Paul Klee was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism.

Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented with and eventually deeply explored color theory, writing about it extensively; his lectures Writings on Form and Design Theory, published in English as the Paul Klee Notebooks, are held to be as important for modern art as Leonardo da Vinci’s A Treatise on Painting for the Renaissance.

He and his colleague, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, both taught at the Bauhaus school of art, design and architecture in Germany. His works reflect his dry humor and his sometimes childlike perspective, his personal moods and beliefs, and his musicality.

A Swiss-born painter and graphic artist whose personal, often gently humorous works are replete with allusions to dreams, music, and poetry, Paul Klee is difficult to classify. Primitive art, surrealism, cubism, and children’s art all seem blended into his small-scale, delicate paintings, watercolors, and drawings.

Klee grew up in a musical family and was himself a violinist. After much hesitation he chose to study art, not music, and he attended the Munich Academy in 1900. There his teacher was the popular symbolist and society painter Franz von Stuck. Klee later toured Italy (1901-02), responding enthusiastically to Early Christian and Byzantine art.

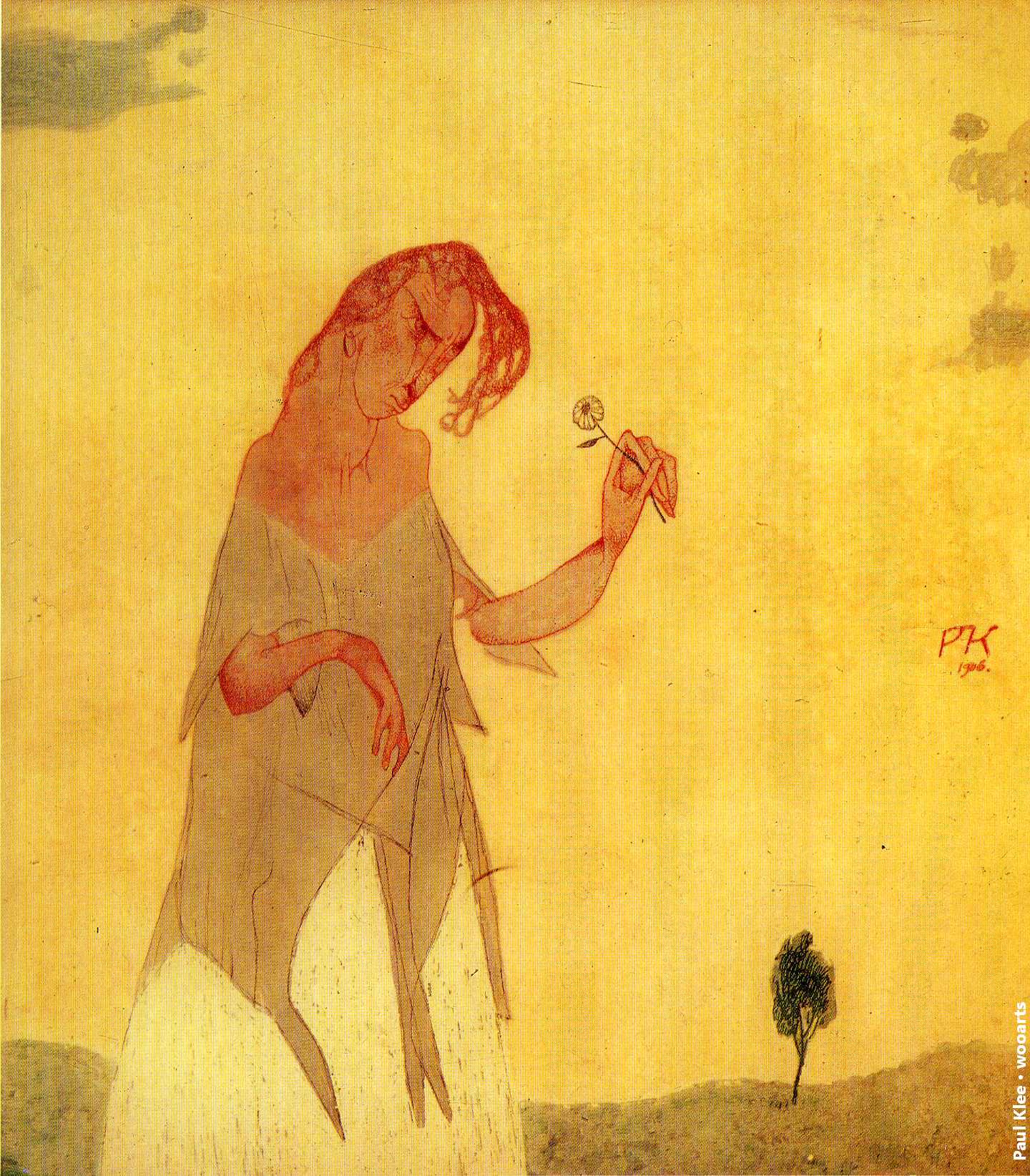

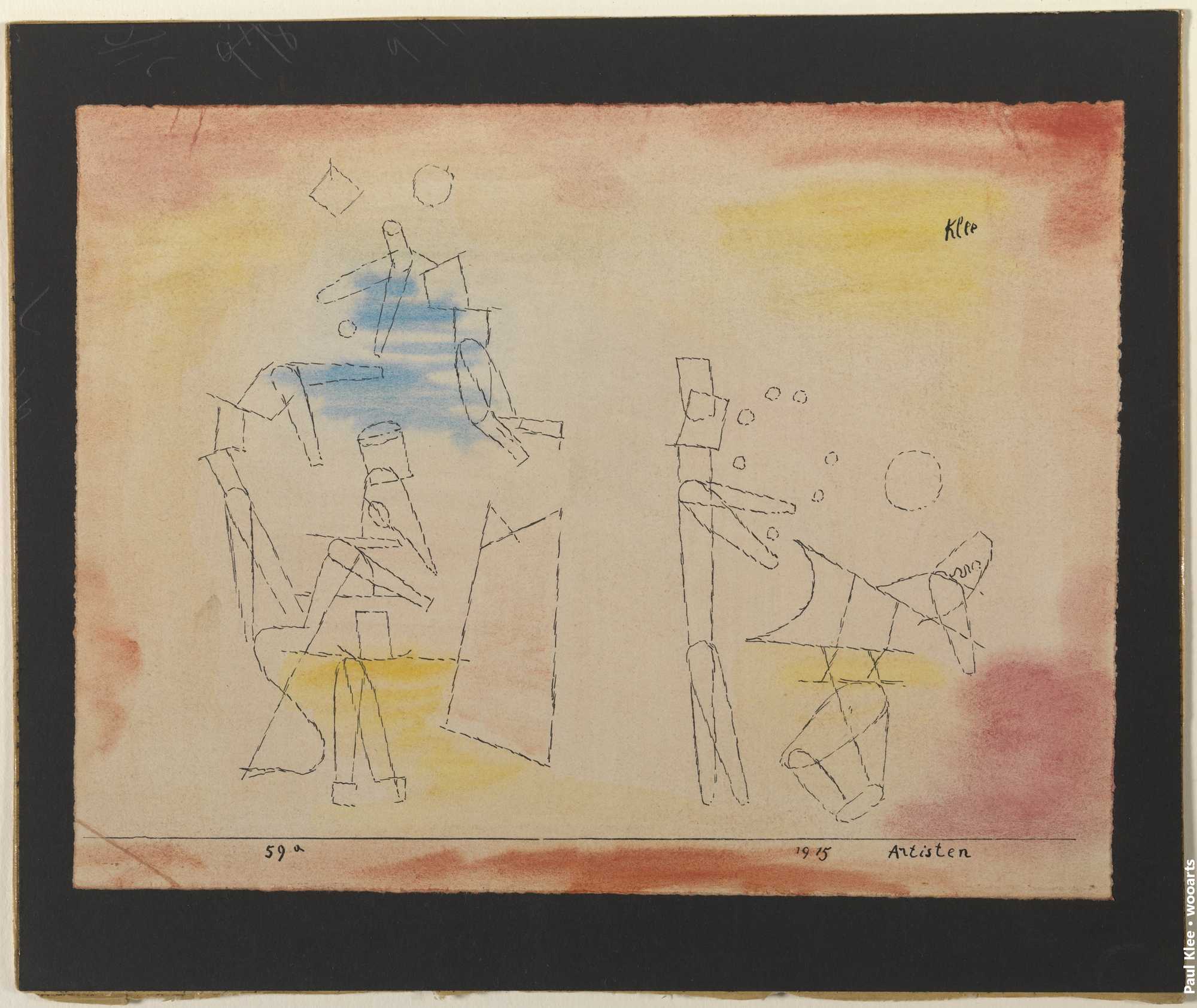

Klee’s early works are mostly etchings and pen-and-ink drawings. These combine satirical, grotesque, and surreal elements and reveal the influence of Francisco de Goya and James Ensor, both of whom Klee admired. Two of his best-known etchings, dating from 1903, are Virgin in a Tree and Two Men Meet, Each Believing the Other to Be of Higher Rank. Such peculiar, evocative titles are characteristic of Klee and give his works an added dimension of meaning.

After his marriage in 1906 to the pianist Lili Stumpf, Klee settled in Munich, then an important center for avant-garde art. That same year he exhibited his etchings for the first time. His friendship with the painters Wassily Kandinsky and August Macke prompted him to join Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), an expressionist group that contributed much to the development of abstract art. A turning point in Klee’s career was his visit to Tunisia with Macke and Louis Molliet in 1914.

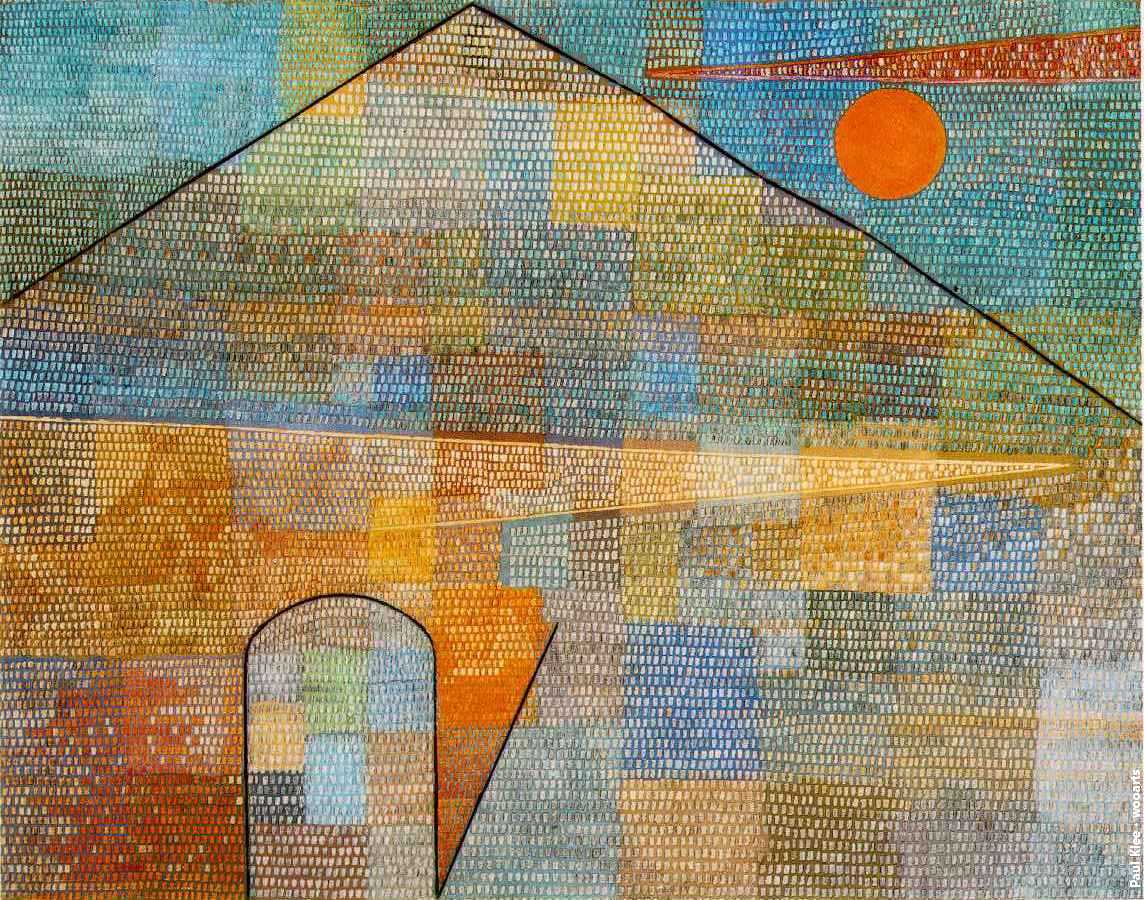

He was so overwhelmed by the intense light there that he wrote: “Color has taken possession of me; no longer do I have to chase after it, I know that it has hold of me forever. That is the significance of this blessed moment. Color and I are one. I am a painter.” He now built up compositions of colored squares that have the radiance of the mosaics he saw on his Italian sojourn. The watercolor Red and White Domes (1914; Collection of Clifford Odets, New York City) is distinctive of this period.

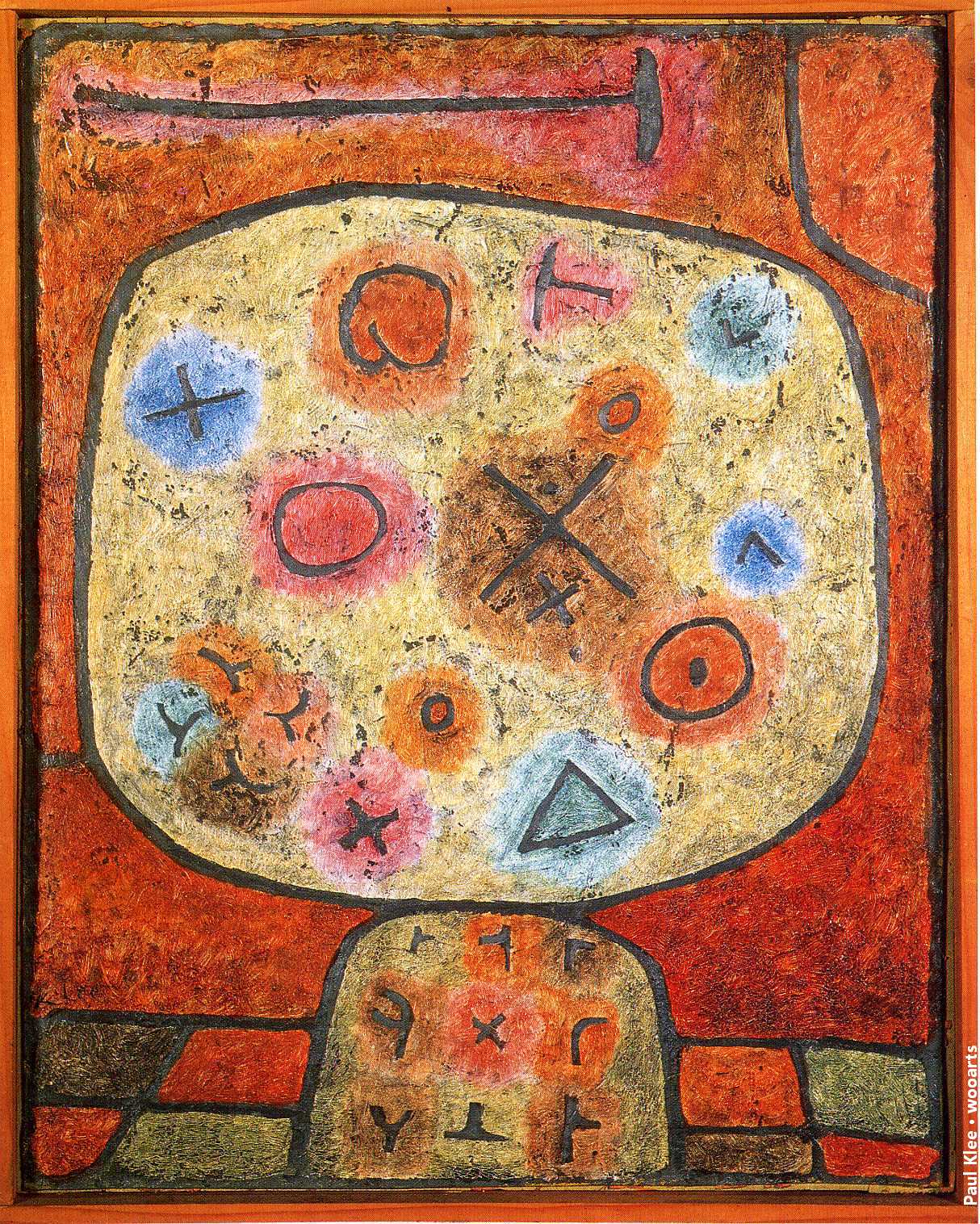

Klee often incorporated letters and numerals into his paintings, as in Once Emerged from the Gray of Night (1917-18; Klee Foundation, Berlin). These, part of Klee’s complex language of symbols and signs, are drawn from the unconscious and used to obtain a poetic amalgam of abstraction and reality. He wrote that “Art does not reproduce the visible, it makes visible,” and he pursued this goal in a wide range of media using an amazingly inventive battery of techniques. Line and color predominate with Klee, but he also produced series of works that explore mosaic and other effects.

Klee taught at the Bauhaus school after World War I, where his friend Kandinsky was also a faculty member. In Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925), one of his several important essays on art theory, Klee tried to define and analyze the primary visual elements and the ways in which they could be applied. In 1931 he began teaching at Dusseldorf Akademie, but he was dismissed by the Nazis, who termed his work “degenerate.” In 1933, Klee went to Switzerland.

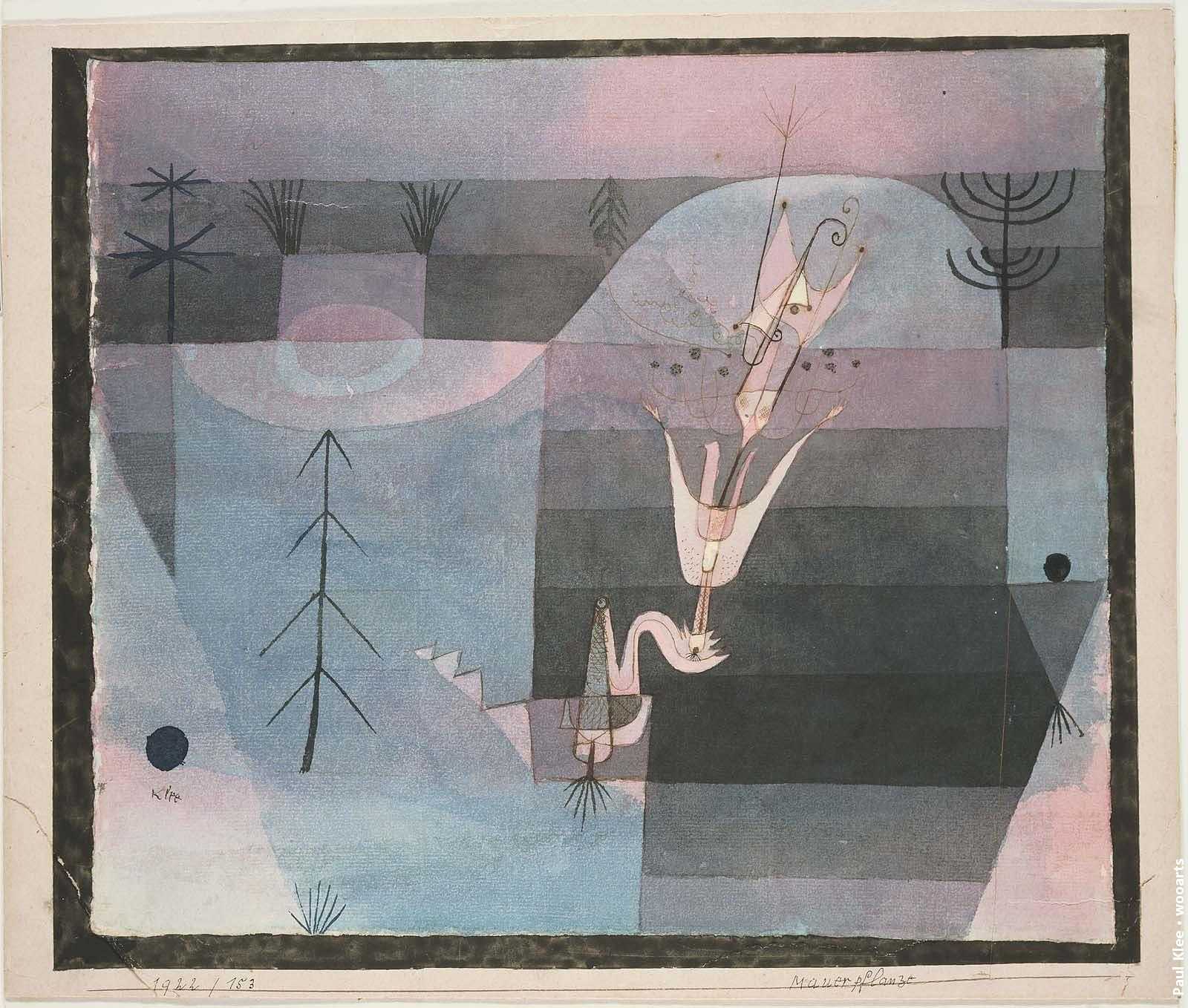

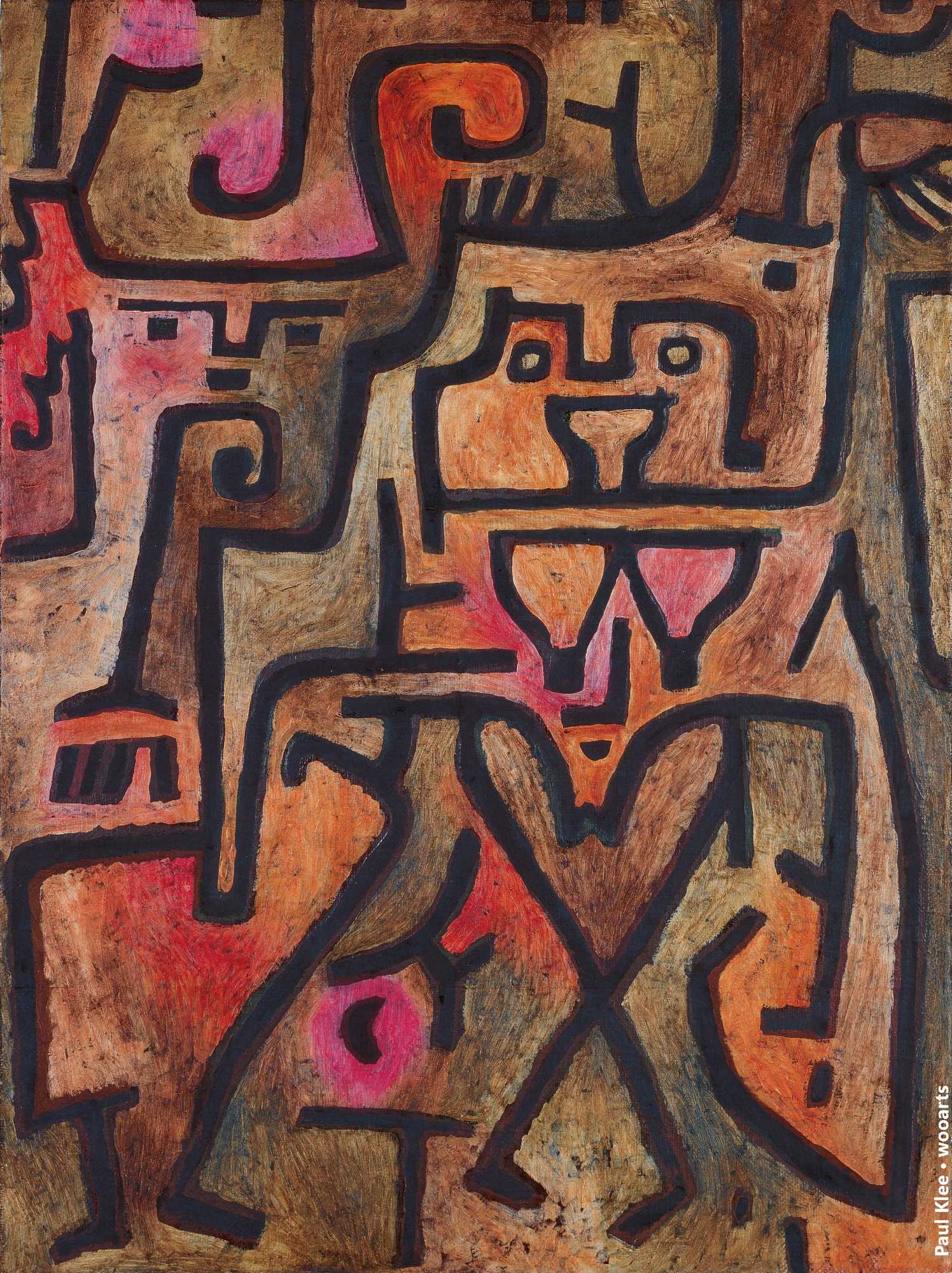

There he came down with the crippling collagen disease scleroderma, which forced him to develop a simpler style and eventually killed him. The late works, characterized by heavy black lines, are often reflections on death and war, but his last painting, Still Life (1940; Felix Klee collection, Bern), is a serene summation of his life’s concerns as a creator.

—

Paul Klee was one of the great masters who established the essence and character of modern art. He was an artist of a creative capacity and an artistic range and depth that had not existed in German countries since Albrecht Durer’s time. Like Durer, Klee was predominantly a draftsman. Color entered his art late, and the main body of his work was always dominated by the linear component. His fantasy seemed inexhaustible–the demonic bordering on the grotesque, the humorous on the anecdotal–but it was always rooted in his metaphysical, even mystical, attitude to life and art. Klee was also an outstanding writer on formal and esthetic problems and a distinguished teacher. To him we owe some of the most beautiful statements on modern art.

Paul Klee (1879–1940)

Sabine Rewald

Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

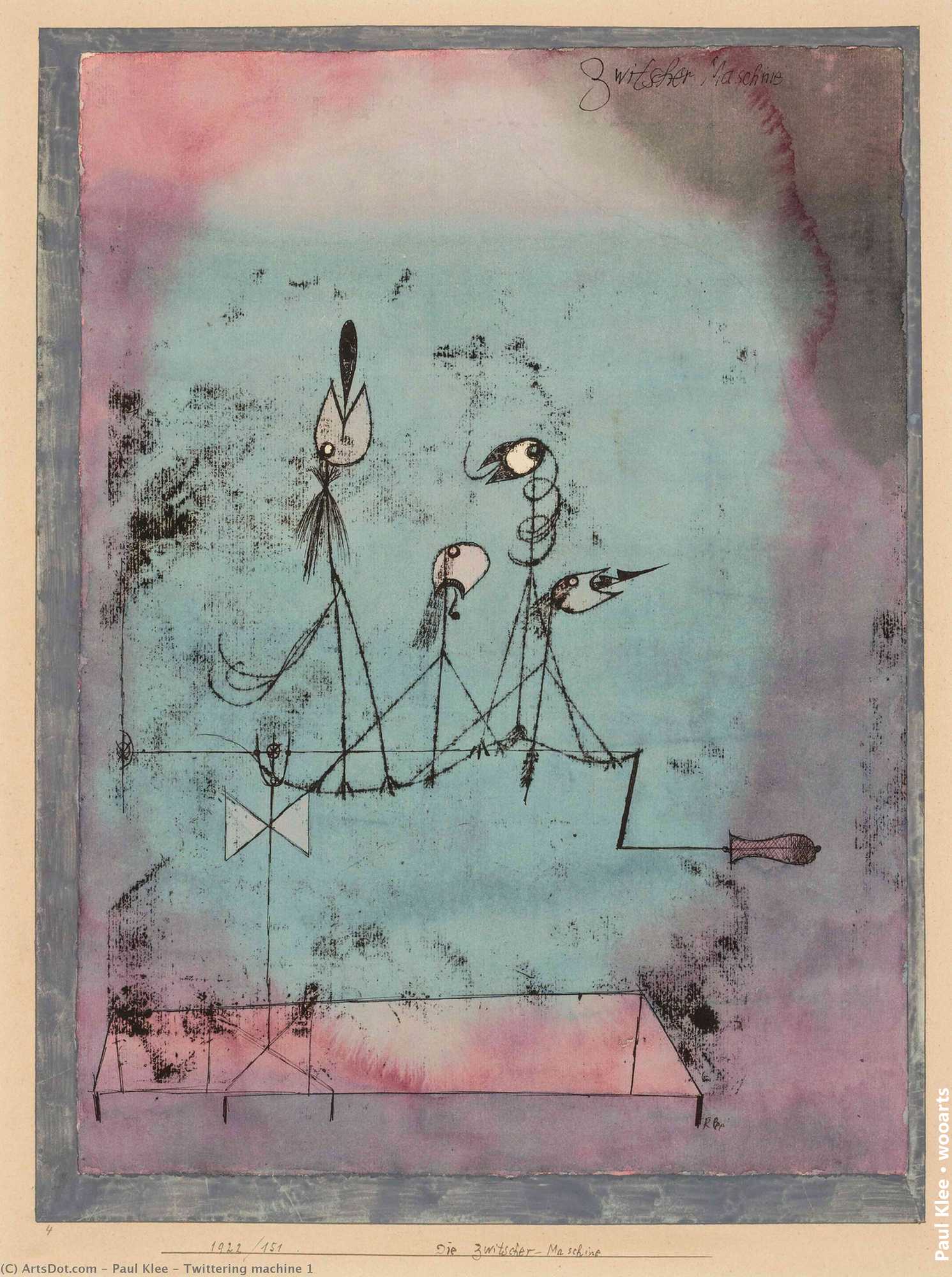

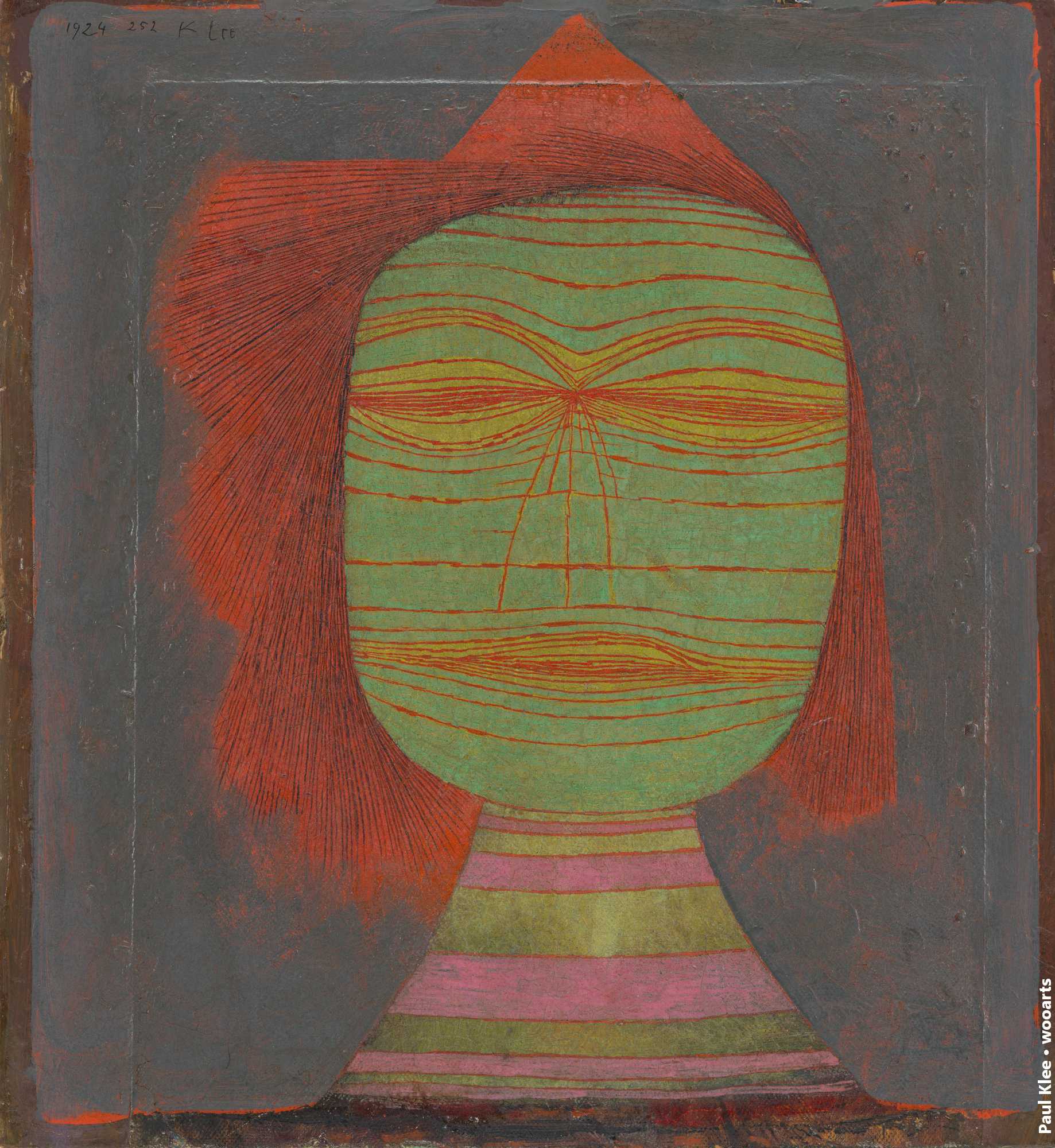

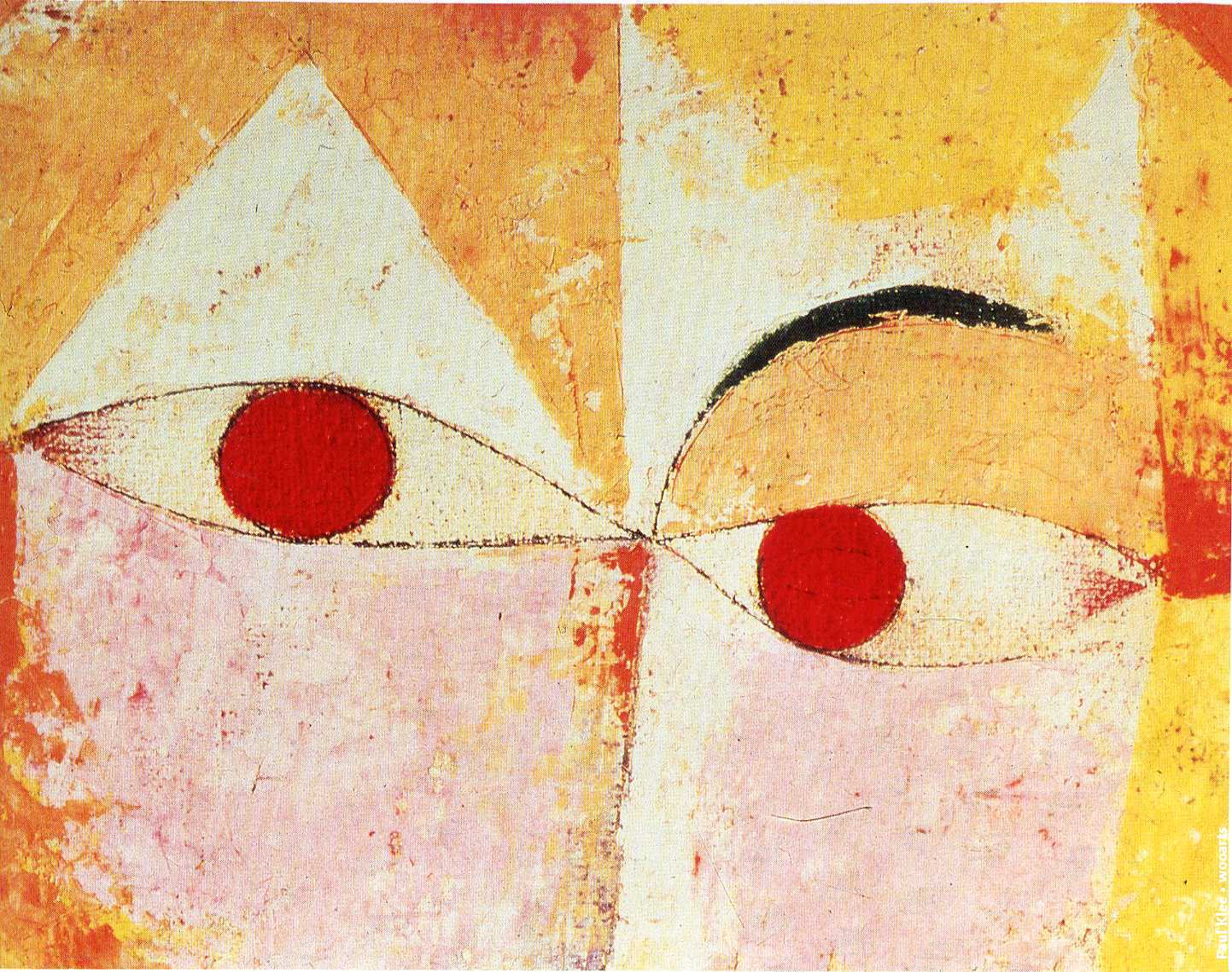

With Heinz Berggruen’s gift of ninety works by Paul Klee spanning the artist’s entire career, the Metropolitan Museum has become an important center for the study of this German artist. Klee is known for his simple stick figures, suspended fish, moon faces, eyes, arrows, and quilts of color, which he orchestrated into fantastic and childlike yet deeply meditative works.

Klee was born in 1879 in Münchenbuchsee, near Bern, Switzerland, the second child of Hans Klee, a German music teacher, and a Swiss mother. His training as a painter began in 1898 when he studied drawing and painting in Munich for three years. By 1911, he had returned to that city, where he became involved with the German Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), founded by Vasily Kandinsky and Franz Marc in 1911. Klee and Kandinsky became lifelong friends, and the support of the older painter provided much-needed encouragement. Until then, Klee had worked in relative isolation, experimenting with various styles and media, such as making caricatures and Symbolist drawings, and later producing small works on paper mainly in black and white. His work was also influenced by the Cubism of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and the abstract translucent color planes of Robert Delaunay.

In 1914, Klee visited Tunisia. The experience was the turning point in his life and career. The limpid light of North Africa awakened his sense of color. During his stay, Klee gradually detached color from physical description and used it independently, which gave him the final needed push toward abstraction. The view of the mosque in Hammamet with Its Mosque (1914; 1984.315.4) demonstrates Klee’s path toward abstraction. By 1915, he had turned his back to nature and never again painted after the model. With abstracted forms and merry symbols, he expressed the most diverse subjects drawn from his imagination (1984.315.23), poetry, music (1984.315.36), literature (1984.315.26), and his reaction to the world around him (1987.455.1). His subjects reveal his impish humor (1987.455.7) and his bent toward the fantastic (1987.455.16) and the meditative (1984.315.54). Always preoccupied with the ring of words, titles played a major part in his work. Whether ironic, poetic, irreverent, deadpan, flippant, or—near the end of his life—melancholic, his titles set up the perspectives from which he wanted the works to be seen.

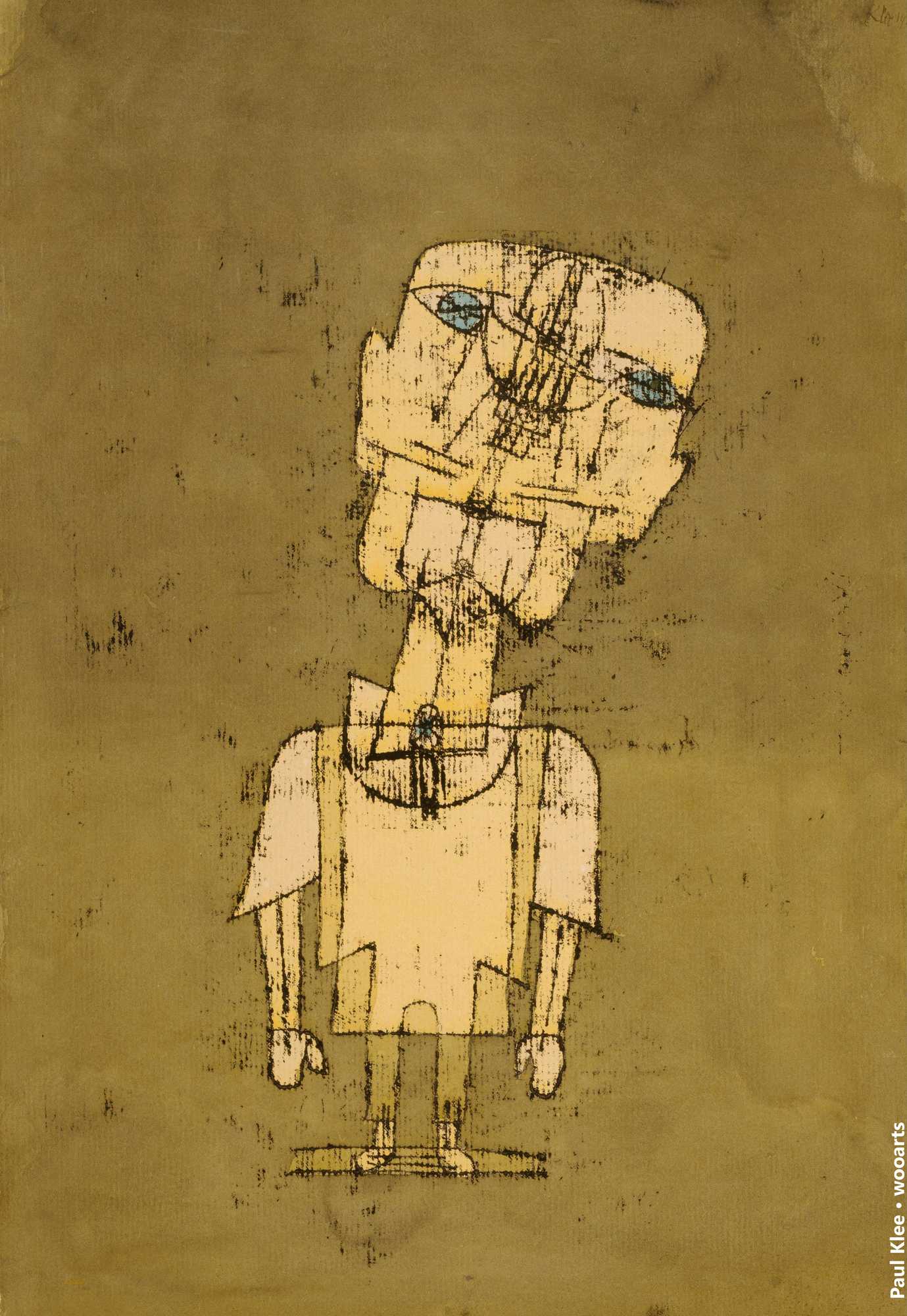

In 1920, Walter Gropius invited Klee to join the faculty of the Bauhaus. A school of architecture and industrial design operating first in Weimar (1919–25) and then Dessau (1925–32), it also included the study of arts and crafts. Nearly half of Klee’s some 10,000 works (mainly small-scale watercolors and drawings on paper) were produced during the ten years he taught at the Bauhaus, and they vary widely. Some relate to the subject of his courses, to his preoccupation with the relationship of colors, such as Static-Dynamic Gradation, produced in 1923 (1987.455.12). In the same year, Klee painted Ventriloquist and Crier in the Moor (1984.315.35), which, with its humor and grotesque fantasy, may strike many viewers as the quintessential “Klee.”

From 1931 to December 1933, Klee taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf. When the National Socialists declared his art “degenerate” in 1933, Klee returned to his native Bern. Personal hardship and the increasing gravity of the political situation in Europe are reflected in the somber tone of his late work. Lines turn into black bars, forms become broad and generalized, scale larger, and colors simpler, as in Comedians’ Handbill (1938; 1984.315.57) or Angel Applicant (1939; 1984.315.60).

via: metmuseum.org