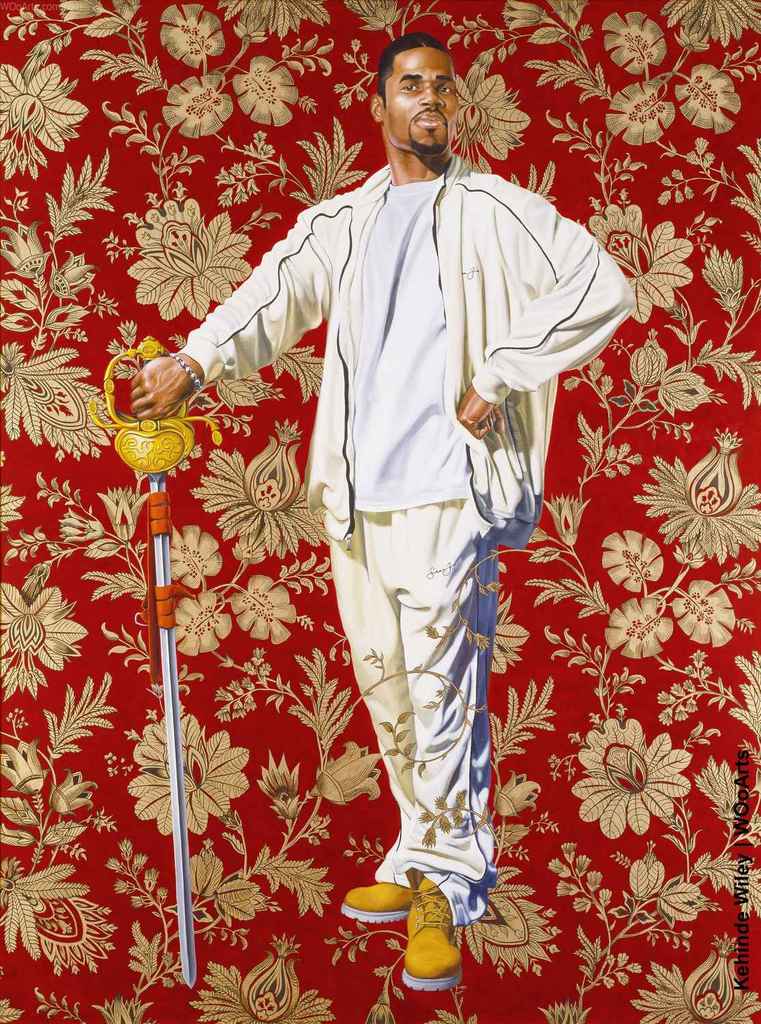

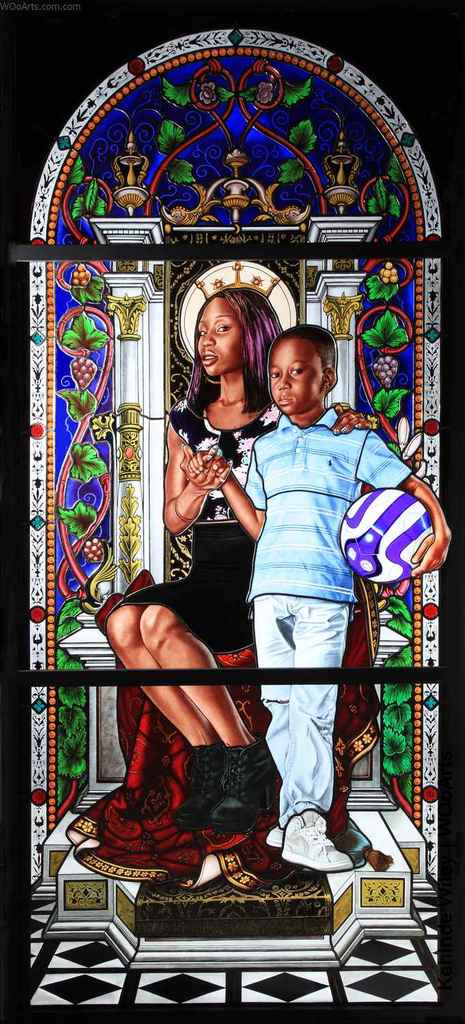

By applying the visual vocabulary and conventions of glorification, history, wealth and prestige to the subject matter drawn from the urban fabric, the subjects and stylistic references for his paintings are juxtaposed inversions of each other, forcing ambiguity and provocative perplexity to pervade his imagery.

Wiley’s larger than life figures disturb and interrupt tropes of portrait painting, often blurring the boundaries between traditional and contemporary modes of representation and the critical portrayal of masculinity and physicality as it pertains to the view of black and brown young men.

The World Stage

Initially, Wiley’s portraits were based on photographs taken of young men found on the streets of Harlem. As his practice grew, his eye led him toward an international view, including models found in urban landscapes throughout the world – such as Mumbai, Senegal, Dakar and Rio de Janeiro, among others – accumulating to a vast body of work called, “The World Stage.”

The models, dressed in their everyday clothing most of which are based on the notion of far-reaching Western ideals of style, are asked to assume poses found in paintings or sculptures representative of the history of their surroundings. This juxtaposition of the “old” inherited by the “new” – who often have no visual inheritance of which to speak – immediately provides a discourse that is at once visceral and cerebral in scope.

Without shying away from the complicated socio-political histories relevant to the world, Wiley’s figurative paintings and sculptures “quote historical sources and position young black men within the field of power.” His heroic paintings evoke a modern style instilling a unique and contemporary manner, awakening complex issues that many would prefer remain mute.

Kehinde Wiley Beginning

Kehinde Wiley started his anachronistic compositions by wandering casually through urban neighborhoods until someone’s distinct appearance and style catches his eye. He invites the person to his studio, where they page through art history books to select a classic portrait.

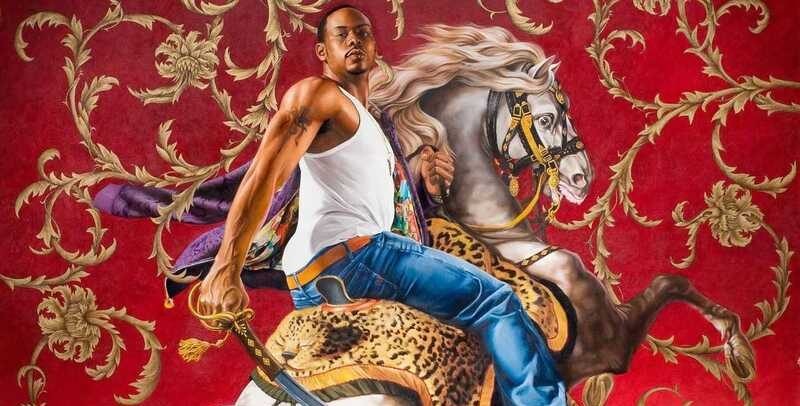

The “model” recreates the pose, which Wiley photographs for reference. In such paintings as Officer of the Hussars, Wiley inserts young African Americans into a tradition that has previously excluded them. Sitting high on a leopard skin saddle and wielding a sabre, Wiley’s model mirrors the subject of Théodore Géricault’s The Officer of the Hussars (1812; Musée du Louvre).

His garments—an athletic t-shirt, low-riding jeans, and Timberland shoes—differ from those of the European cavalry officer but serve to project a parallel image of confident masculine power.

Bringing visual codes into convergence, Wiley answers what he believes is the most important question in contemporary America: “Why do we continue to undervalue the lives of young black men?”

From Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 89 (2015)