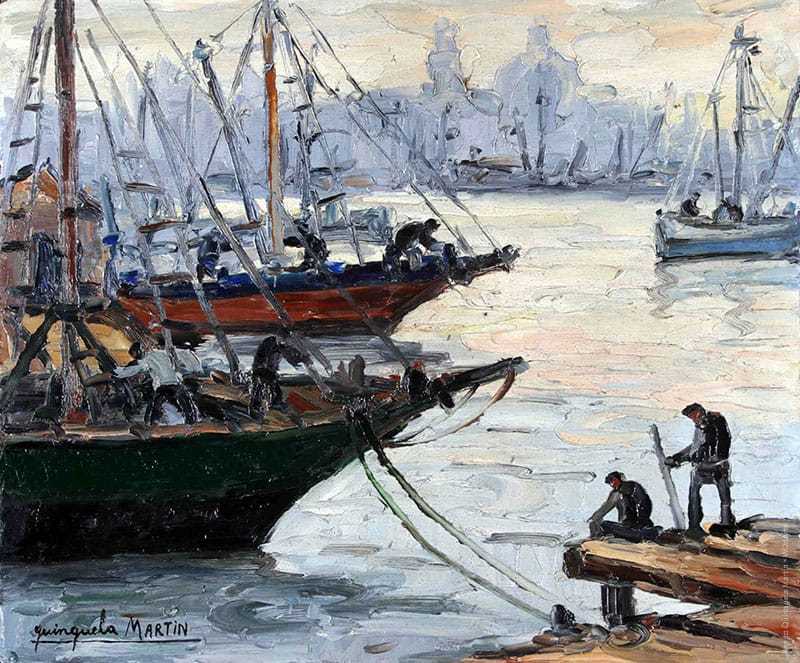

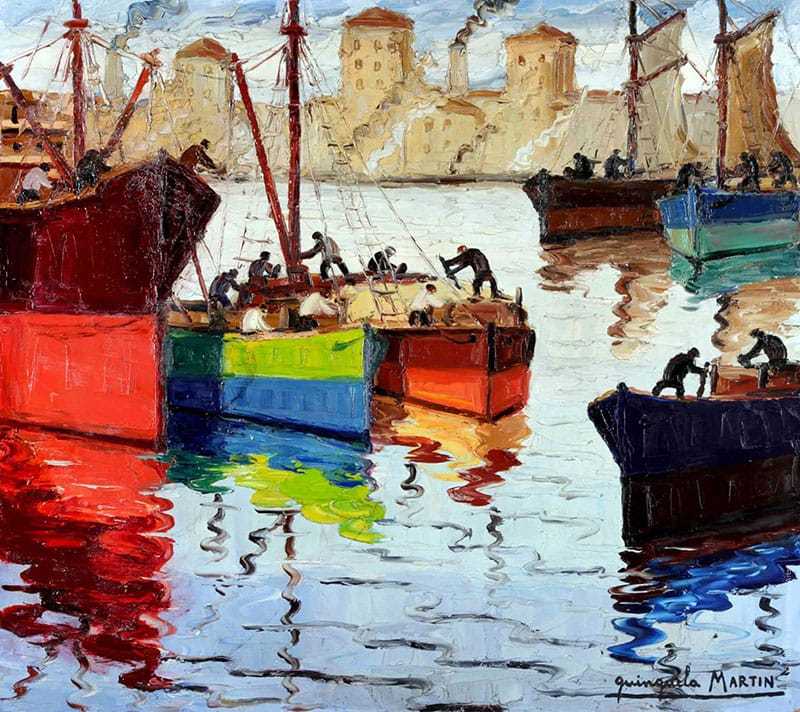

The Palette: Quinquela Martín’s art is characterized by a rich and vibrant palette that captures the essence of the La Boca neighborhood. The use of bold and contrasting colors, such as fiery reds, deep blues, and sunny yellows, imparts a sense of vitality to his paintings. The artist’s choice of hues reflects the energetic spirit and dynamic nature of the bustling port district.

- Bold and contrasting colors infuse vitality into Quinquela Martín’s works.

- The palette mirrors the energetic spirit of La Boca.

Composition and Perspective: One of the defining features of Quinquela Martín’s art is his adept use of composition and perspective. His works often portray scenes from unique angles, providing viewers with a fresh and immersive experience. The artist’s mastery of perspective creates a sense of depth, drawing the audience into the heart of the bustling La Boca streets.

- Unique perspectives offer a fresh and immersive viewing experience.

- Mastery of perspective creates a sense of depth in his works.

Human Element: Quinquela Martín’s art is not just a portrayal of landscapes but a celebration of the human spirit. His paintings are populated with characters engaged in various activities, providing a glimpse into the daily life of La Boca. The artist’s ability to capture the expressions, emotions, and gestures of the people adds a human touch to his vibrant canvases.

- The human element adds a personal touch to Quinquela Martín’s art.

- Expressive characters bring the paintings to life.

Symbolism and Social Commentary: Beyond the surface, Quinquela Martín’s art carries layers of symbolism and social commentary. His depictions of the port, ships, and industrial elements are not merely representational but convey deeper meanings about the socio-economic conditions of La Boca. The artist’s keen observation and ability to infuse his works with subtle commentary elevate his art to a realm of social significance.

- Symbolism adds depth and complexity to Quinquela Martín’s art.

- Social commentary provides insight into the artist’s perspective.

Benito Quinquela Martín, el creador de La Boca

Who was Benito Quinquela Martín and how did he become one of the greats of Argentine culture? Víctor Fernández, director of the “Benito Quinquela Martín” Museum of Fine Arts, tells of the artist and the setting of the work where he carried out his work, the effort, and observed the transformation of human work.Other articles that may interest youFernando Fader, brushstrokes of an Argentine life 85 years after the painter’s death, we remember and celebrate his work: one of the most important and loved by collectors of Argentine art, and one of the few who knew how to portray, in an intimate and personal way, the atmosphere of the landscapes of our land. .

On January 28, 1977, the plastic artist Benito Quinquela Martín died , considered by himself as “the inventor of La Boca . ” He was 87 years old and had a collection of paintings that were invaluable to Argentine culture. Víctor Fernández, director of the “Benito Quinquela Martín” Museum of Fine Arts, tells us the most unknown anecdotes about him and retraces the steps that the painter himself took in life.

The life of Benito Quinquela Martín is a legend. He was abandoned on March 21, 1890 in the House of Foundlings , Casa Cuna, and there the date of his birth was established by approximation: March 1. That day he would celebrate his birthday until the end of his existence. In that orphanage he would live his early childhood.

At the age of eight , the Chinchella couple came into his life . Her adoptive father, Manuel, was Genoese and raised in Olavarría. His adoptive mother, Justina Molina, from Entre Ríos, from Gualeguaychú and of indigenous descent. They had a very modest coal factory.

Benito attended two years of primary school and began working as a collaborator in the coal factory. As a teenager he helped his father in the port, as a stevedore. ” The dockworkers were the omnipresent subject in his painting of him, a universe that he knew deep inside, what was the hope of work and also the hard suffering that it meant ,” explains Víctor Fernández.

In love with La Boca

The neighborhood of La Boca meant a special dazzle for Benito. La Boca was a babel, not only because of the mixture of languages, but because of the multiplicity of cultures. There were Italians, Japanese, Chinese, Uruguayans, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Turks, blacks.

That incessant bustle of work at the port, a landscape that was unlike any other in the city of Buenos Aires, the landscape of the river, the wildest environments of Maciel Island and some parts of La Boca, the architecture of Boca, the color of that architecture, originated the eternal romance between La Boca and Quinquela.

His beginnings in art

In that diverse neighborhood, culture was part of daily life. The presence of artisans, carvers and sculptors was natural. The exercise of art was an everyday thing. Benito, while he divided his time between the coalyard and work in the port, scribbled and rehearsed some drawings with the coal from the coalyard, as he himself admitted, “with an encyclopedic ignorance . ”

The first brush he took in his life was at the age of 14, in 1904, when he participated to earn a few pesos in the campaign that led Alfredo Palacios to be the first socialist deputy in Latin America.

His vocation was affirmed with entry to the Pezzini-Stiatessi academy , one of the many proletarian institutions in the neighborhood. Various disciplines were taught there, including drawing and painting, and there he adopted the only teacher he would have in life: Alfredo Lázari. With him begins the definitive orientation of Quinquela’s vocation.

Your inspiration

His inspiring muse was a place. “La Boca, its people, the daily pulse of the neighborhood’s streets were that inspiring muse ,” describes the Museum Director. And he adds: “When he affirms his vocation and his language, when he begins to be Quinquela, he will adopt a theme, a repertoire, an iconography that will be self-imposed as his brand and he will feel unable to paint anything other than La Mouth” .

“Quinquela’s paintings are not landscapes but scenarios. The scene of work, of effort, of the transformation of human work. El Riachuelo is the trigger for that great work that results in thriving cities, in dreams of progress.”

Fictions of La Boca

According to Víctor Fernández it is very difficult to find objects or places directly referenced in his work. “His paintings of him reflect a total perception of the neighborhood ,” he explains. “Quinquela mixes in the paintings things that he had seen or had been told, things from his past, records of what he saw through the window, as well as things that never existed in the neighborhood but that prefigured what he thought was going to happen. be the future in the area” .

“The Mouth that he creates in his paintings is a great fiction, a great invention, with such power, with such authenticity that it makes us all convinced that La Boca was really the way he painted it. He is going to transform it like he did.” He wanted it to be, with those great urban interventions such as the painting of the cranes, of the winches, of the streets, the great creation of the landscape that is Caminito Street. He expressed “La Boca is an invention of mine”, an invention that took root very deeply, in an absolute knowledge of the cultural roots of their neighborhood.

How is Quinquela Martin’s work divided?

His work is divided into large series: Bright Days, Gray Days, Fire series and Ship Cemeteries. In all of them the Boca landscape will appear in some way and when it moves too far from reality it puts a “real” element on the horizon to put us back in the neighborhood: the dome of the San Juan Evangelista church, some detail of the Transborador Bridge , the old Pueyrredón de Barracas Bridge.

The techniqueThe director of the Museum describes that the artist has an absolutely original brand, his own language and technique, and that his great virtue is based on representation through matter.

“Not only a use of color, which distanced it from many academic precepts, causing a rejection by the elites of educated Buenos Aires critics, but its representation will be based on the use of thick layers of matter that took up what was the volume of the object represented. The oil paint applied with a spatula emphasizes those directions and those volumes. He himself described his work saying that “for a very large work it could take a day of work, after having macerated it in his soul for several months.” .

A colorful death

The remains of Benito Quinquela Martín were buried in a coffin made by him , years before, because he said “that someone who lived surrounded by color cannot be buried in a smooth box . ” A scene of the port of La Boca was painted on the wood that made up the coffin.

Benito Quinquela Martín had a very hard life of effort and work. Even when he dedicated himself to art, he never stopped feeling like just another worker and he never took away the effort that art demanded throughout his life.He died on January 28, 1977.

Source: Ministero de Cultura Argentina