the-national-memorial-for-peace-and-justice-002

Background

The memorial was built on six acres in the downtown area of the state capital by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit based in Montgomery. The related Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration opened the same day. The complex was built near the former market site in Montgomery where enslaved African Americans were sold. The development and construction of the memorial complex cost an estimated $20 million, raised from private foundations. Bryan Stevenson, founder of the EJI, was inspired by the examples of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany, and the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa, to create a single memorial to victims of white supremacy in the United States.

Gallery

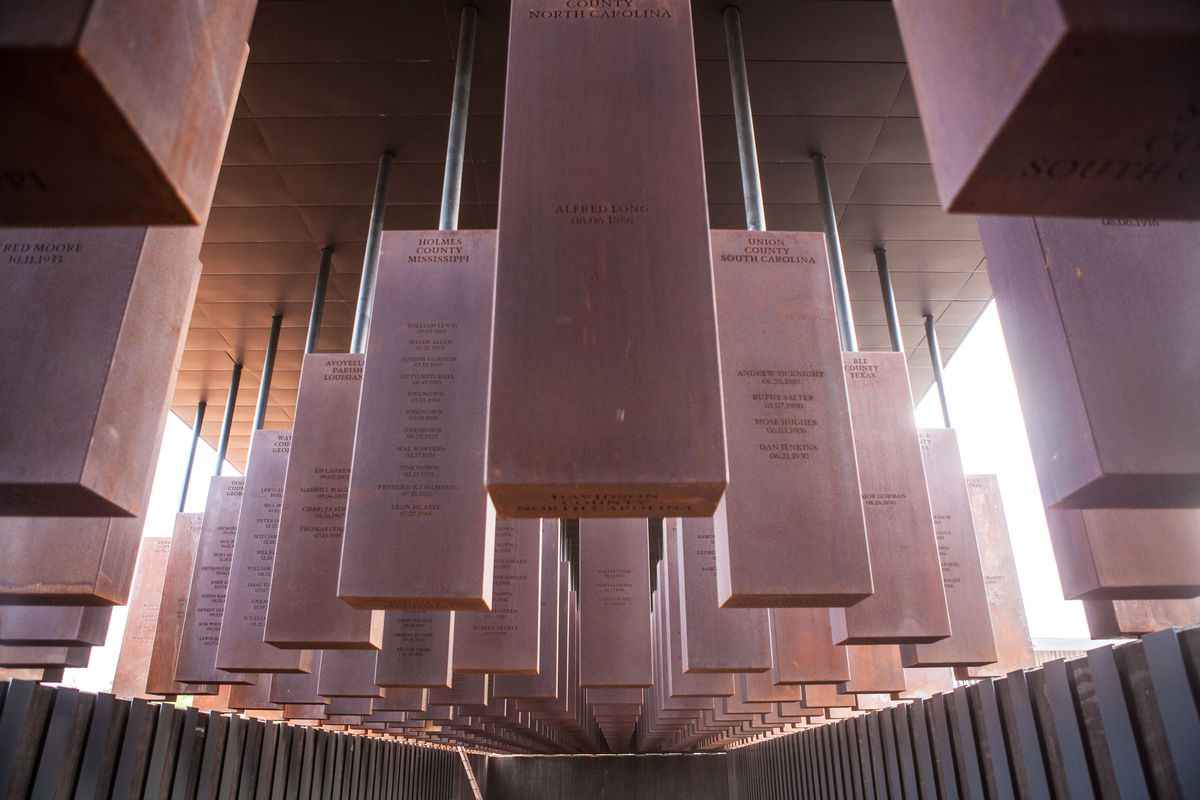

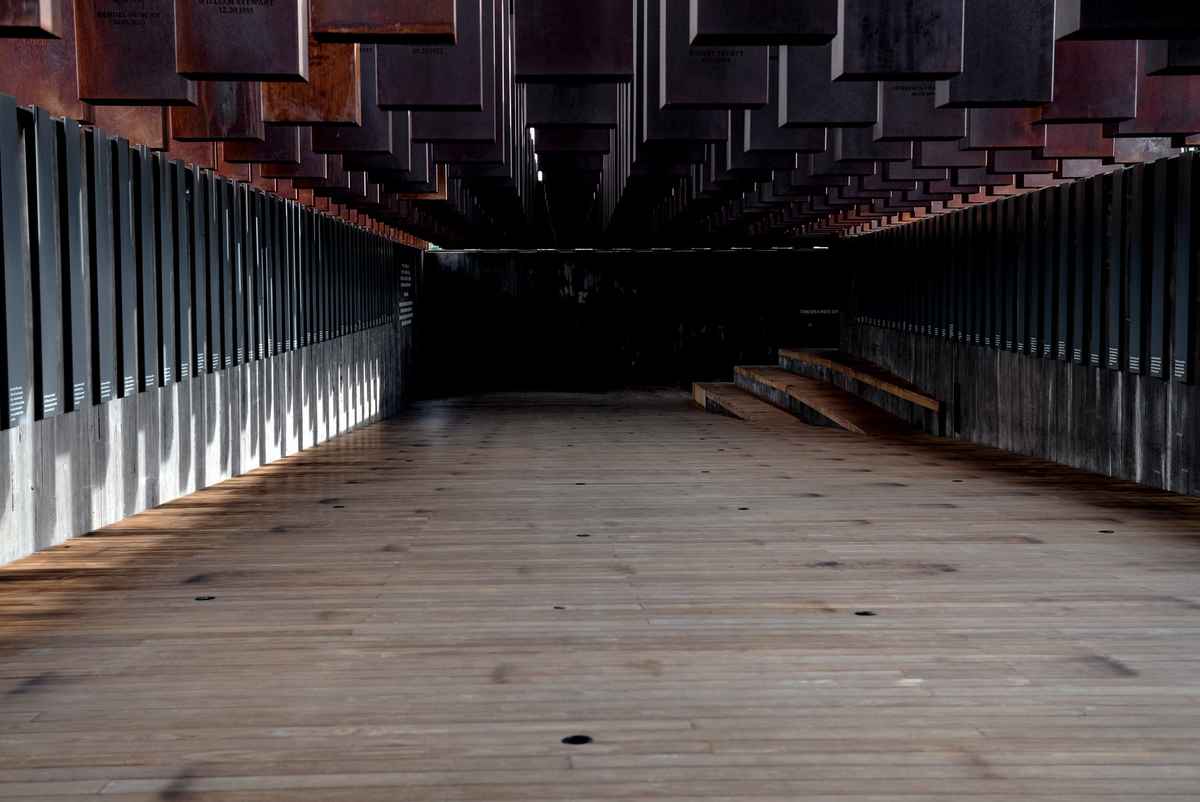

The pavilion floor slopes downward where the monuments are suspended, recalling the terrible fate of lynching victims.Credit...Johnathon Kelso for The New York Times

A 2010 sculpture by Titus Kaphar, “Doubt,” at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. The bronze figure has an oil painting in his grip.Credit...Johnathon Kelso for The New York Times

A sculpture by Hank Willis Thomas, “Raise Up,” on the grounds of the Memorial for Peace and Justice. Inspired by a 1960s photograph by Ernest Cole of South African miners, it suggests police suspects lined up at gunpoint.Credit...Johnathon Kelso for The New York Times

More than 800 stele-like, 6-foot-tall rusted steel mini-monuments represent the victims of lynching.Credit...Johnathon Kelso for The New York Times

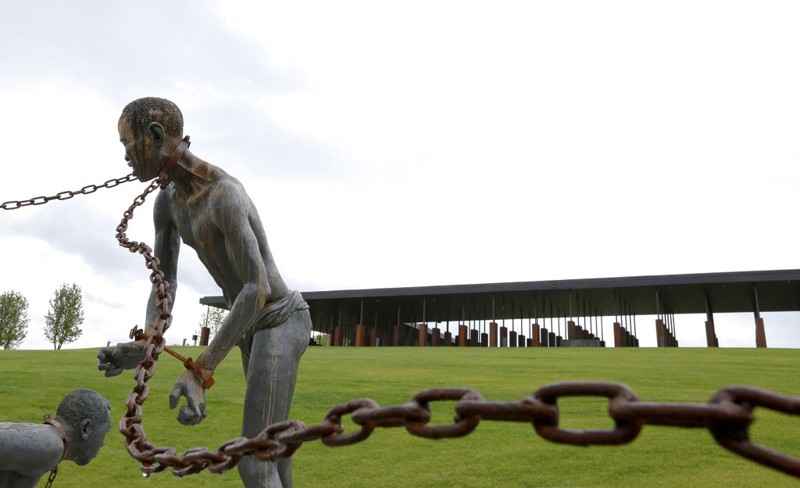

Brynn Anderson/APA statue depicting chained people on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a new memorial to honor thousands of people killed in racist lynchings, April 22, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala.A statue depicting chained people on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a new memorial to honor thousands of people killed in racist lynchings, April 22, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala.Brynn Anderson/AP

Mickey Welsh/Montgomery Advertiser via USA Today NetworkJars containing soil from the sites of confirmed lynchings in the state of Alabama are displayed at the Equal Justice Initiative offices, April 13, 2018; Montgomery, Ala.Jars containing soil from the sites of confirmed lynchings in the state of Alabama are displayed at the Equal Justice Initiative offices, April 13, 2018; Montgomery, Ala.Mickey Welsh/Montgomery Advertiser via USA Today Network

MONTGOMERY, AL - APRIL 26: Wretha Hudson, 73, discovers a marker commemorating lynchings in Lee County, Texas while visiting the National Memorial For Peace And Justice on April 26, 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama. Hudson, whose father's family came to Alabama from Lee County decades earlier, said the experience was overwhelming. 'It's a combination of pride and strength, for my people. In our culture, rain is a sign of acceptance from our ancestors. So the rain is a sign of their acceptance for this day.' The memorial is dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people and those terrorized by lynching and Jim Crow segregation in America. Conceived by the Equal Justice Initiative, the physical environment is intended to foster reflection on America's history of racial inequality. (Photo by Bob Miller/Getty Images)

MONTGOMERY, AL - APRIL 26: Markers display the names and locations of individuals killed by lynching at the National Memorial For Peace And Justice on April 26, 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial is dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people and those terrorized by lynching and Jim Crow segregation in America. Conceived by the Equal Justice Initiative, the physical environment is intended to foster reflection on America's history of racial inequality. (Photo by Bob Miller/Getty Images)

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is seen, it's a new memorial that is opening to honor thousands of people killed in racist lynchings on Monday, April 23, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala. The Memorial and Justice and the Legacy Museum will open on Thursday. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

This photo shows a bronze statue called 'Raise Up', part of the display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a new memorial to honor thousands of people killed in lynchings, Monday, April 23, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala. The memorial and an accompanying museum that open this week in Montgomery are a project of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative, a legal advocacy group in Montgomery. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

A statue of chained people is on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the new memorial is opening to honor thousands of people killed in racist lynchings on Sunday, April 22, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala. The Memorial and Justice and the Legacy Museum will open on Thursday. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

A statue of chained people is on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the new memorial is opening to honor thousands of people killed in racist lynchings on Sunday, April 22, 2018, in Montgomery, Ala. The Memorial and Justice and the Legacy Museum will open on Thursday. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

By studying records in counties across the United States, researchers documented almost 4400 “racial terror lynchings” in the post-Reconstruction era between 1877 and 1950. Most took place in the decades just before and after the turn of the 20th century. An error at the memorial in the name of a victim from Duluth, Minnesota, was quickly corrected.

Description

In the central position is the memorial square with 805 hanging steel rectangles, the size and shape of coffins. These name and represent each of the counties (and their states) where a documented lynching took place in the United States, as compiled in the EJI study, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (2017, 3rd edition). Each of the steel plates also has the names of the documented lynching victims (or “unknown” if the name is not known). The names and dates of documented victims are engraved on the panels. More than 4075 documented lynchings of African Americans took place between 1877 and 1950, concentrated in 12 Southern states. In addition, the EJI has published supplementary information about lynchings in several states outside the South. The monument is the first major work in the nation to name and honor these victims.

The central memorial was designed by MASS Design Group with Lam Partners lighting design, and built on land purchased by EJI. Hank Willis Thomas’s sculpture, Rise Up, features a wall, from which emerge statues of black heads and bodies raising their arms in surrender to the viewer. The piece suggests visibility, which is one of the intentions of the monument. The viewer is asked to focus and see the subject of the artwork. This is a more current piece commenting on the police violence and police brutality prevalent in the years preceding the memorial. Thomas has said about his artwork, “I see the work that I make as asking questions.”

In the landscaped area outside the monument are benches where visitors can sit to reflect. These are dedicated to commemorating such activists as journalist Ida B. Wells, who in the 1890s risked her life to report that lynchings were more about economic competition of blacks and whites, than actual assaults by blacks of whites. Laid in rows on the ground are steel columns corresponding to those hanging in the Memorial. These columns are intended to be temporary. The Equal Justice Initiative is asking representatives of each of the counties to claim their monument and establish a memorial on home ground to lynching victims, and to conduct related public education.

A month after the monument’s opening, the Montgomery Advertiser reported that citizens in Montgomery County were considering asking for their column. Both county and the city of Montgomery officials were also discussing this.

Importance for Montgomery tourism

Prior to the 1990s, there was limited acknowledgement in Montgomery to the painful legacy of slavery and racism, although the city had numerous monuments related to the Confederacy, many erected by private organizations. The city has developed a Civil Rights trail marking such events as the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, and also identified buildings and sites associated with slavery, such as the former market site. With the opening of the monument, the city was ranked by the New York Times as its Top 2018 Destination. Lee Sentell of the Alabama Department of Tourism acknowledged that the National Memorial offers a different and painful encounter: “Most museums are somewhat objective and benign…This one is not. This is aggressive, political. … It’s a part of American history that has never been addressed as much in your face as this story is being told”. Mayor Todd Strange suggested that the memorial offered “our nation’s best chance at reconciliation”.

The opening celebrations, in May 2018, attracted thousands of people to Montgomery, perhaps as many as 10,000. Artists who performed included Stevie Wonder, Patti LaBelle, and Usher; speakers included Congressman and civil rights activist John Lewis from Georgia.

The memorial and its attendant museum are expected to generate heightened tourism for Montgomery , even if it is dark tourism. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution noted that, with the addition of the memorial and the museum, Montgomery and Atlanta together provide a narrative of African-American history, as the latter has sites associated with national leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and local history as well. Tourism officials said that possibly 100,000 extra visitors per year may arrive.

The Legacy Museum

Opened on the same date as the outdoor memorial, The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration is a museum that displays and interprets the history of slavery and racism in America. The progress through the museum is chronological, beginning with slavery, and passing through the decades of lynching, extrajudicial violence against blacks, through the Civil Rights era, and dealing with present issues. This includes the enslavement of African-Americans, racial lynchings and disenfranchisement of black voters, segregation and Jim Crow, and racial bias. Artwork in the museum includes a sculpture on slavery by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, at the beginning; a sculpture “dedicated to the women who sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott” by Dana King, to help illustrate the Civil Rights period; and a piece about today’s police violence and the biased criminal justice system, by Hank Willis Thomas.

The museum features artwork by Hank Willis Thomas, Glenn Ligon, Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, Titus Kaphar, and Sanford Biggers. One of its displays is a collection of soil from lynching sites across the United States. This exhibit expresses the vast effects of slavery, lynchings, and black oppression across state lines. The exhibits in the 11,000-square-foot museum include oral history, archival materials, and interactive technology.

Publishers of the Montgomery Advertiser reviewed and formally apologized for its historic coverage of lynchings, which was often inflammatory against black victims, describing it as “our shame” and saying “we were wrong”.

via Wikipedia

———

By Holland Cotter

June 1, 2018

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Arthur St. Clair, a minister, was lynched in Hernando County, Florida, in 1877 for performing the wedding of a black man and white woman.

Fred Rochelle, 16, was burned alive in a public spectacle lynching before thousands in Polk County, Florida, in 1901.

David Walker, his wife, and their four children were lynched in Hickman, Kentucky, in 1908 after Mr. Walker was accused of using inappropriate language with a white woman.

Lacy Mitchell was lynched in Thomasville, Georgia, in 1930 for testifying against a white man accused of raping a black woman.

Jesse Thornton was lynched in Luverne, Alabama, in 1940 for addressing a white police officer without the title “mister.”

These appalling death notices — there are 90 in all, based on archival accounts dating from between 1877 and 1950 — fall like blows as you read them, one after another, lined up like epitaphs on a long wall at the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice in this city. And the shock spreads and deepens when you delve into the larger, and continuing, story of American racial violence as told in another newly opened cultural site here, the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration.

Historically, accounts of the lynching of African-Americans appeared in regional newspapers but seldom made their way into the North-based mainstream press. Photographs were rarely published anywhere. (These existed, but usually circulated privately, sometimes as postcards.) The most visible alert New York City had of such killings came from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which periodically flew a flag from its Fifth Avenue office window reading “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” Mostly, though, lynching met with public silence, which lasted a long time.

That silence has been decisively broken with the opening of the memorial and the museum. Both were created by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit legal advocacy group directed by Bryan Stevenson and based in Montgomery. Both address the subject of history in a way unusual until recently for American institutions: with a truth-telling, uplift-free prosecutorial directness. And both approach it by different means.

via: nytimes

—

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened to the public on April 26, 2018, is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.

Work on the memorial began in 2010 when EJI staff began investigating thousands of racial terror lynchings in the American South, many of which had never been documented. EJI was interested not only in lynching incidents, but in understanding the terror and trauma this sanctioned violence against the black community created. Six million black people fled the South as refugees and exiles as a result of these “racial terror lynchings.”

This research ultimately produced Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror in 2015 which documented thousands of racial terror lynchings in 12 states. Since the report’s release, EJI has supplemented its original research by documenting racial terror lynchings in states outside the Deep South. EJI staff have also embarked on a project to memorialize this history by visiting hundreds of lynching sites, collecting soil, and erecting public markers, in an effort to reshape the cultural landscape with monuments and memorials that more truthfully and accurately reflect our history.

The Memorial for Peace and Justice was conceived with the hope of creating a sober, meaningful site where people can gather and reflect on America’s history of racial inequality. EJI partnered with artists like Kwame Akoto-Bamfo whose sculpture on slavery confronts visitors when they first enter the memorial. EJI then leads visitors on a journey from slavery, through lynching and racial terror, with text, narrative, and monuments to the lynching victims in America. In the center of the site, visitors will encounter a memorial square, built in collaboration with MASS Design Group. The memorial experience continues through the civil rights era made visible with a sculpture by Dana King dedicated to the women who sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Finally, the memorial journey ends with contemporary issues of police violence and racially biased criminal justice expressed in a final work created by Hank Willis Thomas. The memorial displays writing from Toni Morrison and Elizabeth Alexander, words from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and a reflection space in honor of Ida B. Wells.

Set on a six-acre site, the memorial uses sculpture, art, and design to contextualize racial terror. The site includes a memorial square with 800 six-foot monuments to symbolize thousands of racial terror lynching victims in the United States and the counties and states where this terrorism took place.

The memorial structure on the center of the site is constructed of over 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns. The memorial is more than a static monument. It is EJI’s hope that the National Memorial inspires communities across the nation to enter an era of truth-telling about racial injustice and their own local histories.

The Community Remembrance Project is one tool EJI offers to support communities looking to engage in this work. EJI’s community remembrance work is part of a larger movement to create an era of restorative truth-telling and justice that changes the consciousness of our nation. We work with communities to erect historical markers, organize soil collection ceremonies, and hold essay contests for local high school students to support the development of local, community-led efforts to engage with and discuss past and present issues of racial justice. After active Community Remembrance work, EJI will also collaborate to place a monument—identical to the monument found at the National Memorial—in the community. EJI believes that markers and monuments can help transform our national landscape into a more honest reflection of the history of America and reflect a community’s ongoing commitment to truth-telling and racial justice.

When a county’s memorial monument is installed, as a culminating feature of that community work and dialogue, we hope that it can represent the accomplishment of the work done so far, and stand as a symbolic reminder of the community’s continuing efforts to truthfully grapple with painful racial history, challenge injustice where it exists in their own lives, and vow never to repeat the terror and violence of the past.

The process of local communities claiming their memorial monuments is thus about much more than transporting and installing the physical monuments themselves. Rather, it first requires an effort to encourage communities across the nation to engage in genuine and sustained work that advances a new era of truth and justice by confronting racial history in a way most communities have never done. EJI’s Community Remembrance Project is one form that work can take, and we are proud to offer our tools and resources to communities interested in using that partnership to advance those goals. Community coalitions who complete community soil collection and narrative historical marker projects, or pursue other, independent community efforts to foster dialogue and remembrance, help raise local consciousness of racial history and help foster dialogue about the connections to contemporary issues and further develop a communal identity that prioritizes historical truth-telling and repair.

Lynching in America

In the report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, EJI documented more than 4400 lynchings of black people in the United States between 1877 and 1950. EJI identified 800 more lynchings than had previously been recognized.

Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order. These lynchings were terrorism.

The lynching era left thousands dead; it significantly marginalized black people in the country’s political, economic, and social systems; and it fueled a massive migration of black refugees out of the South. In addition, lynching – and other forms of racial terrorism – inflicted deep traumatic and psychological wounds on survivors, witnesses, family members, and the entire African American community.

Why Build a Memorial to Victims of Racial Terror?

EJI believes that publicly confronting the truth about our history is the first step towards recovery and reconciliation.

A history of racial injustice must be acknowledged, and mass atrocities and abuse must be recognized and remembered, before a society can recover from mass violence. Public commemoration plays a significant role in prompting community-wide reconciliation.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy.

The museum and memorial are part of EJI’s work to advance truth and reconciliation around race in America and to more honestly confront the legacy of slavery, lynching, and segregation. “Our nation’s history of racial injustice casts a shadow across the American landscape,” EJI Director Bryan Stevenson explains. “This shadow cannot be lifted until we shine the light of truth on the destructive violence that shaped our nation, traumatized people of color, and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice.”

Modeled on important projects used to overcome difficult histories of genocide, apartheid, and horrific human rights abuses in other countries, EJI’s sites are designed to promote a more hopeful commitment to racial equality and just treatment of all people.

The April 26 opening was accompanied by several days of educational panels and presentations from leading national figures, performances and concerts from acclaimed recording artists, and a large opening ceremony. Thousands of visitors traveled to Montgomery to celebrate the launch of these important new American institutions.

The Peace and Justice Memorial Center

Built to enhance the public and community education goals of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the center is home to a new monument that honors victims of racial terror lynchings and racial violence between 1950 and 1959. The center is located on Caroline Street, directly across from the entrance to the National Memorial.

EJI staff offer presentations for museum and memorial visitors at the center at 2:30 PM daily (except Tuesdays and Sundays).

And the center will be hosting community events with nationally-acclaimed artists, writers, and scholars, films, and other programming to address a range of topics and issues related to the work of EJI, the Legacy Museum, and the National Memorial.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice