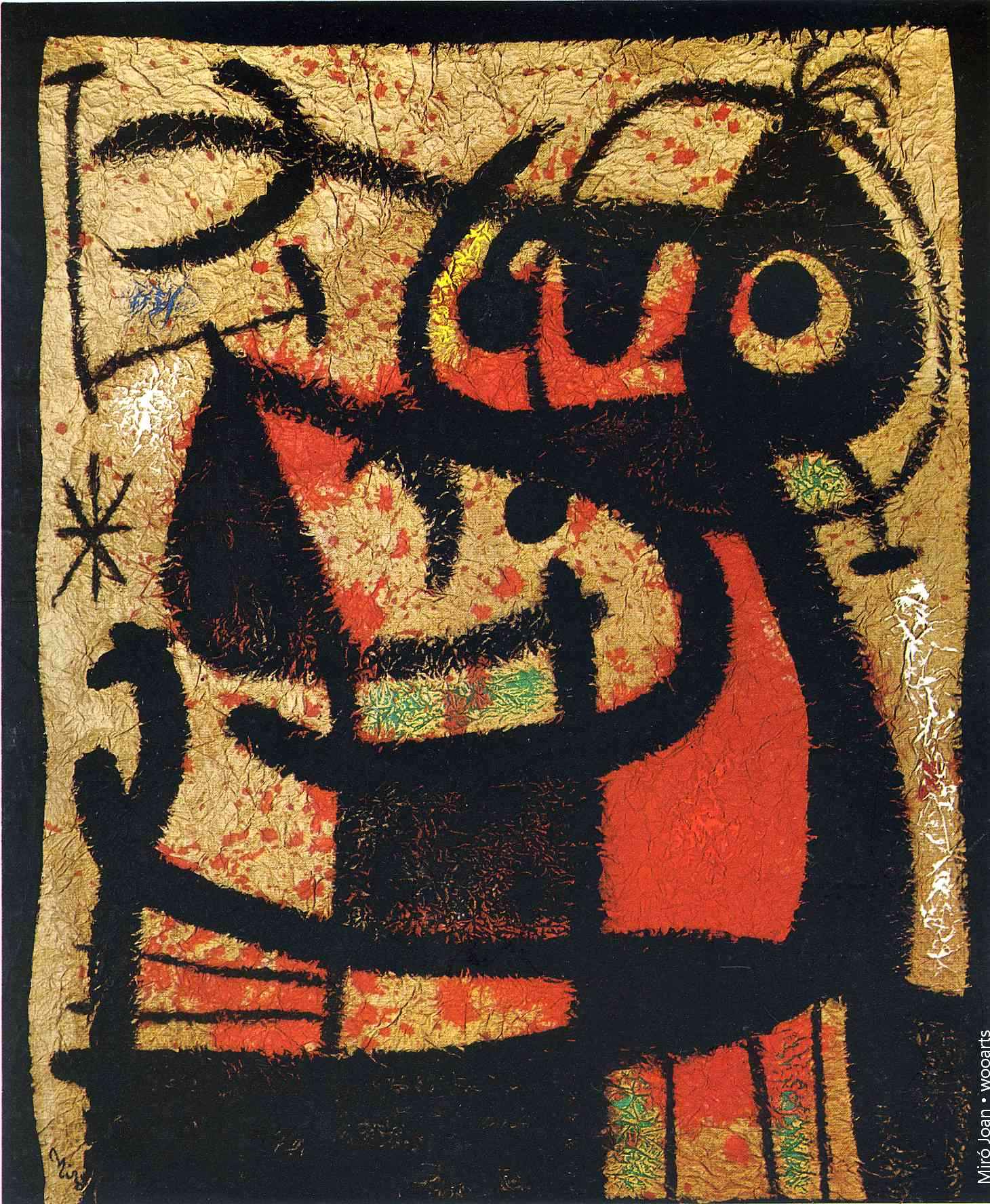

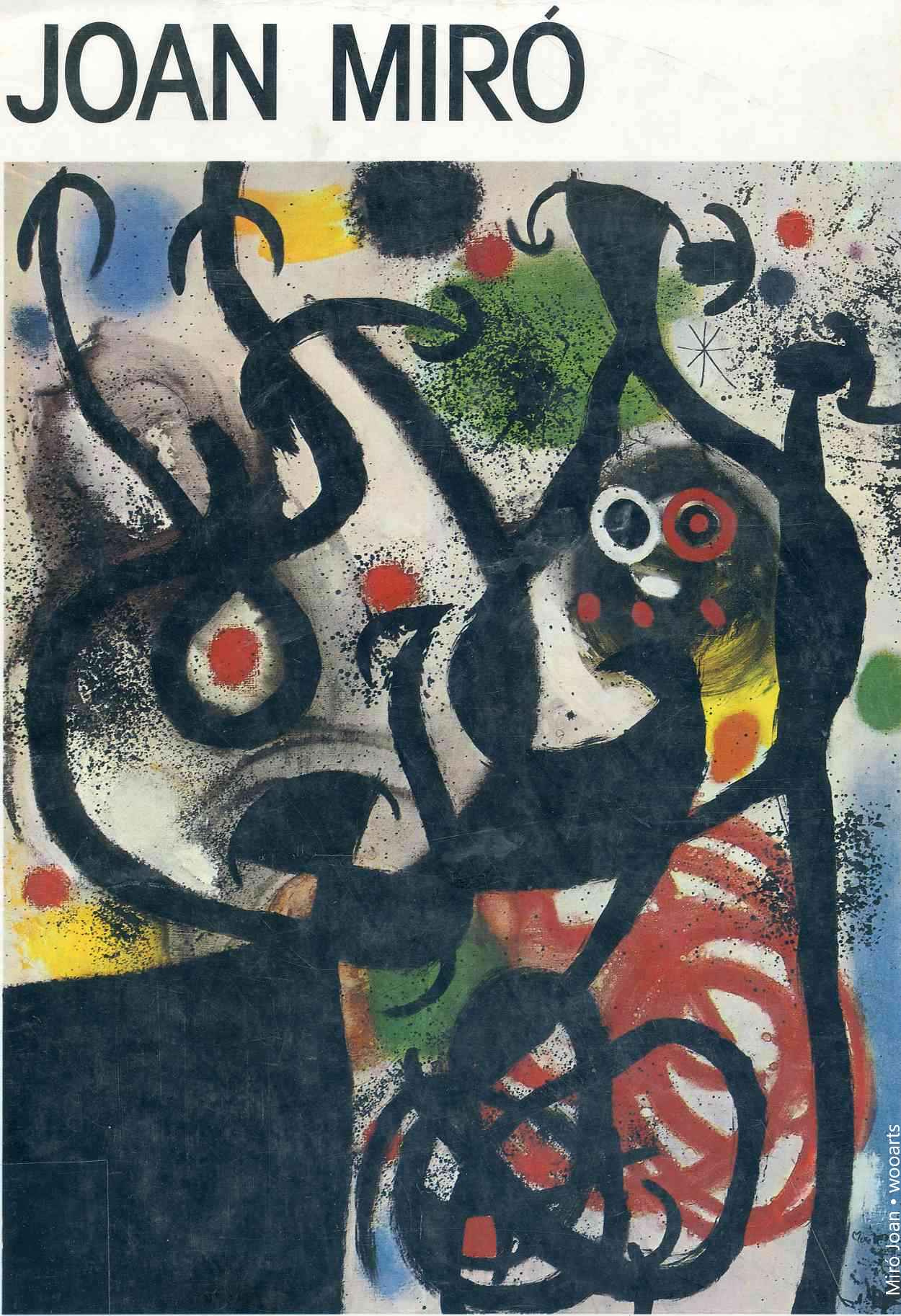

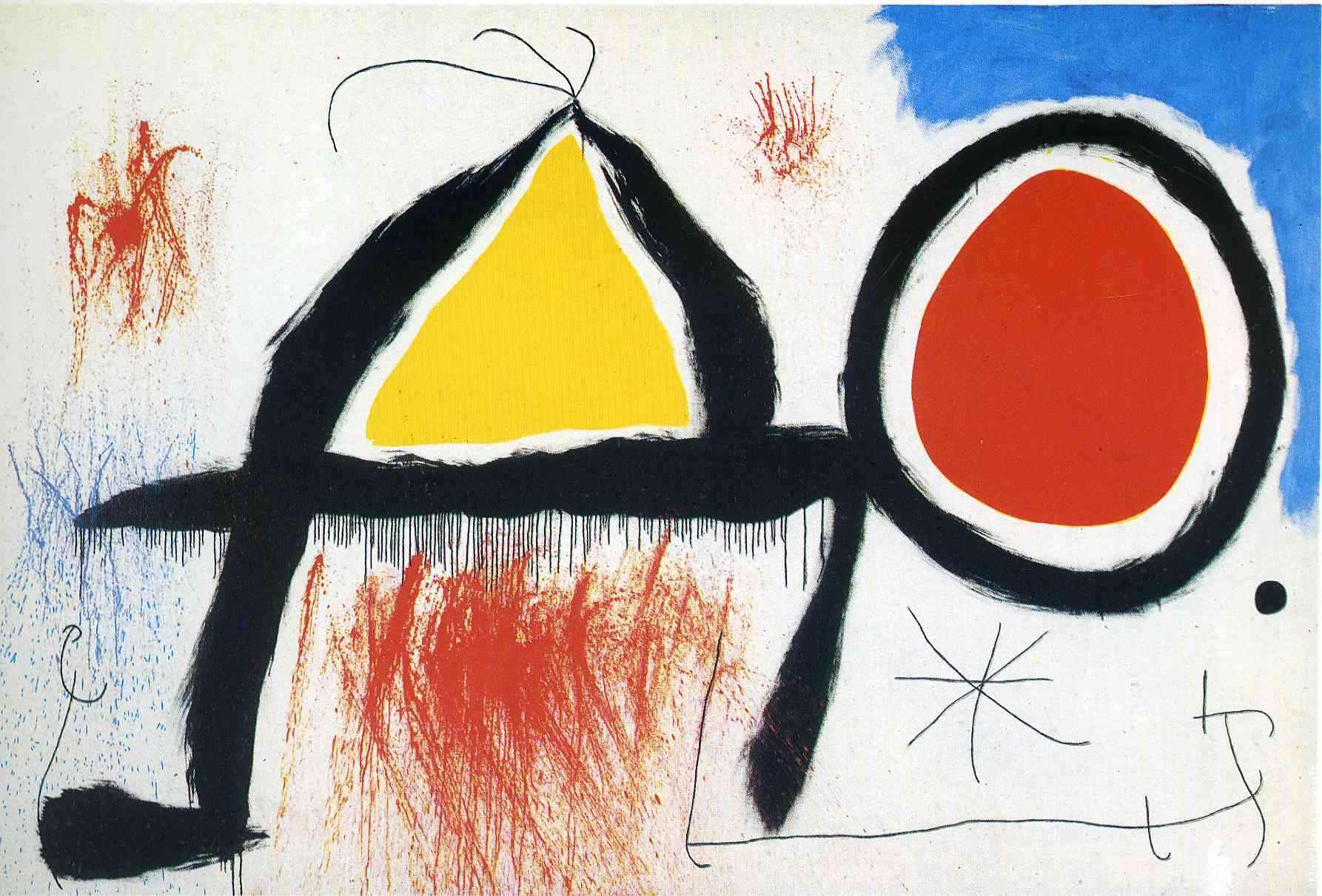

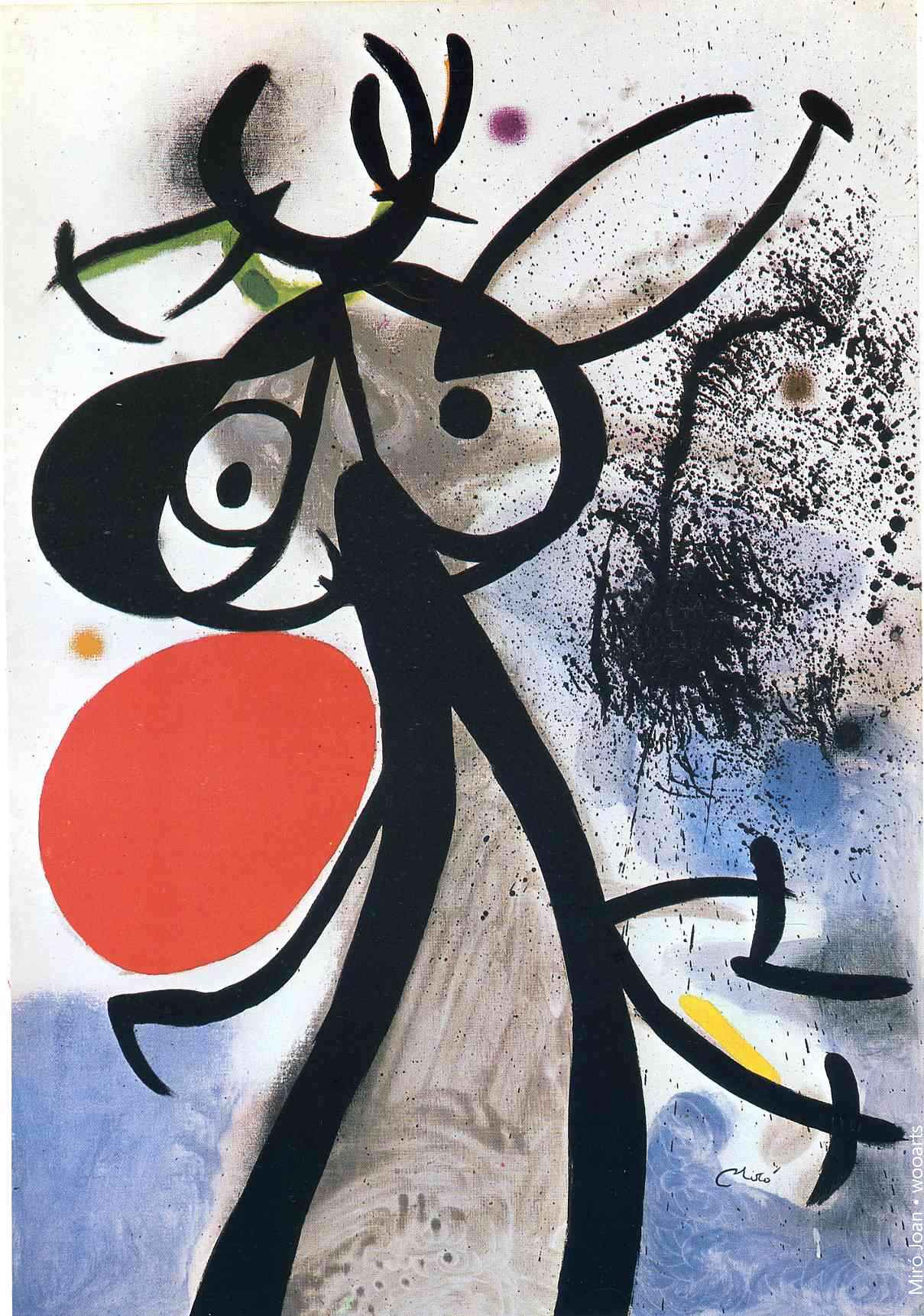

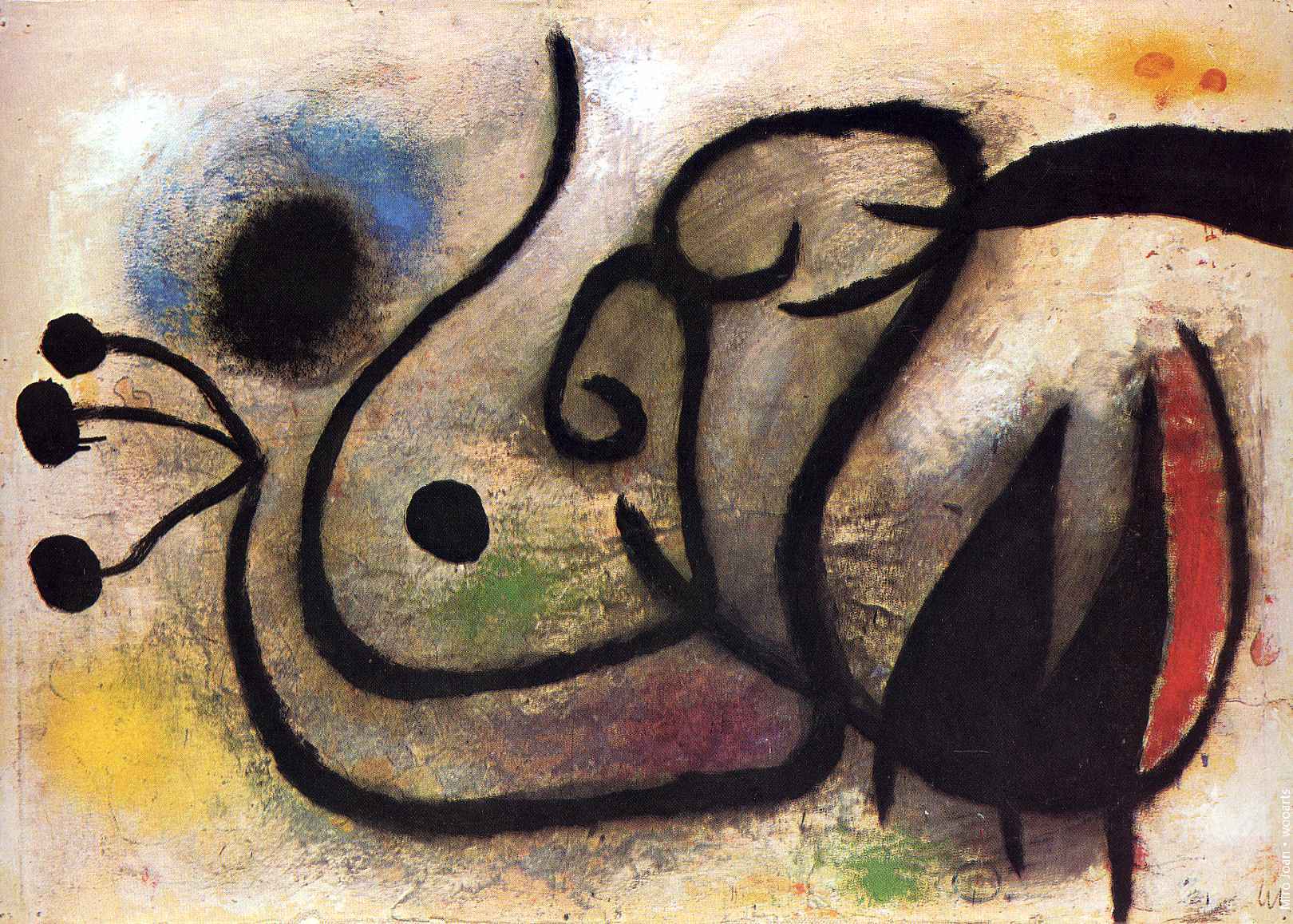

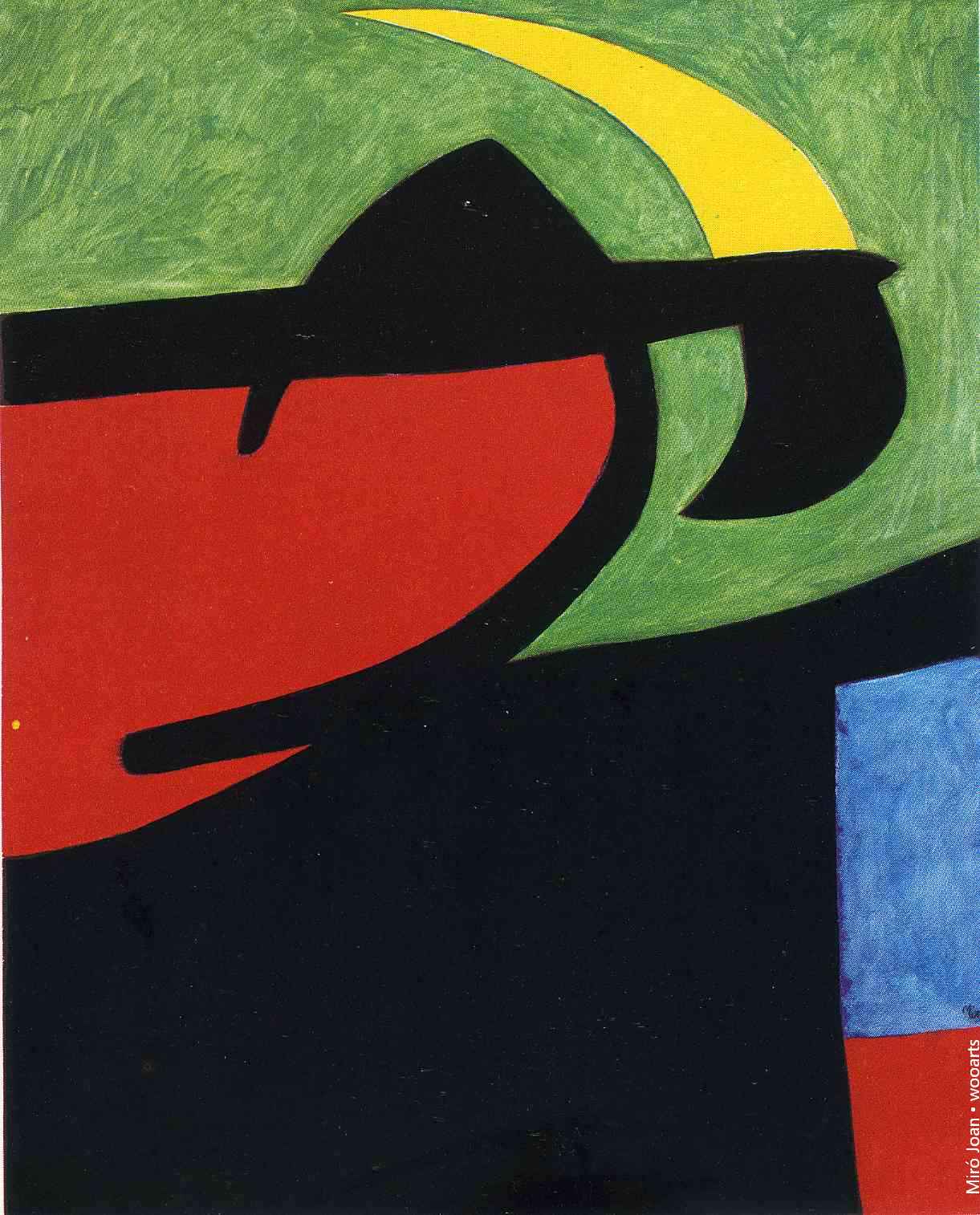

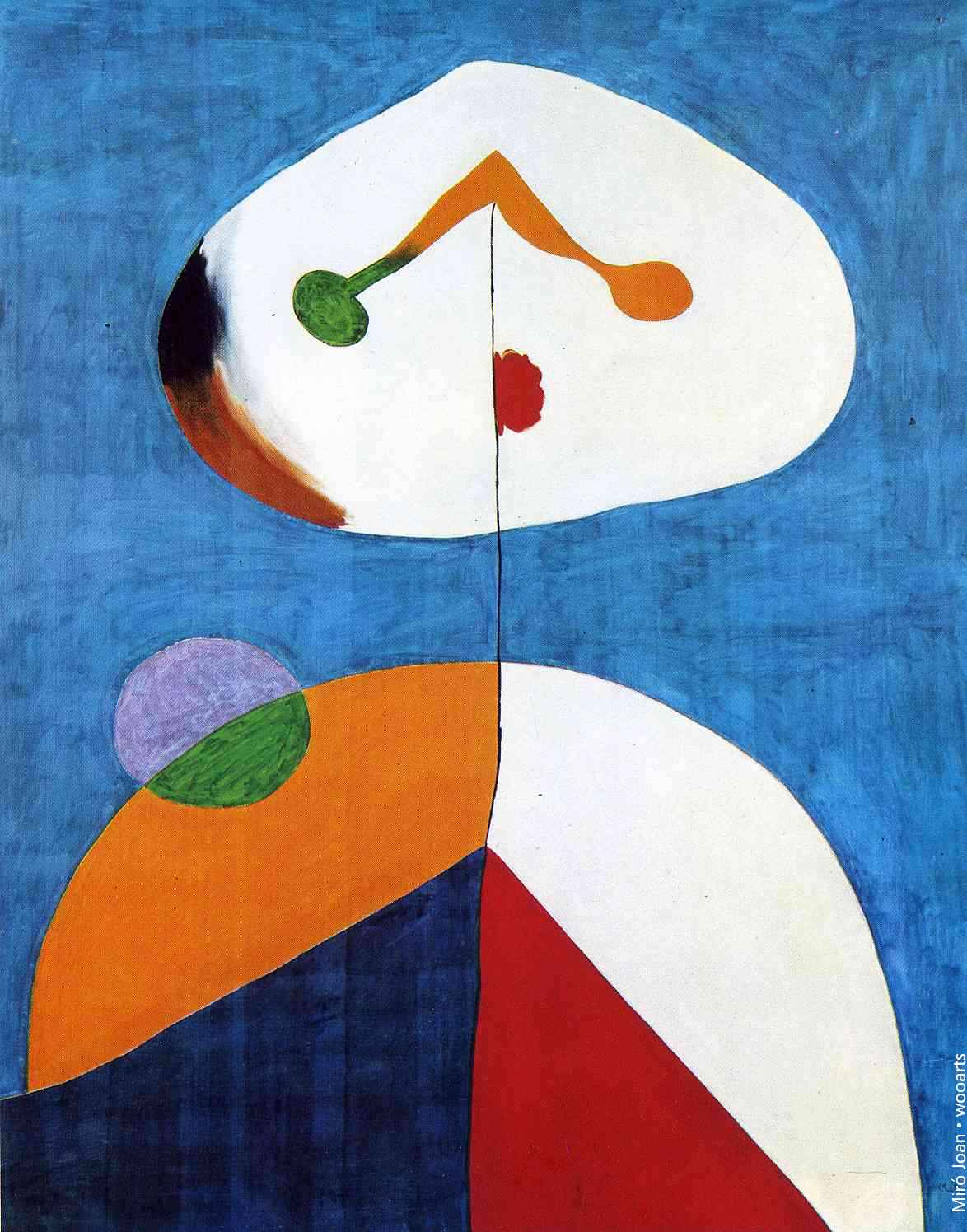

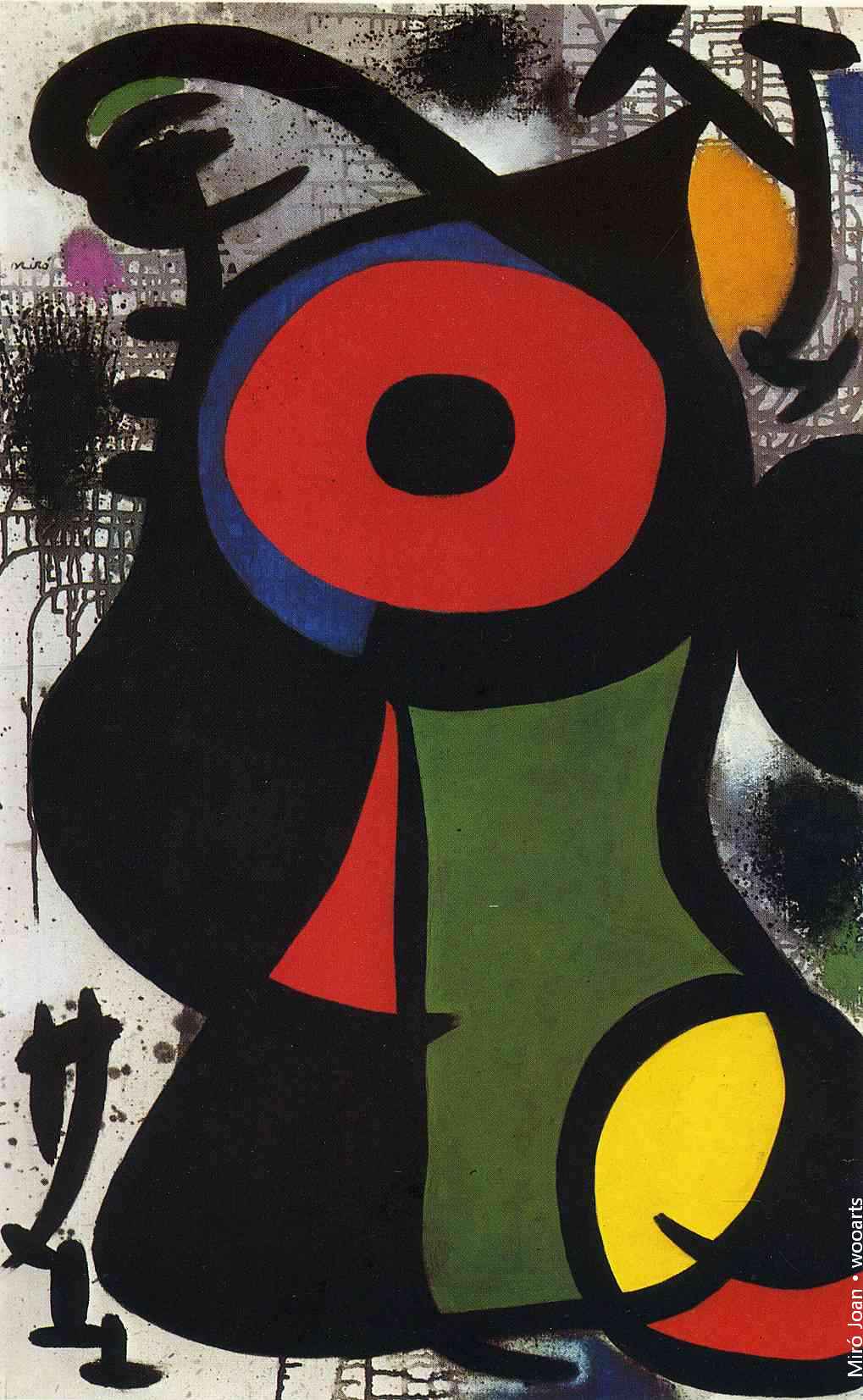

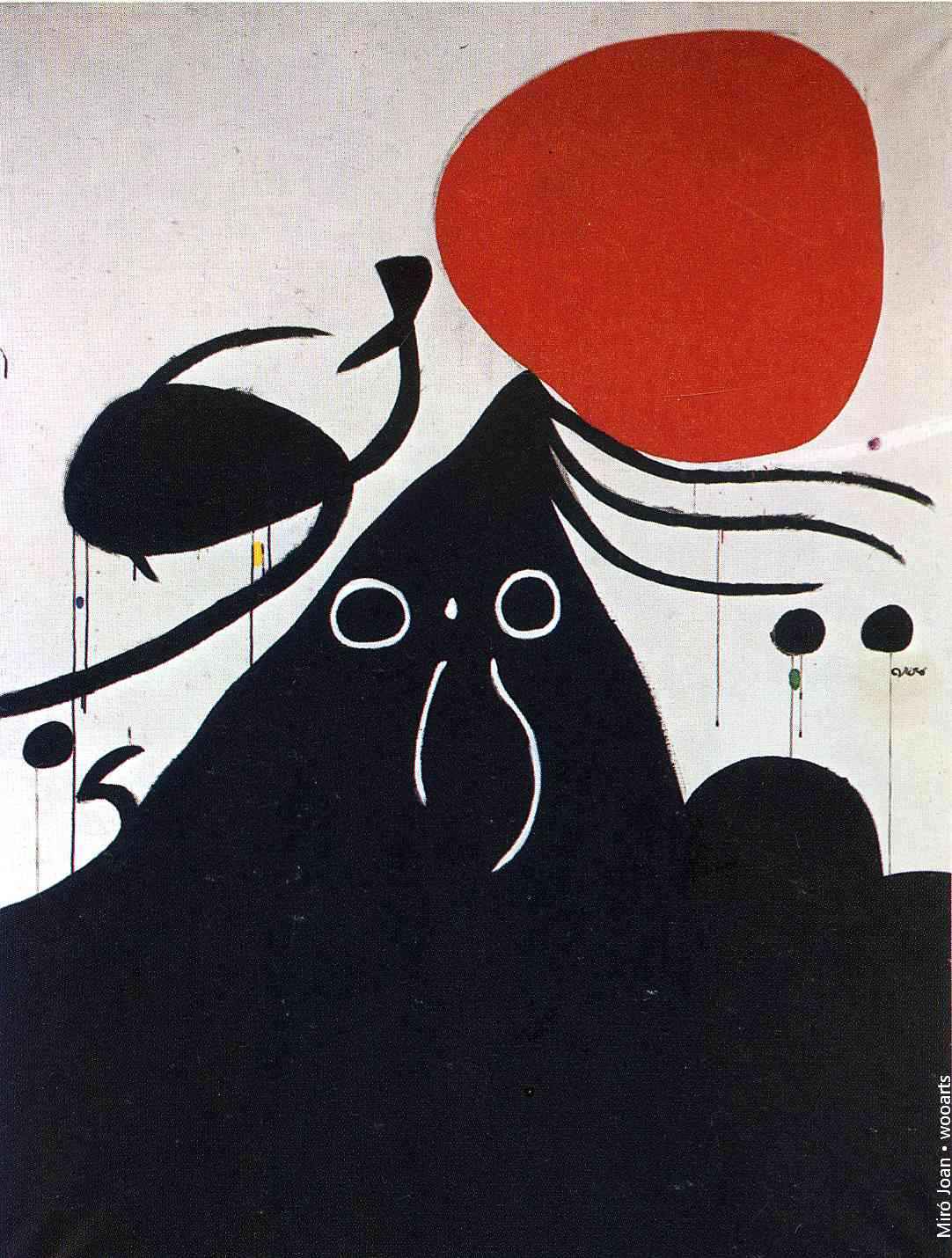

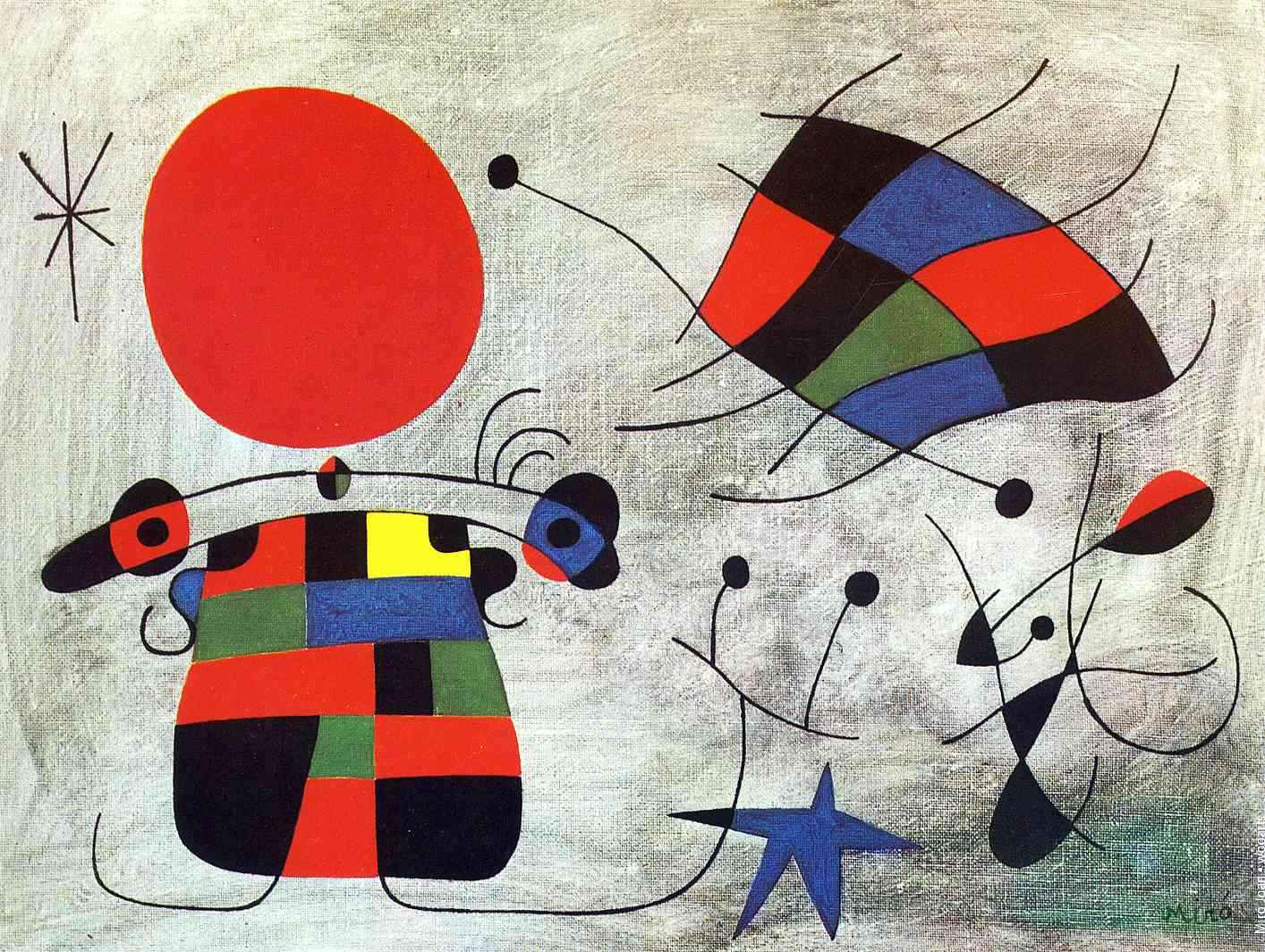

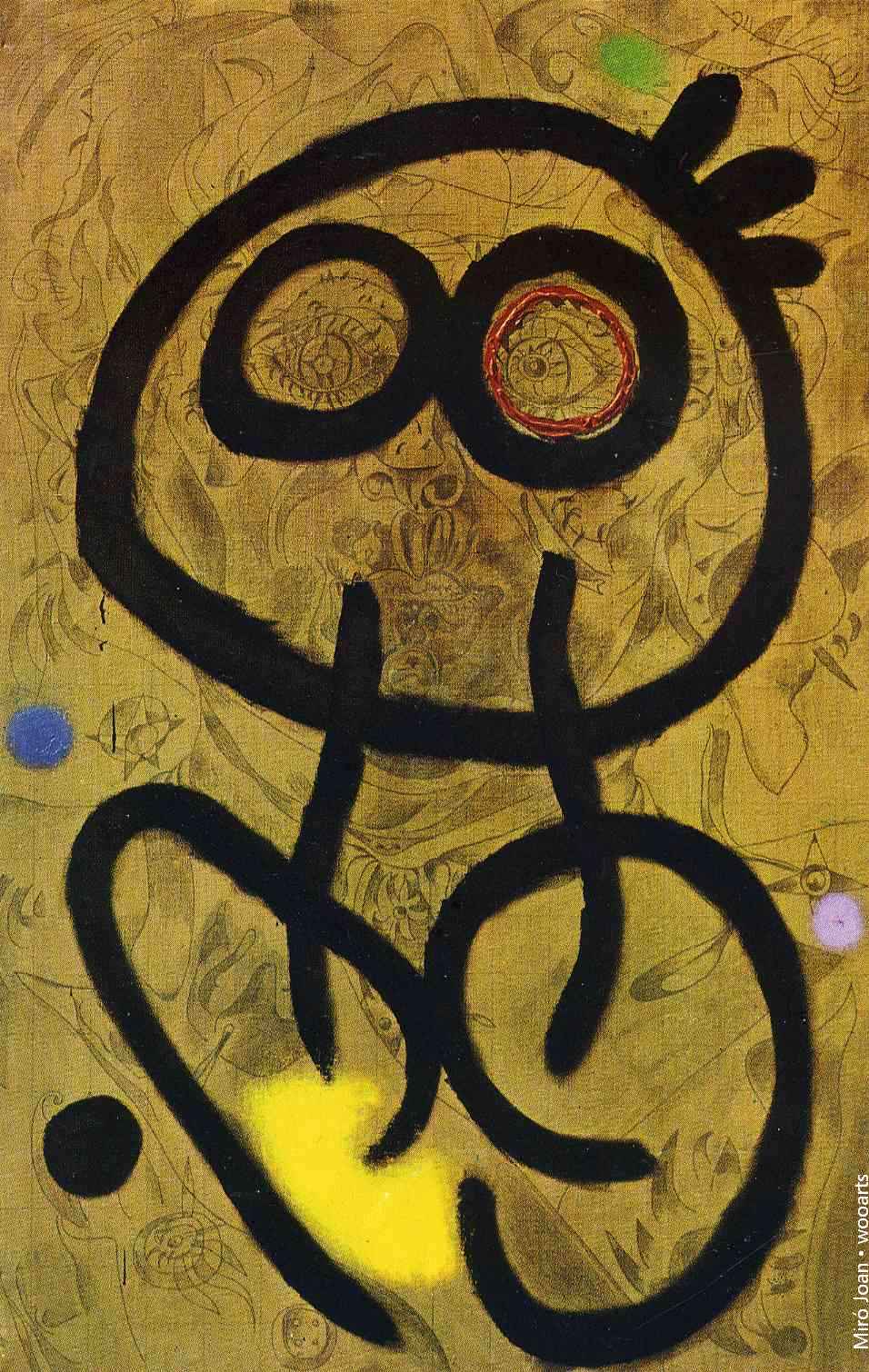

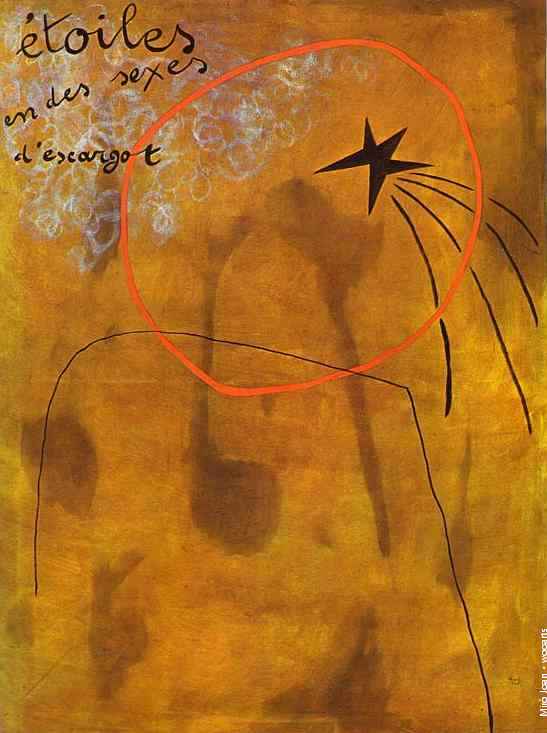

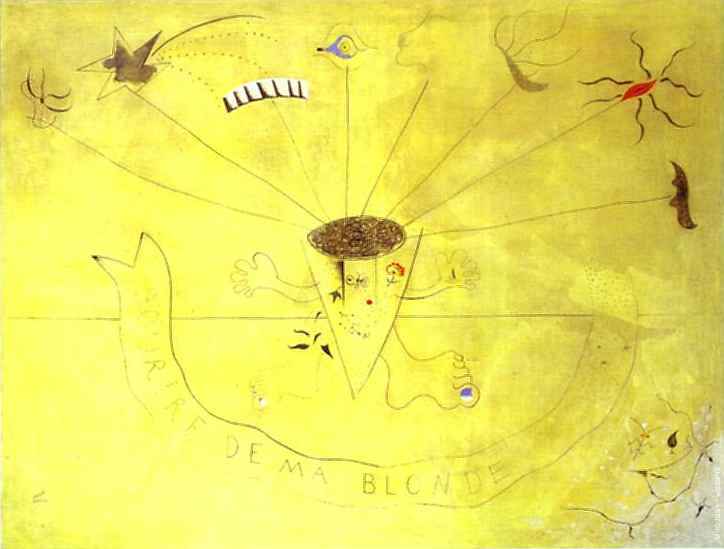

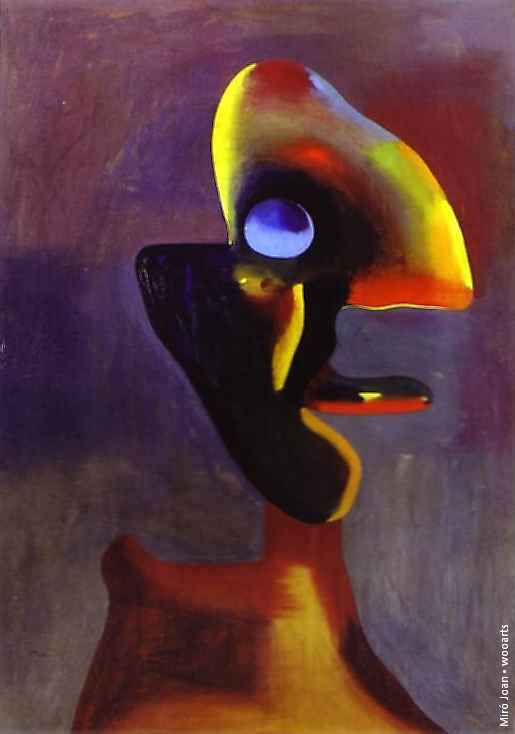

Earning international acclaim, his work has been interpreted as Surrealism but with a personal style, sometimes also veering into Fauvism and Expressionism. He was notable for his interest in the unconscious or the subconscious mind, reflected in his re-creation of the childlike. His difficult to classify works also had a manifestation of Catalan pride. In numerous interviews dating from the 1930s onwards, Miró expressed contempt for conventional painting methods as a way of supporting bourgeois society, and declared an “assassination of painting” in favour of upsetting the visual elements of established painting.

Biography

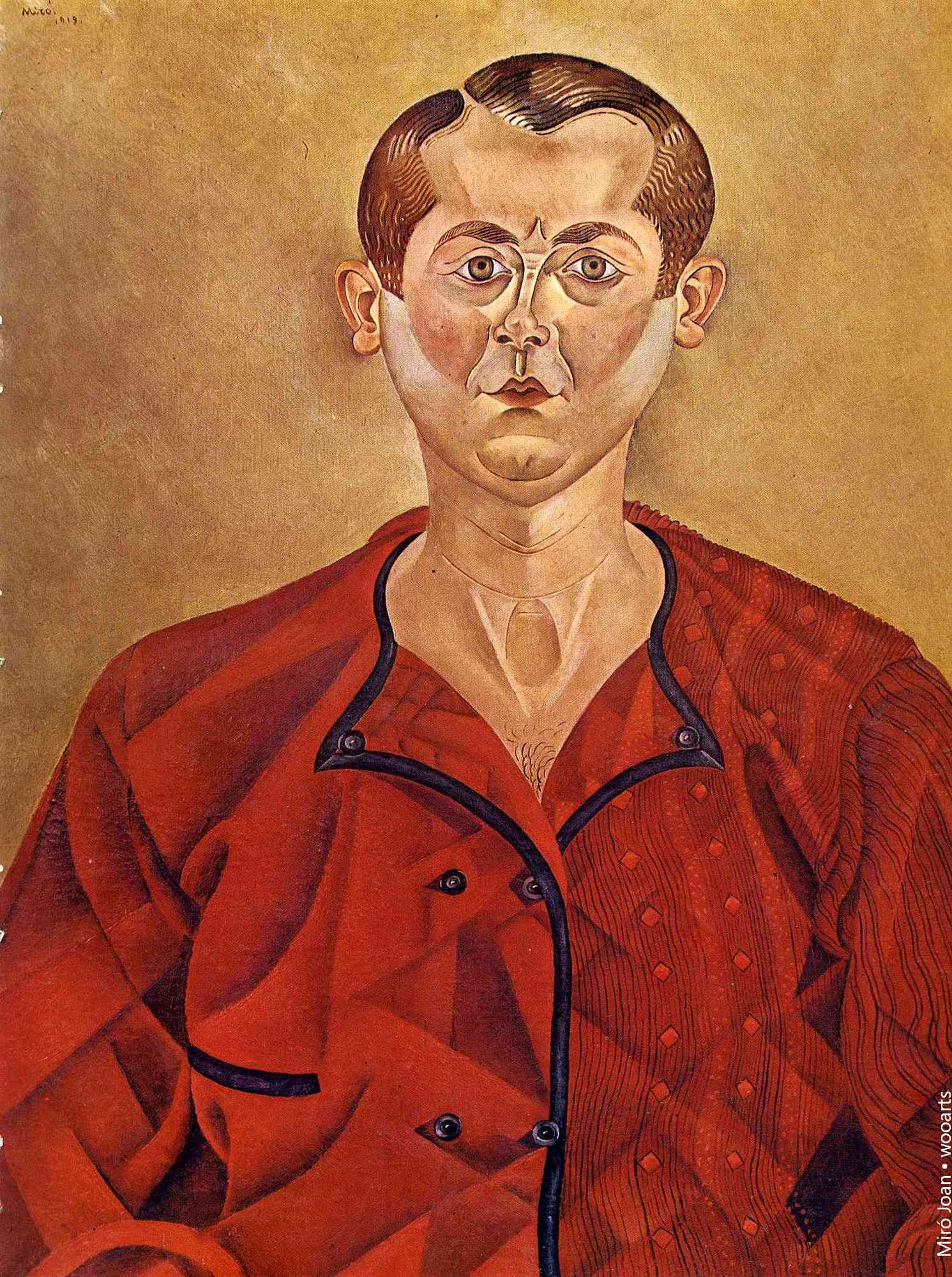

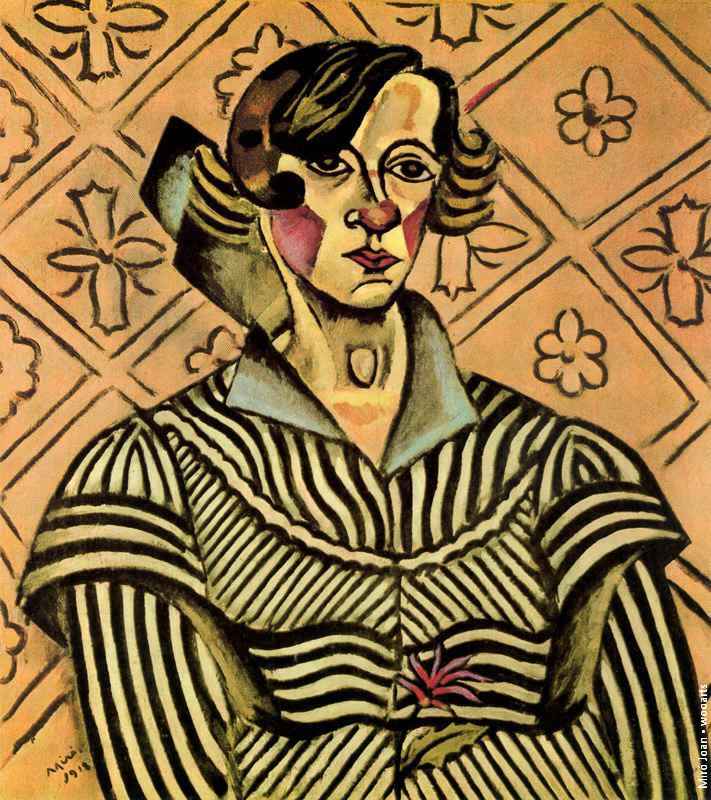

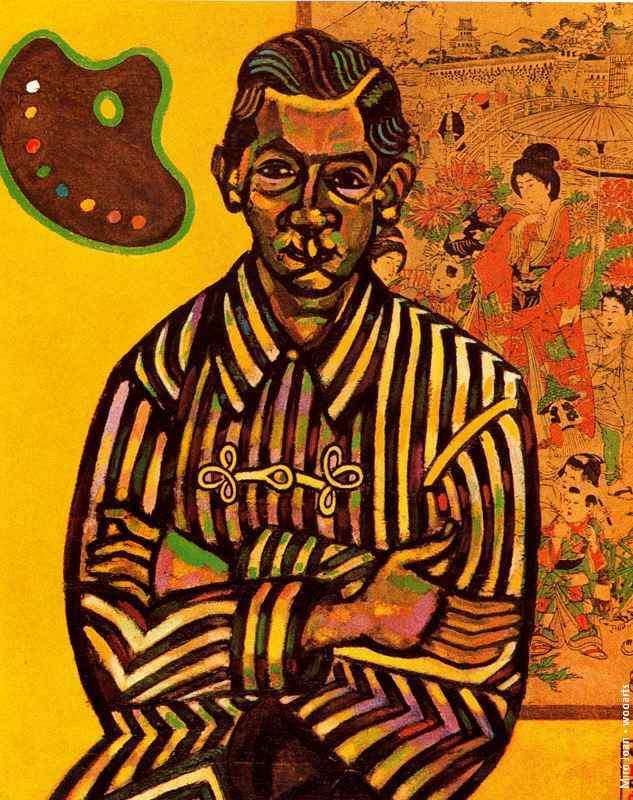

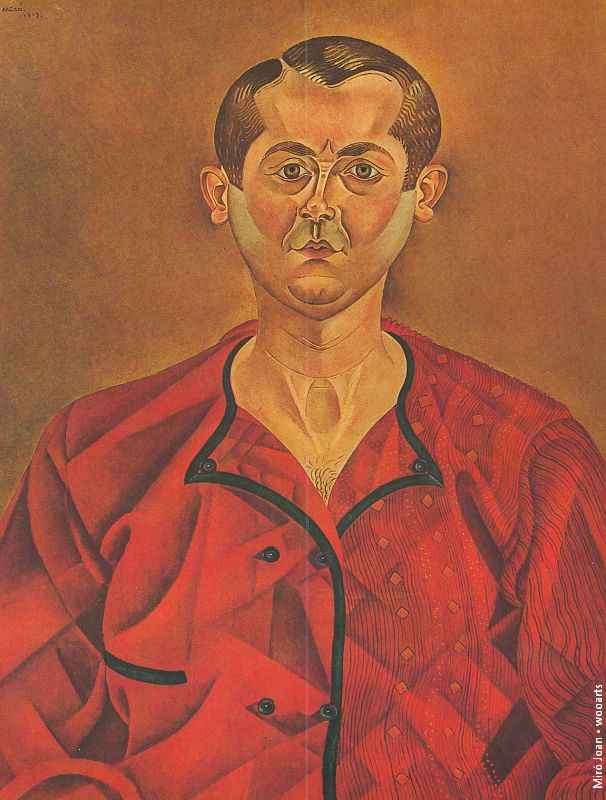

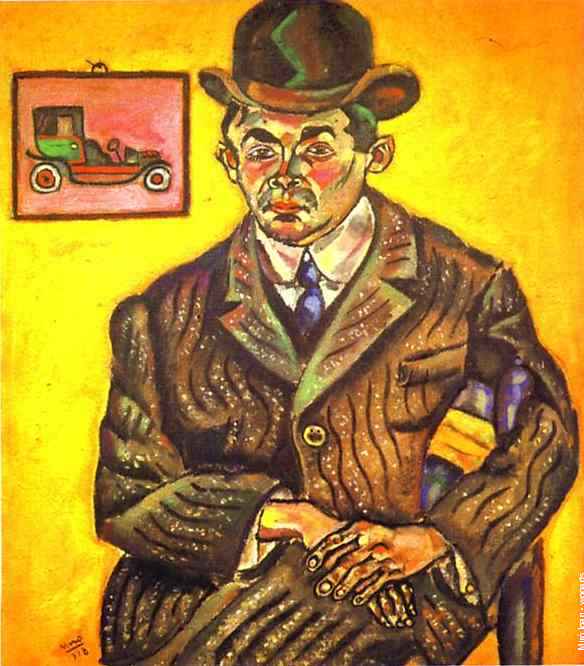

Born into a family of a goldsmith and a watchmaker, Miró grew up in the Barri Gòtic neighborhood of Barcelona. The Miró surname indicates possible Jewish roots (in terms of marrano or converso Iberian Jews who converted to Christianity). His father was Miquel Miró Adzerias and his mother was Dolors Ferrà. He began drawing classes at the age of seven at a private school at Carrer del Regomir 13, a medieval mansion. To the dismay of his father, he enrolled at the fine art academy at La Llotja in 1907. He studied at the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc and he had his first solo show in 1918 at the Galeries Dalmau, where his work was ridiculed and defaced. Inspired by Fauve and Cubist exhibitions in Barcelona and abroad, Miró was drawn towards the arts community that was gathering in Montparnasse and in 1920 moved to Paris, but continued to spend his summers in Catalonia.

Career

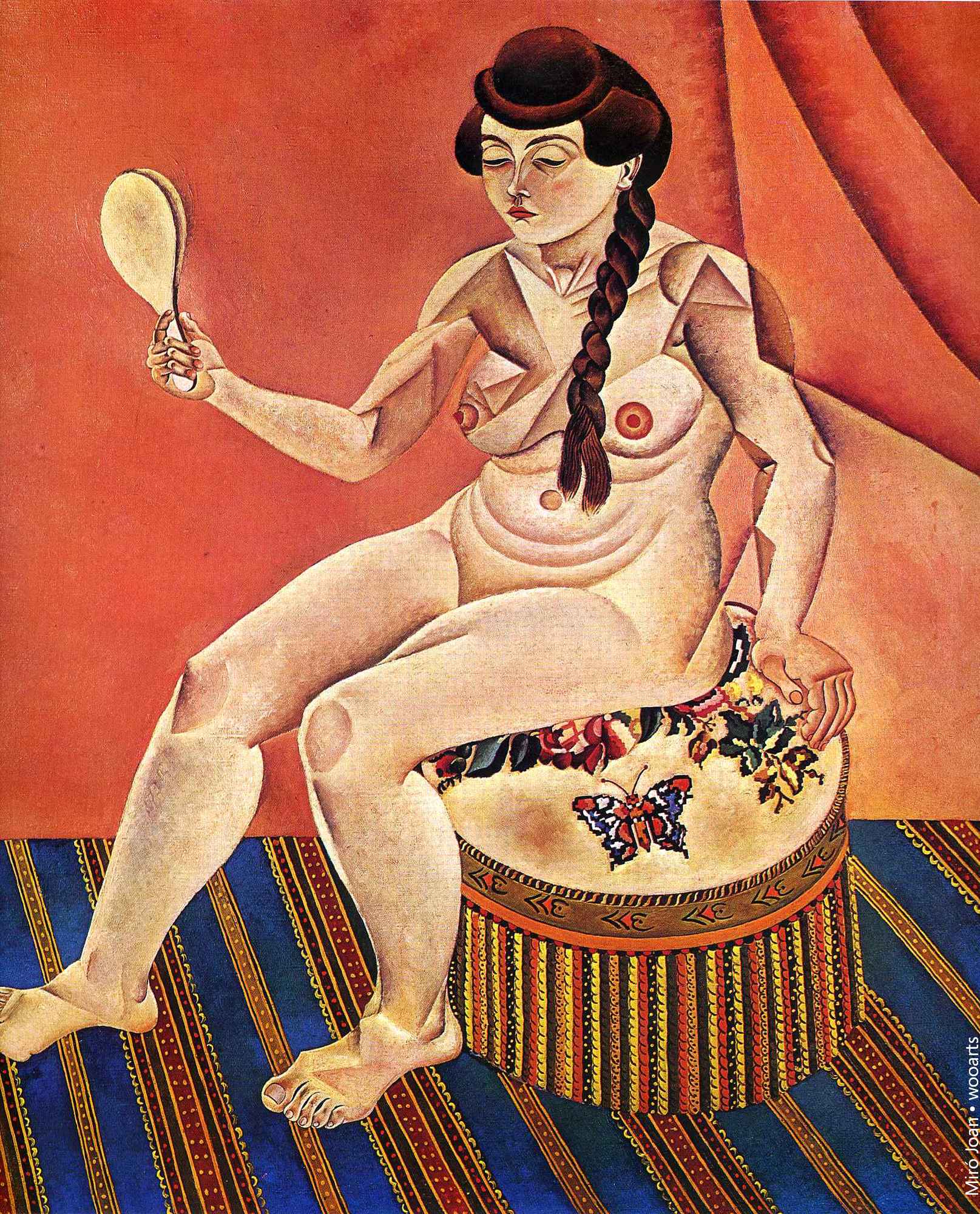

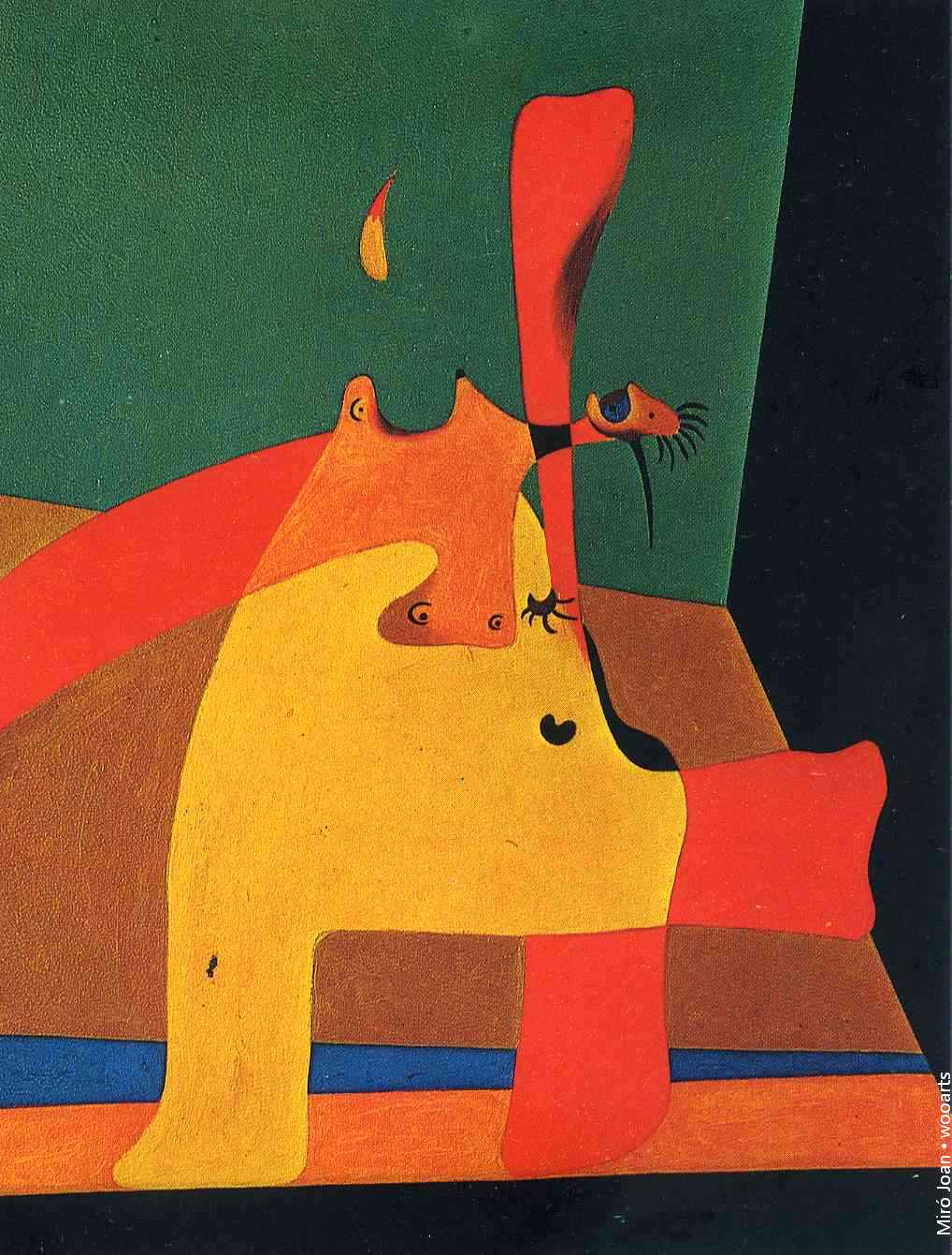

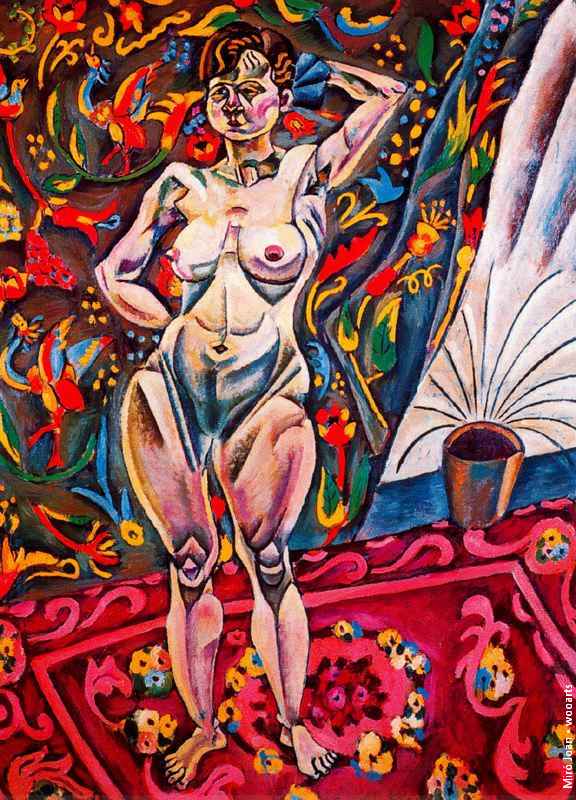

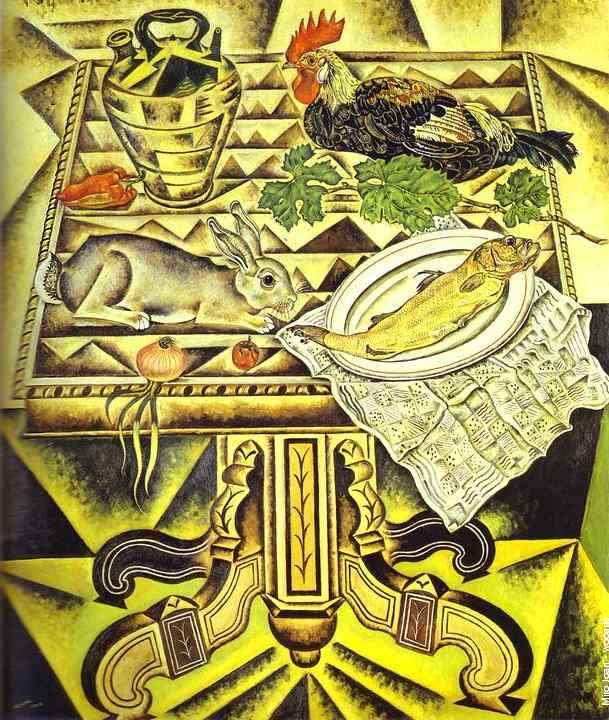

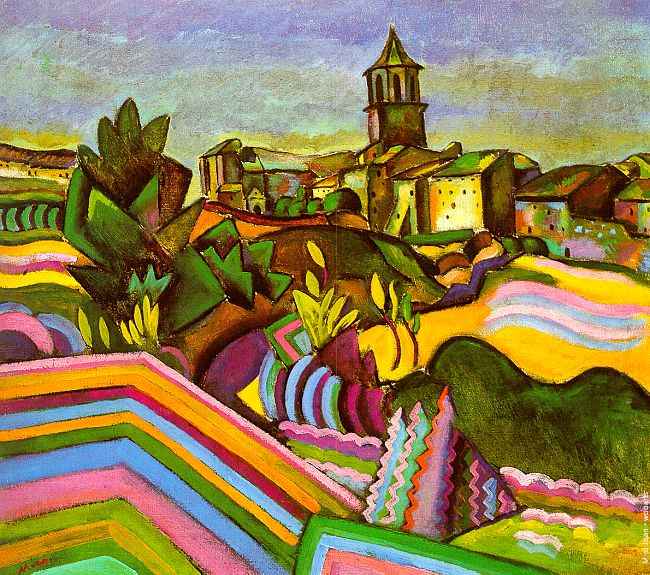

Miró initially went to business school as well as art school. He began his working career as a clerk when he was a teenager, although he abandoned the business world completely for art after suffering a nervous breakdown. His early art, like that of the similarly influenced Fauves and Cubists, was inspired by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne. The resemblance of Miró’s work to that of the intermediate generation of the avant-garde has led scholars to dub this period his Catalan Fauvist period.

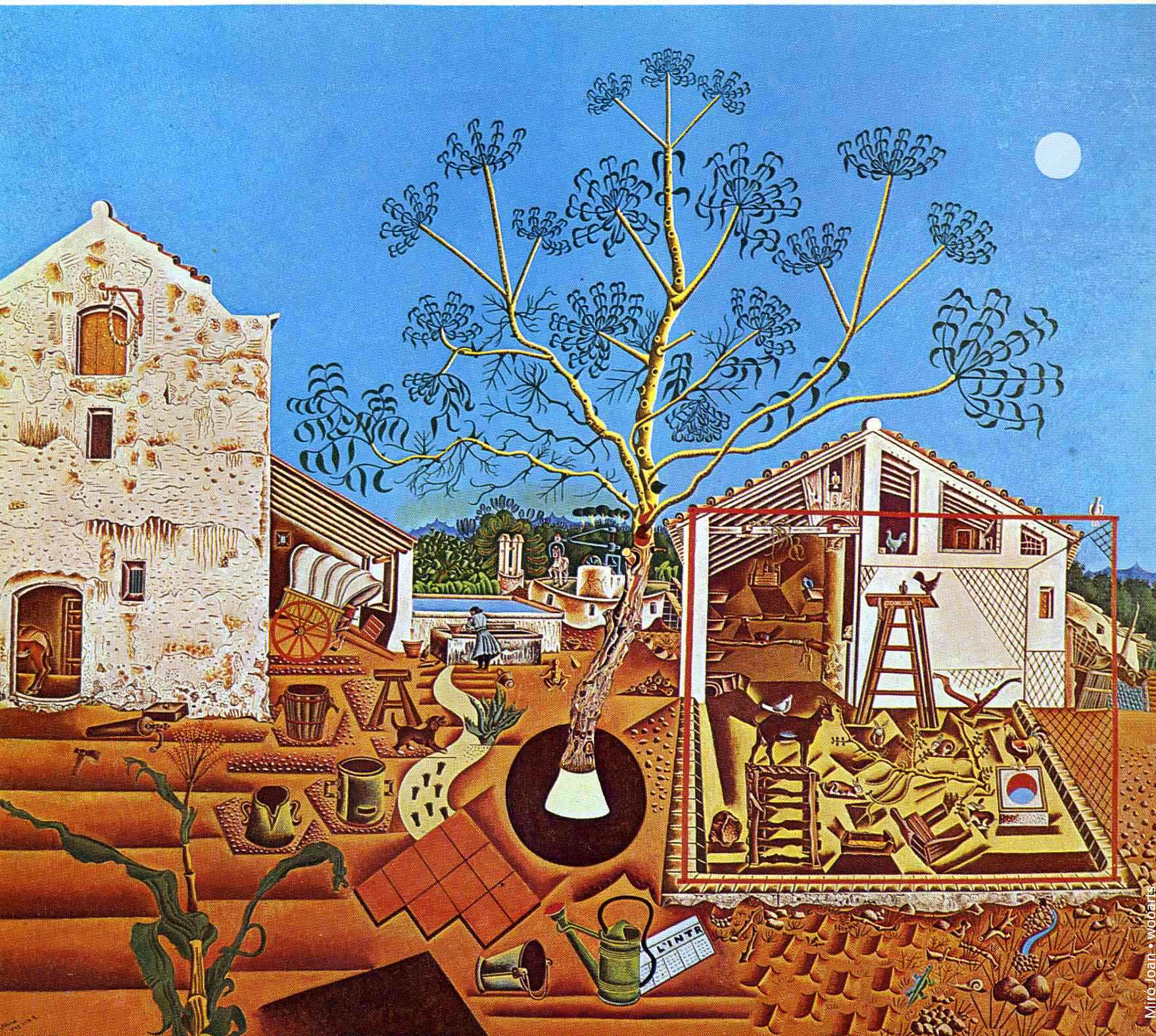

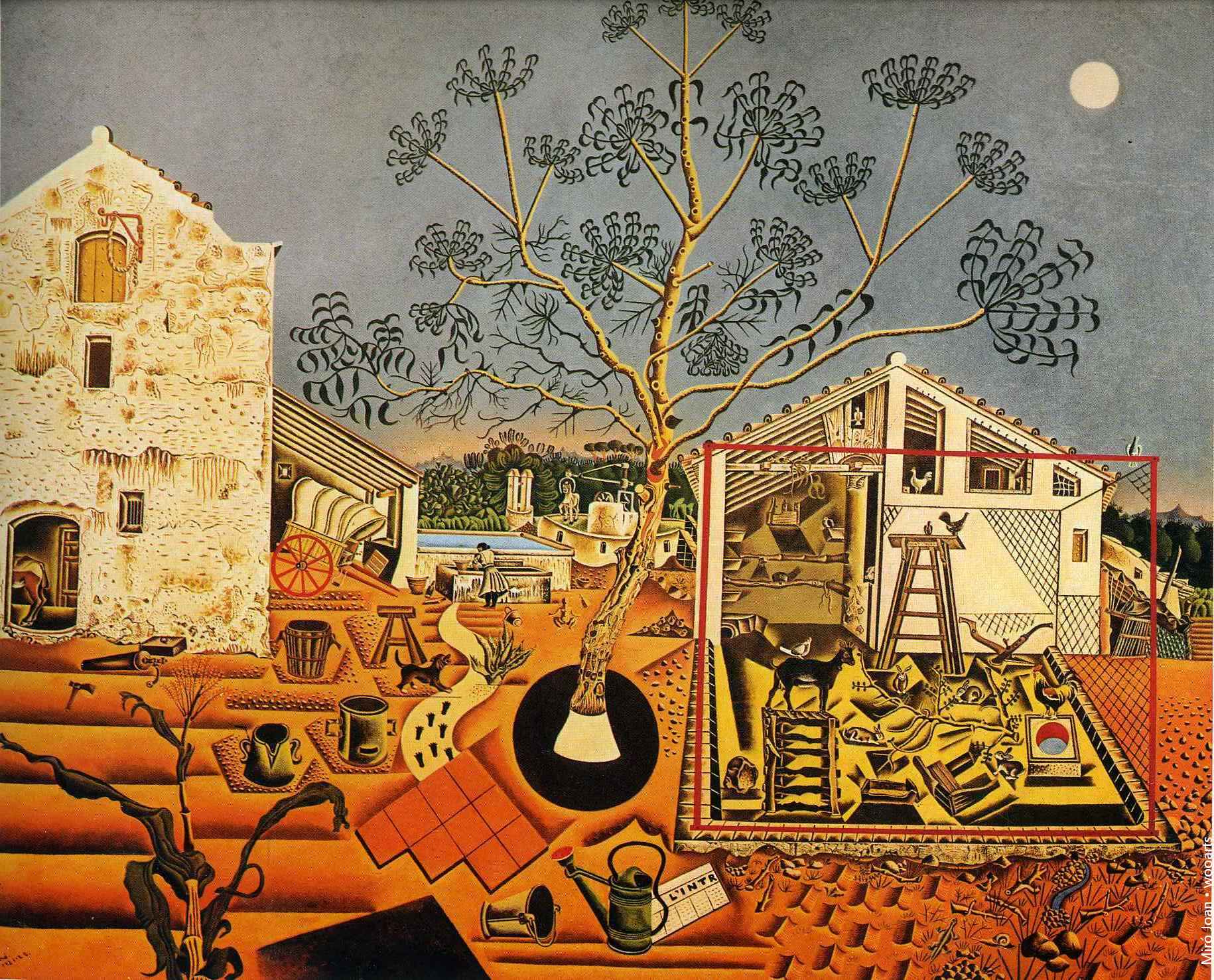

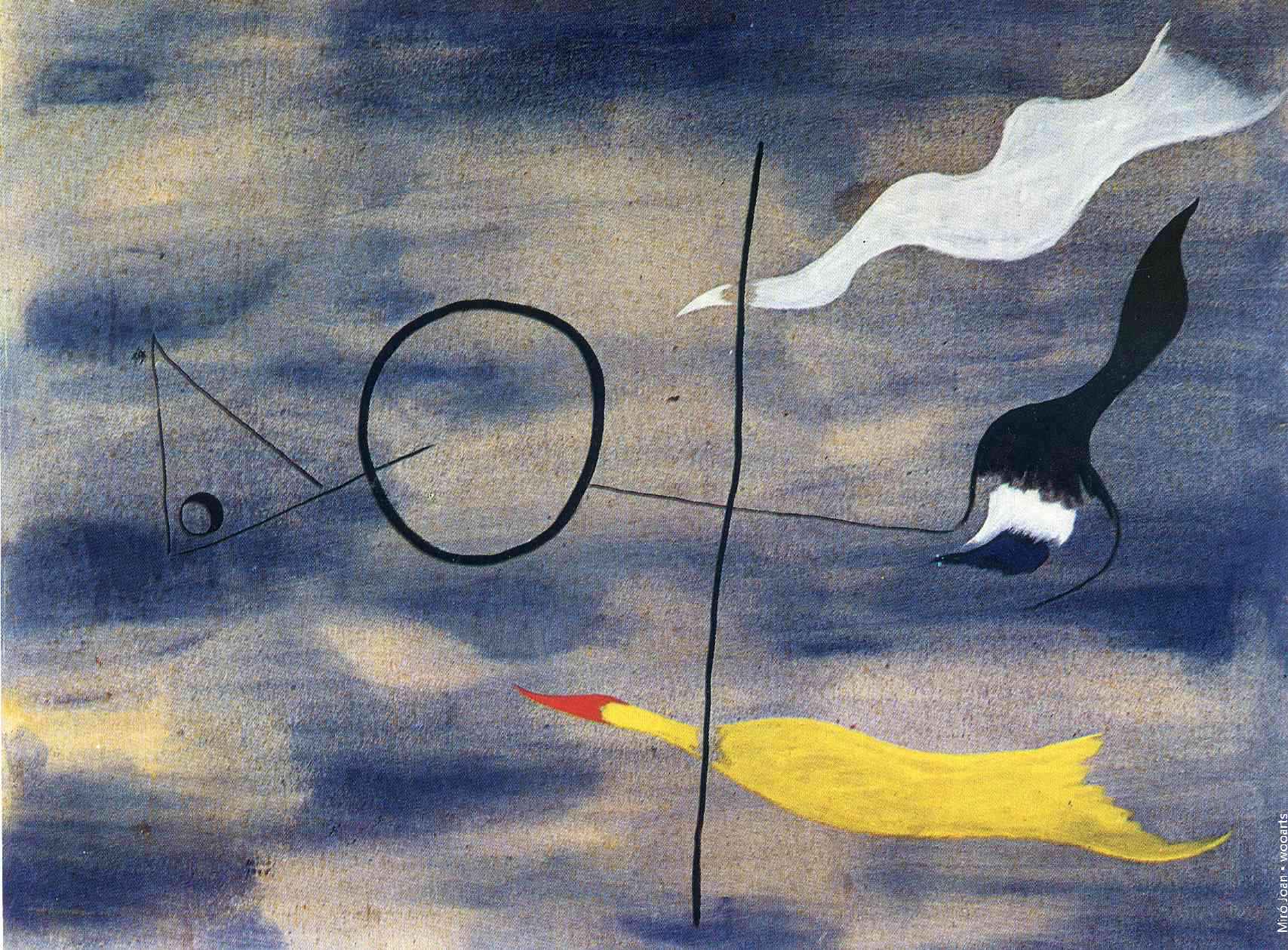

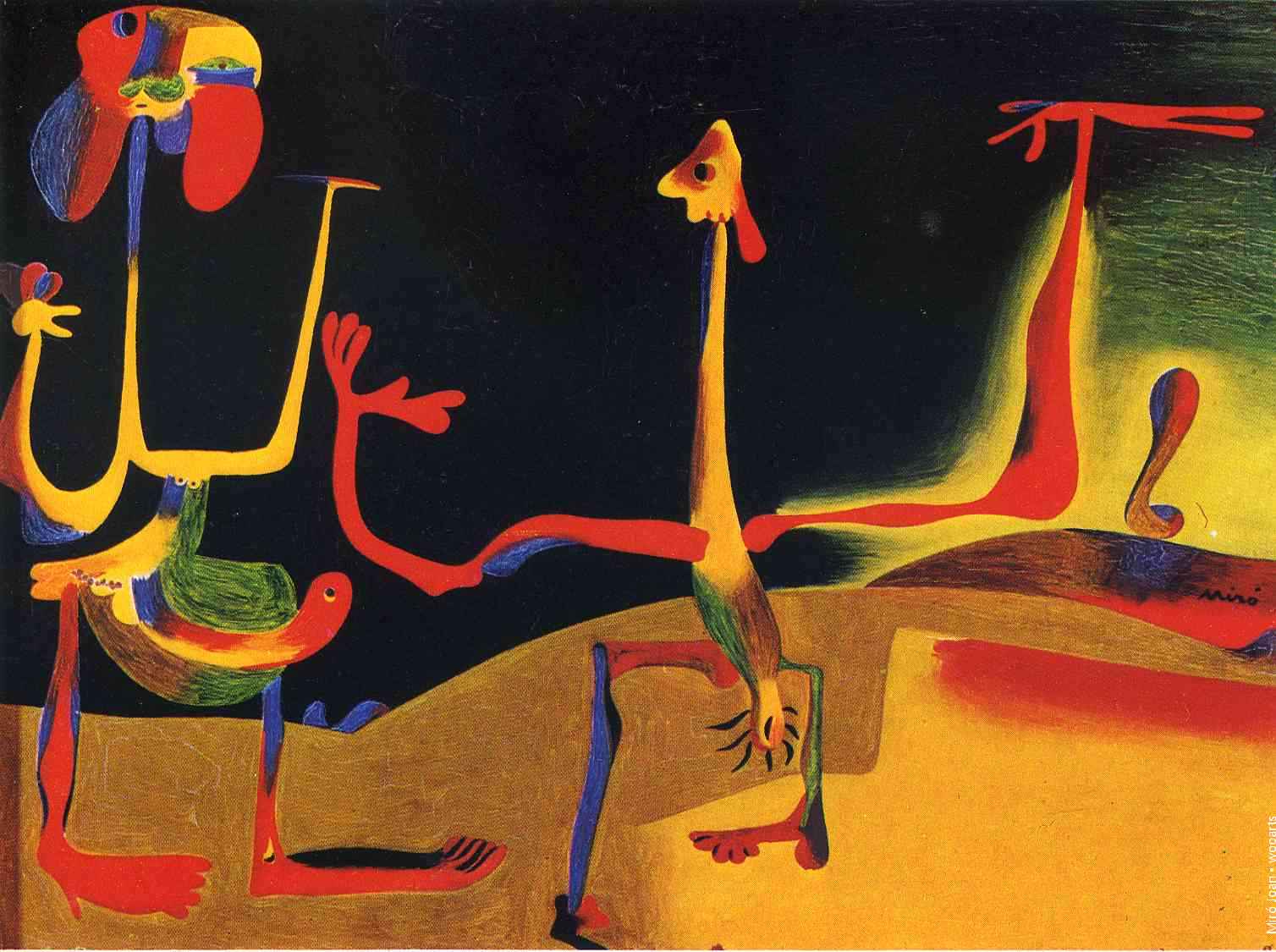

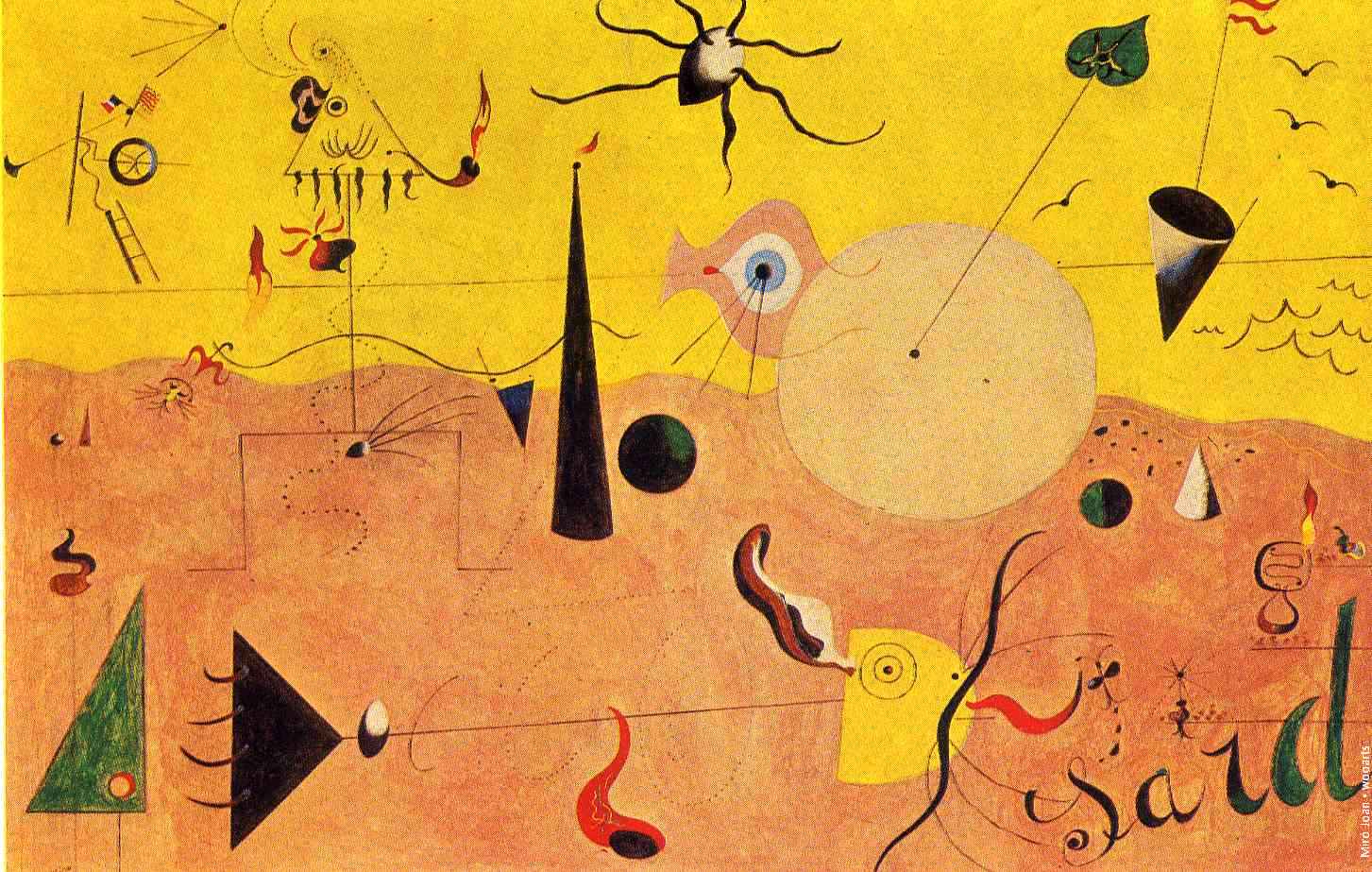

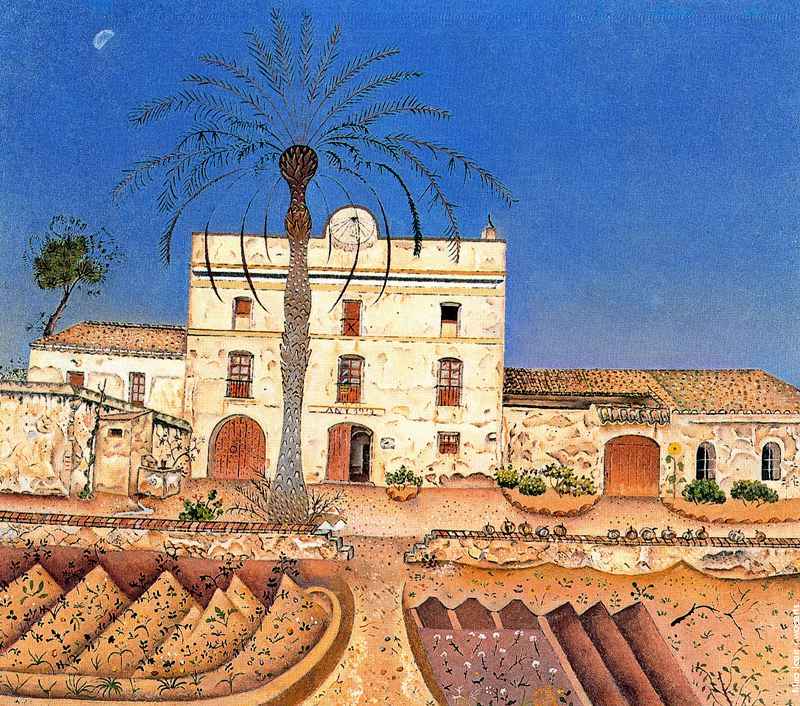

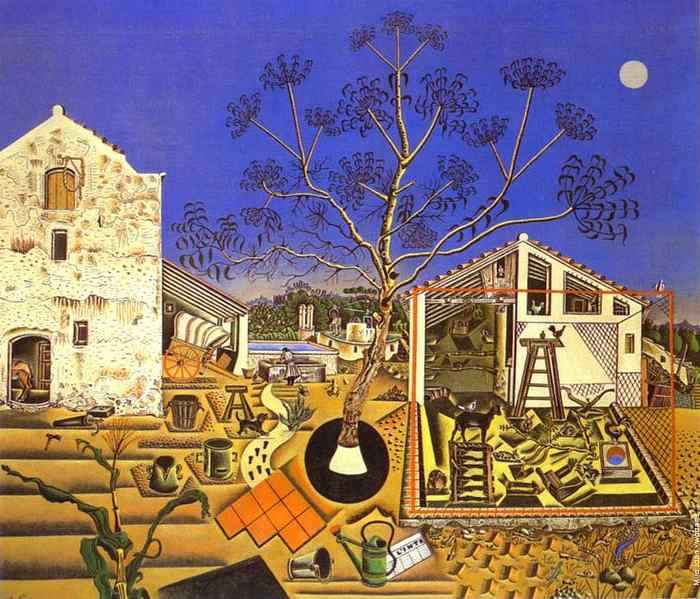

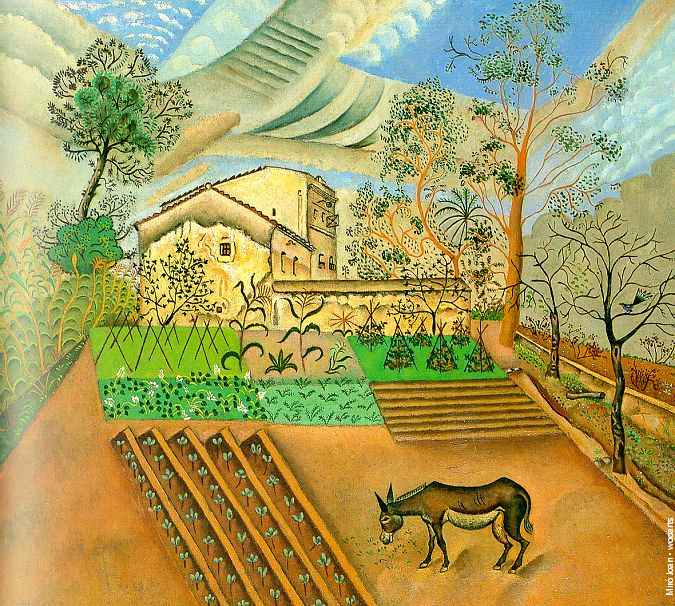

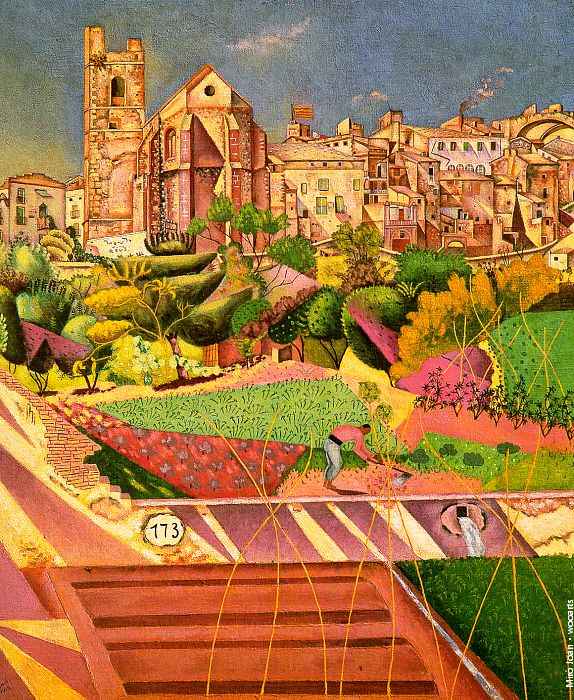

A few years after Miró’s 1918 Barcelona solo exhibition, he settled in Paris where he finished a number of paintings that he had begun on his parents’ summer home and farm in Mont-roig del Camp. One such painting, The Farm, showed a transition to a more individual style of painting and certain nationalistic qualities. Ernest Hemingway, who later purchased the piece, compared the artistic accomplishment to James Joyce’s Ulysses and described it by saying, “It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there. No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things.” Miró annually returned to Mont-roig and developed a symbolism and nationalism that would stick with him throughout his career. Two of Miró’s first works classified as Surrealist, Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) and The Tilled Field, employ the symbolic language that was to dominate the art of the next decade.

Josep Dalmau arranged Miró’s first Parisian solo exhibition, at Galerie la Licorne in 1921.

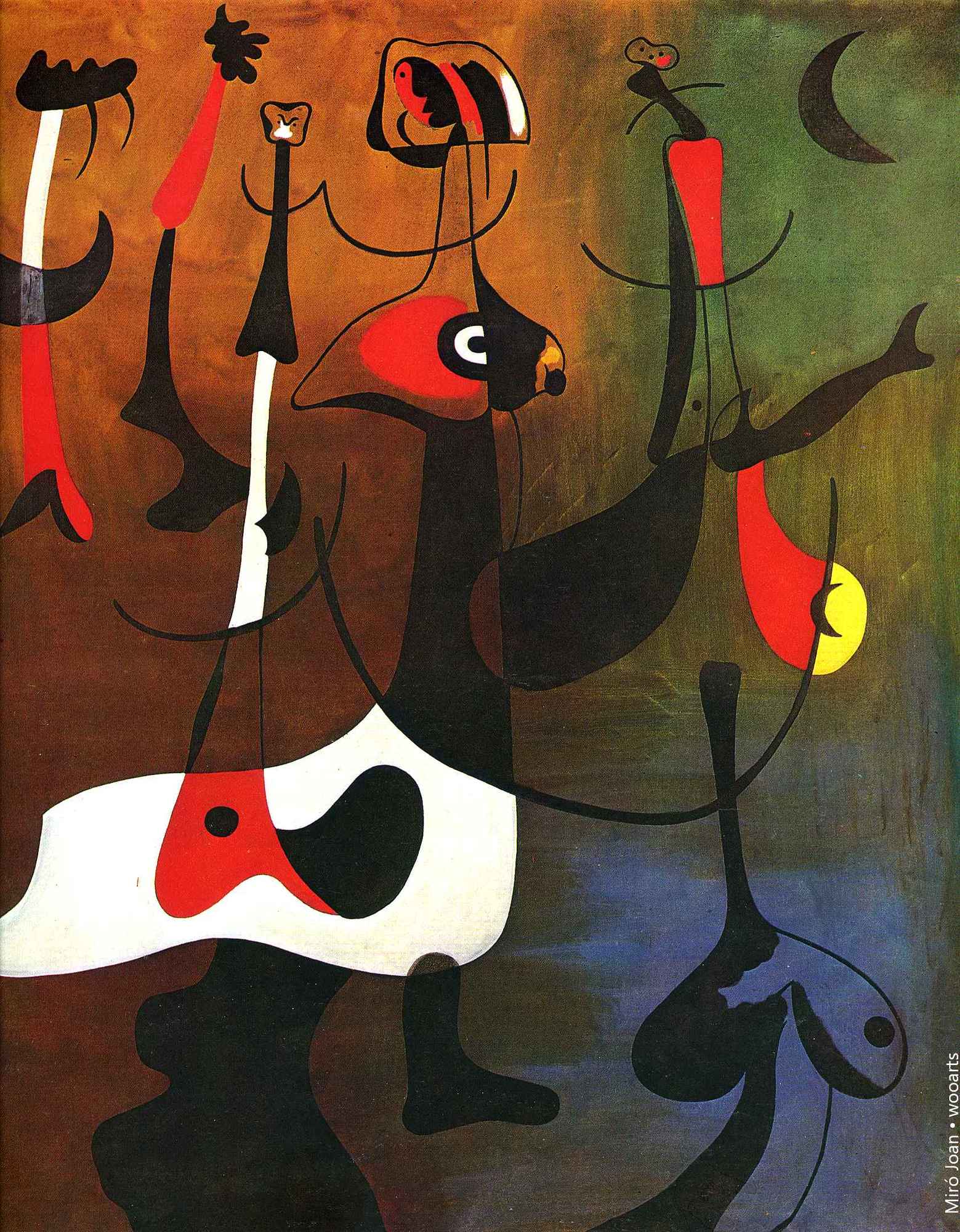

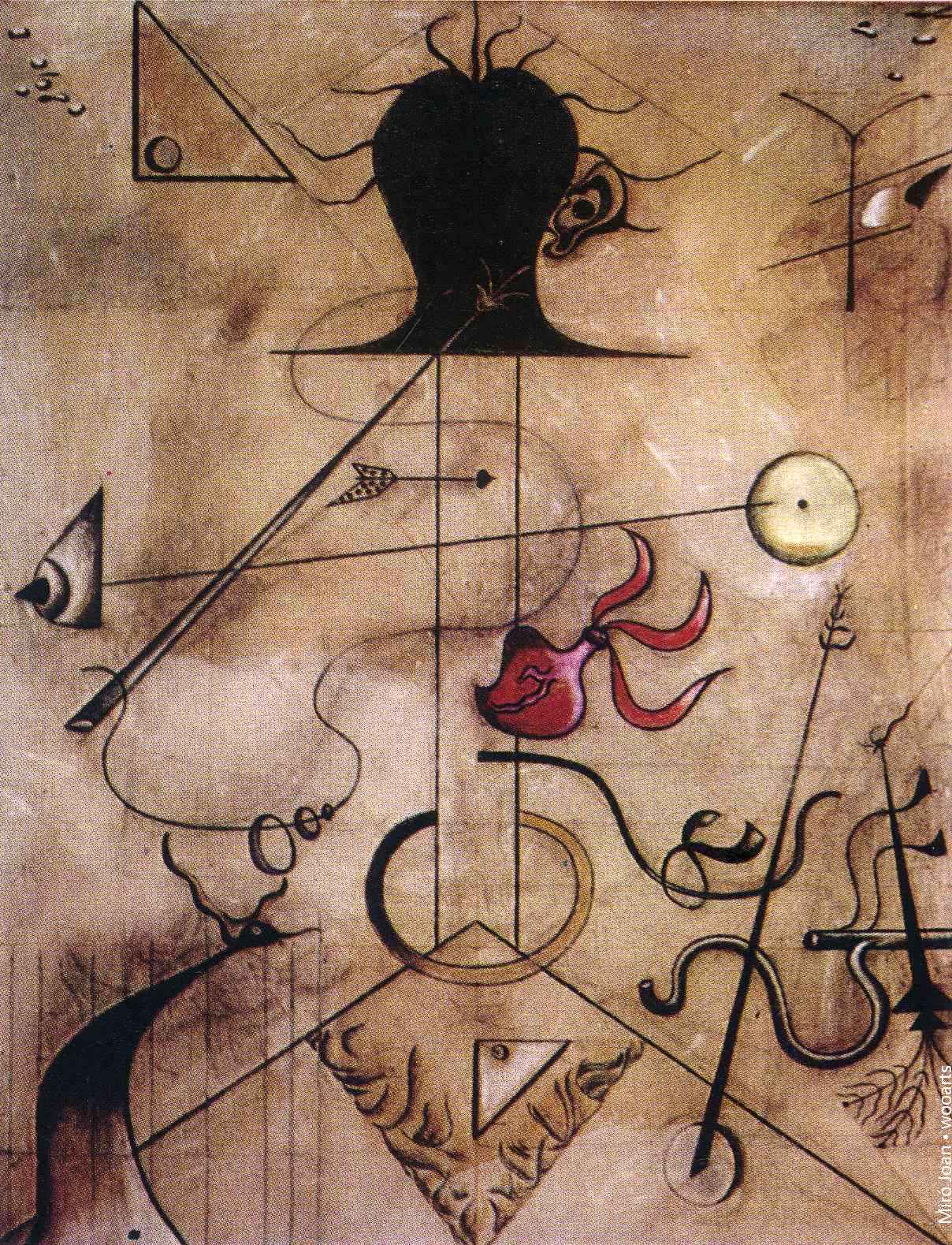

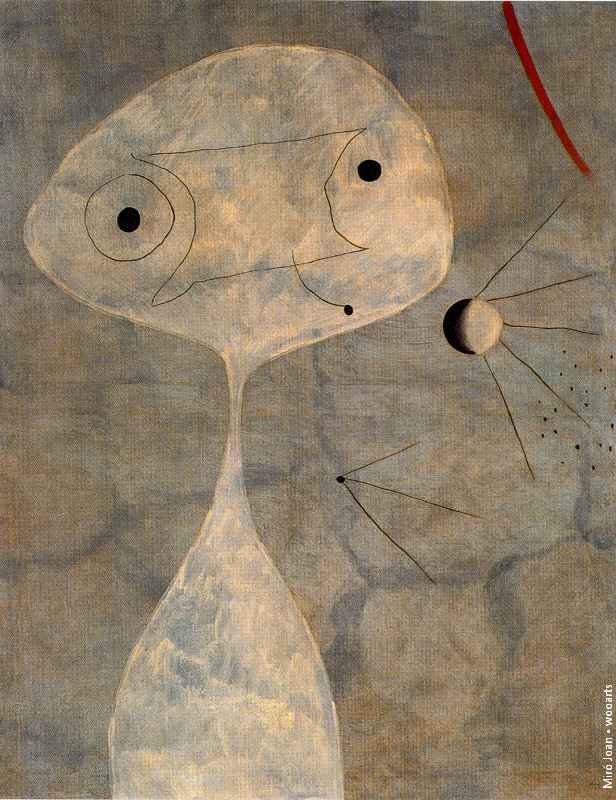

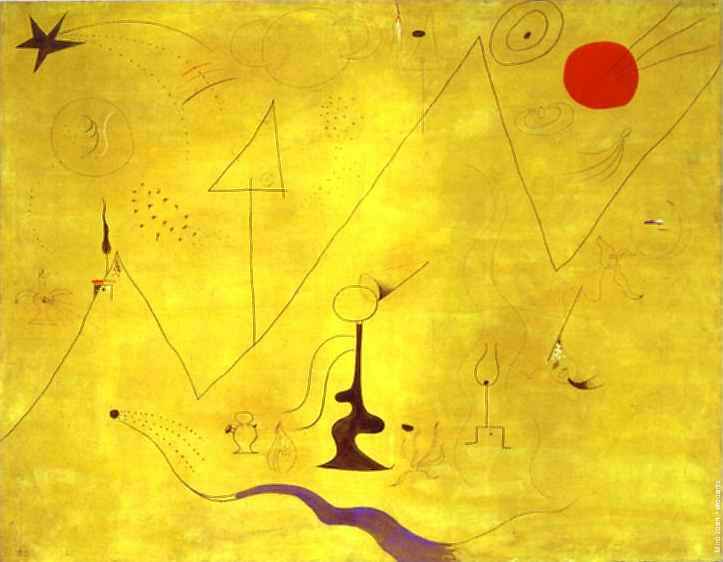

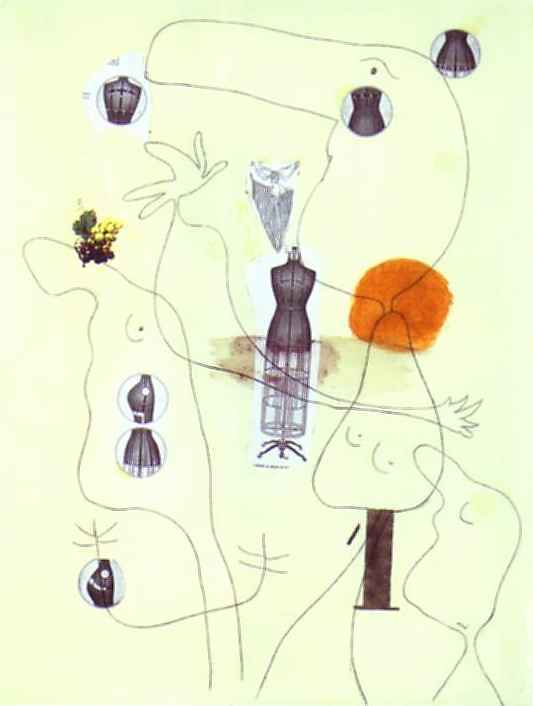

In 1924, Miró joined the Surrealist group. The already symbolic and poetic nature of Miró’s work, as well as the dualities and contradictions inherent to it, fit well within the context of dream-like automatism espoused by the group. Much of Miró’s work lost the cluttered chaotic lack of focus that had defined his work thus far, and he experimented with collage and the process of painting within his work so as to reject the framing that traditional painting provided. This antagonistic attitude towards painting manifested itself when Miró referred to his work in 1924 ambiguously as “x” in a letter to poet friend Michel Leiris. The paintings that came out of this period were eventually dubbed Miró’s dream paintings.

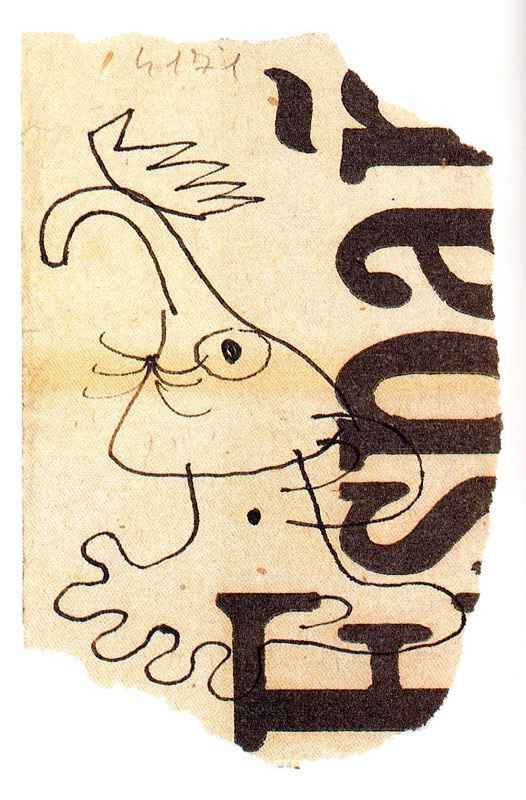

Miró did not completely abandon subject matter, though. Despite the Surrealist automatic techniques that he employed extensively in the 1920s, sketches show that his work was often the result of a methodical process. Miró’s work rarely dipped into non-objectivity, maintaining a symbolic, schematic language. This was perhaps most prominent in the repeated Head of a Catalan Peasant series of 1924 to 1925. In 1926, he collaborated with Max Ernst on designs for ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

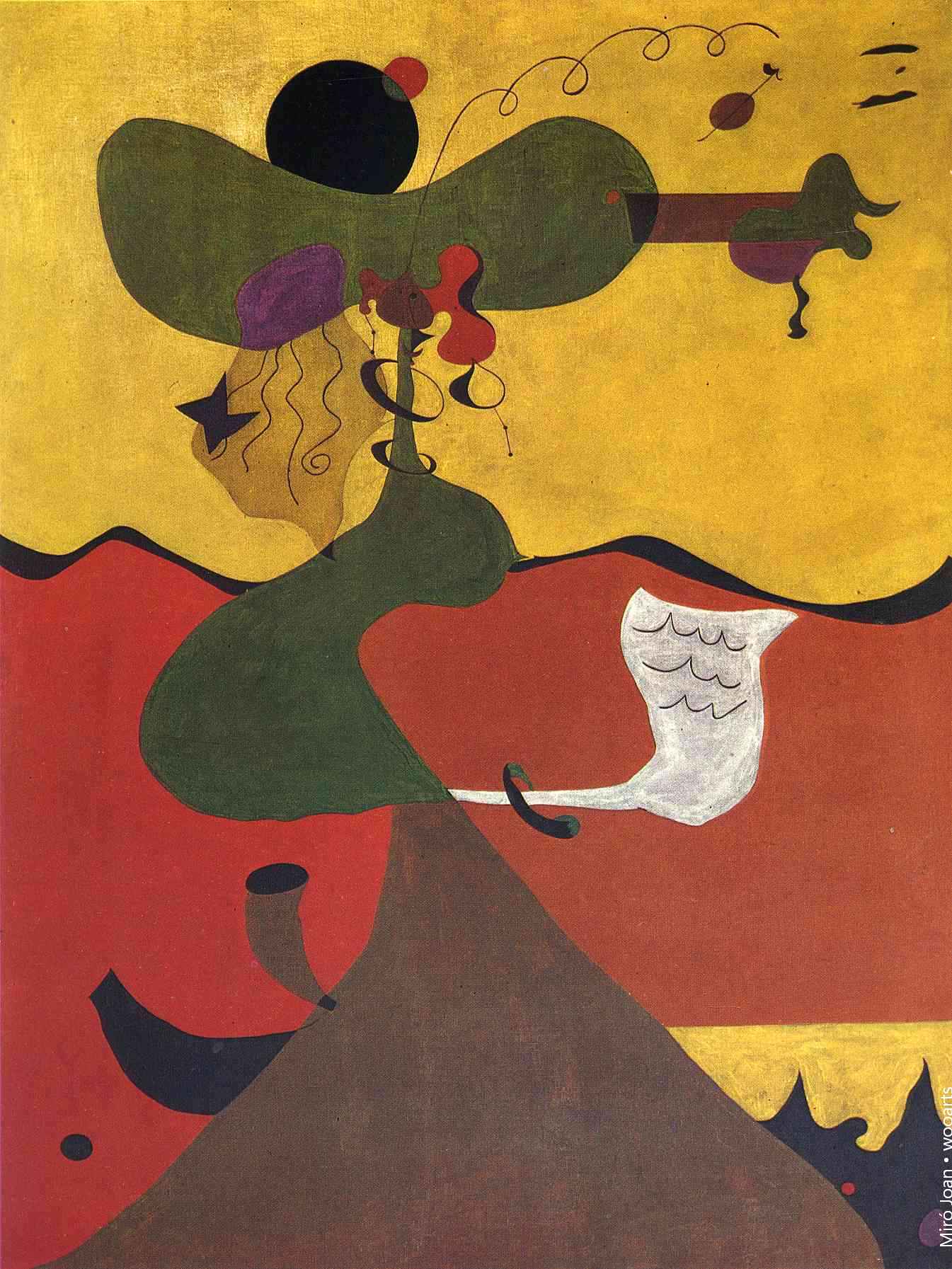

Miró returned to a more representational form of painting with The Dutch Interiors of 1928. Crafted after works by Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh and Jan Steen seen as postcard reproductions, the paintings reveal the influence of a trip to Holland taken by the artist. These paintings share more in common with Tilled Field or Harlequin’s Carnival than with the minimalistic dream paintings produced a few years earlier.

Miró married Pilar Juncosa in Palma (Majorca) on 12 October 1929. Their daughter, María Dolores Miró, was born on 17 July 1930. In 1931, Pierre Matisse opened an art gallery in New York City. The Pierre Matisse Gallery (which existed until Matisse’s death in 1989) became an influential part of the Modern art movement in America. From the outset Matisse represented Joan Miró and introduced his work to the United States market by frequently exhibiting Miró’s work in New York.

Until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Miró habitually returned to Spain in the summers. Once the war began, he was unable to return home. Unlike many of his surrealist contemporaries, Miró had previously preferred to stay away from explicitly political commentary in his work. Though a sense of (Catalan) nationalism pervaded his earliest surreal landscapes and Head of a Catalan Peasant, it was not until Spain’s Republican government commissioned him to paint the mural The Reaper, for the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exhibition, that Miró’s work took on a politically charged meaning.

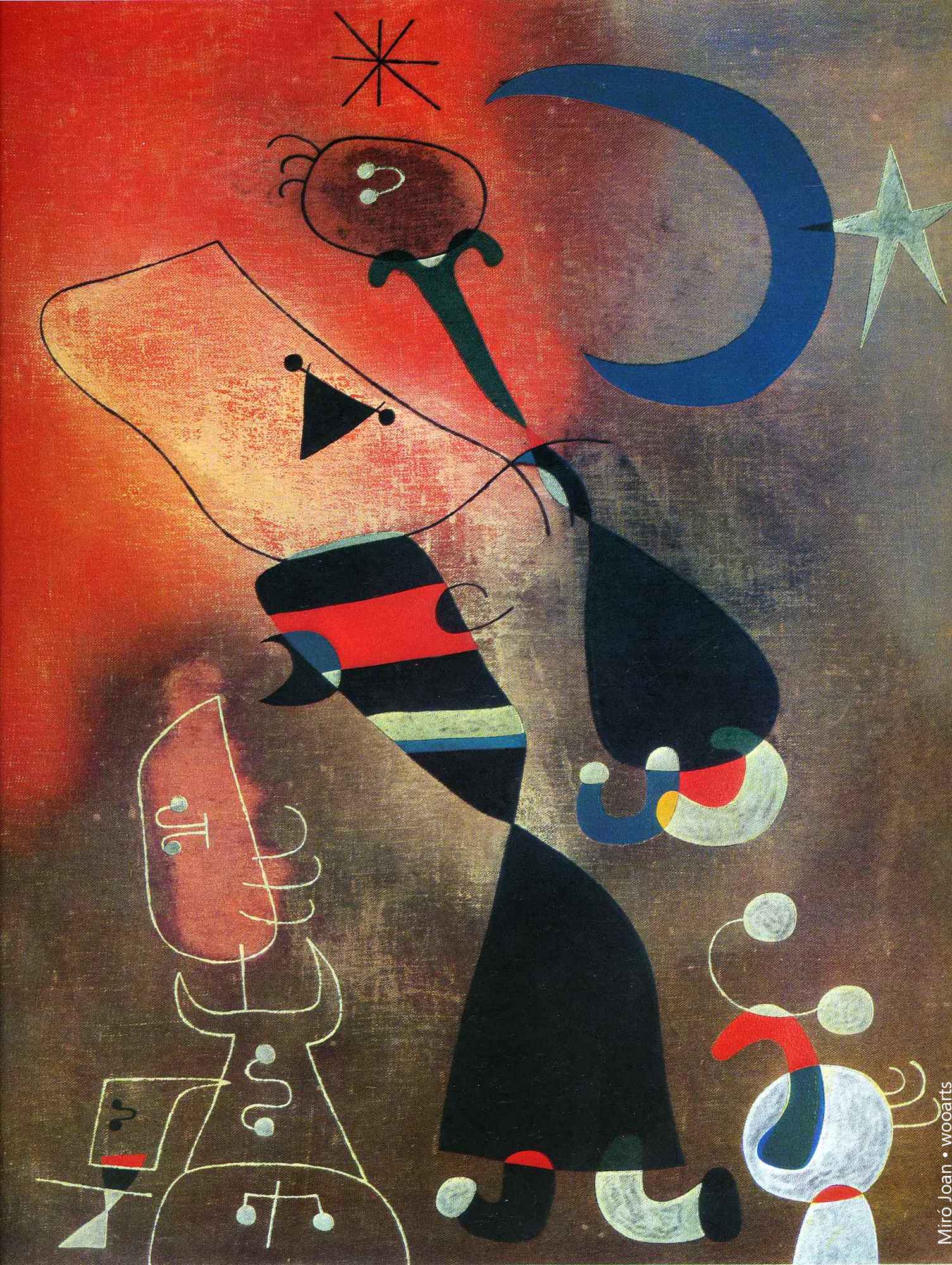

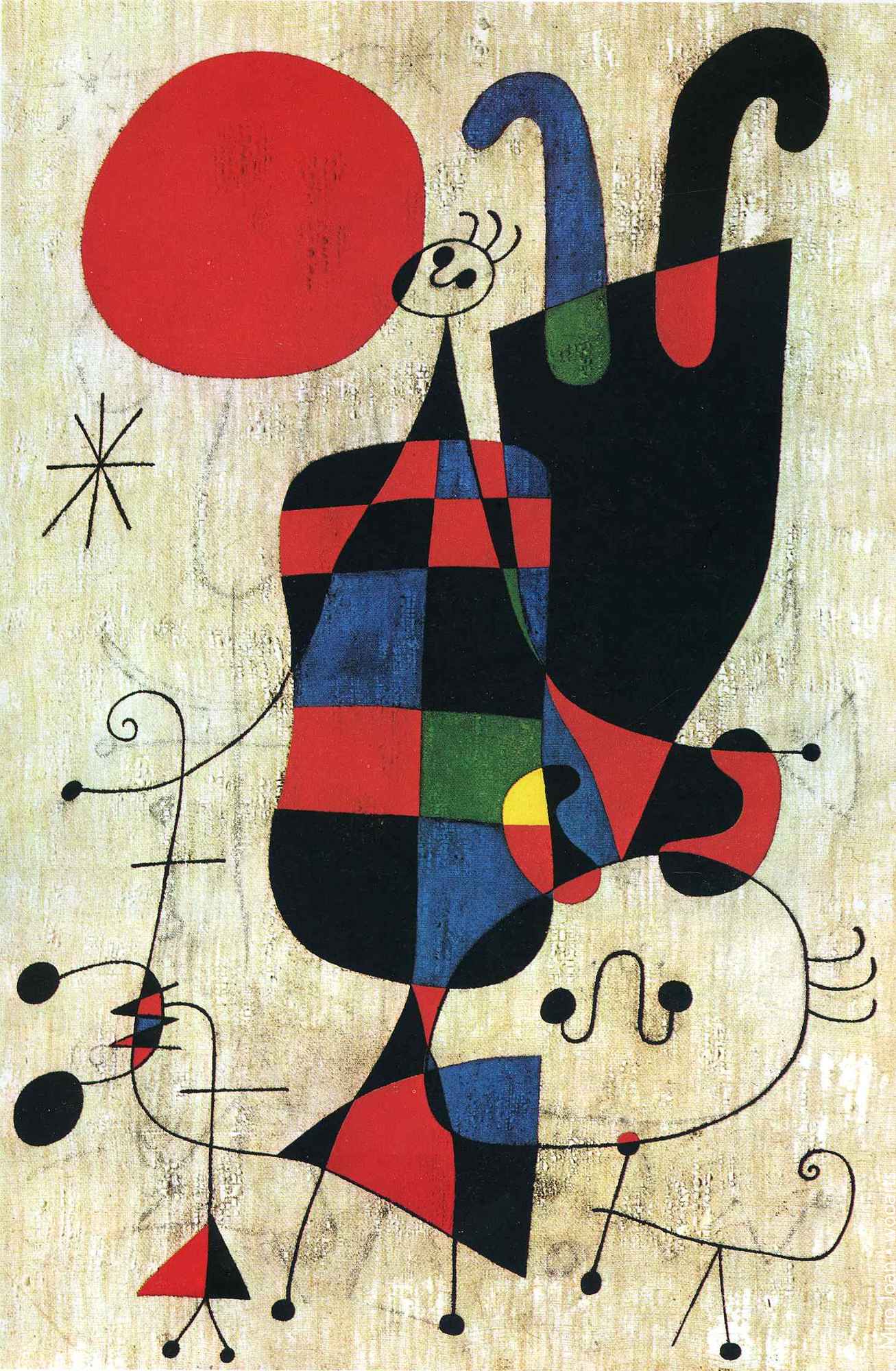

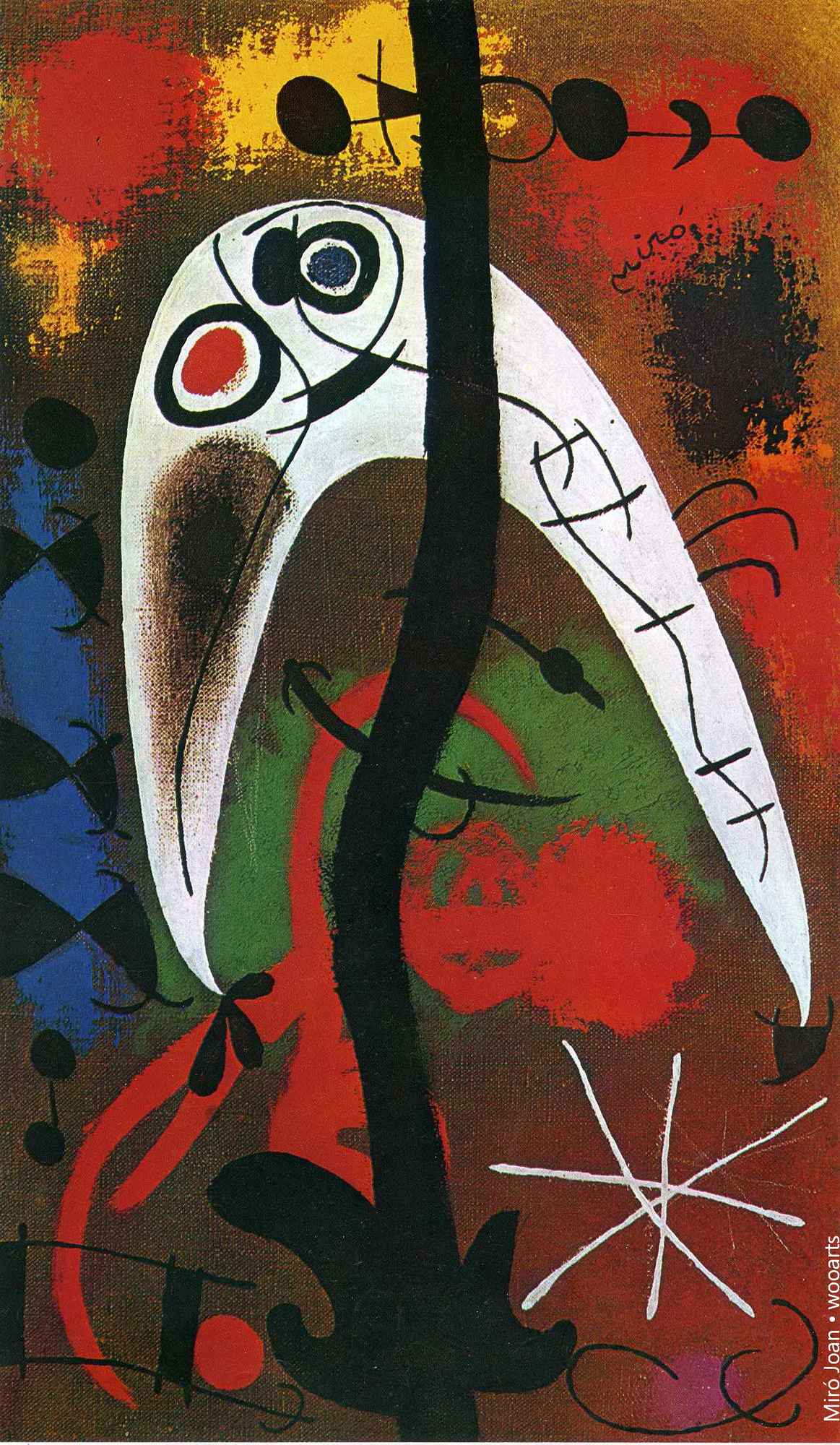

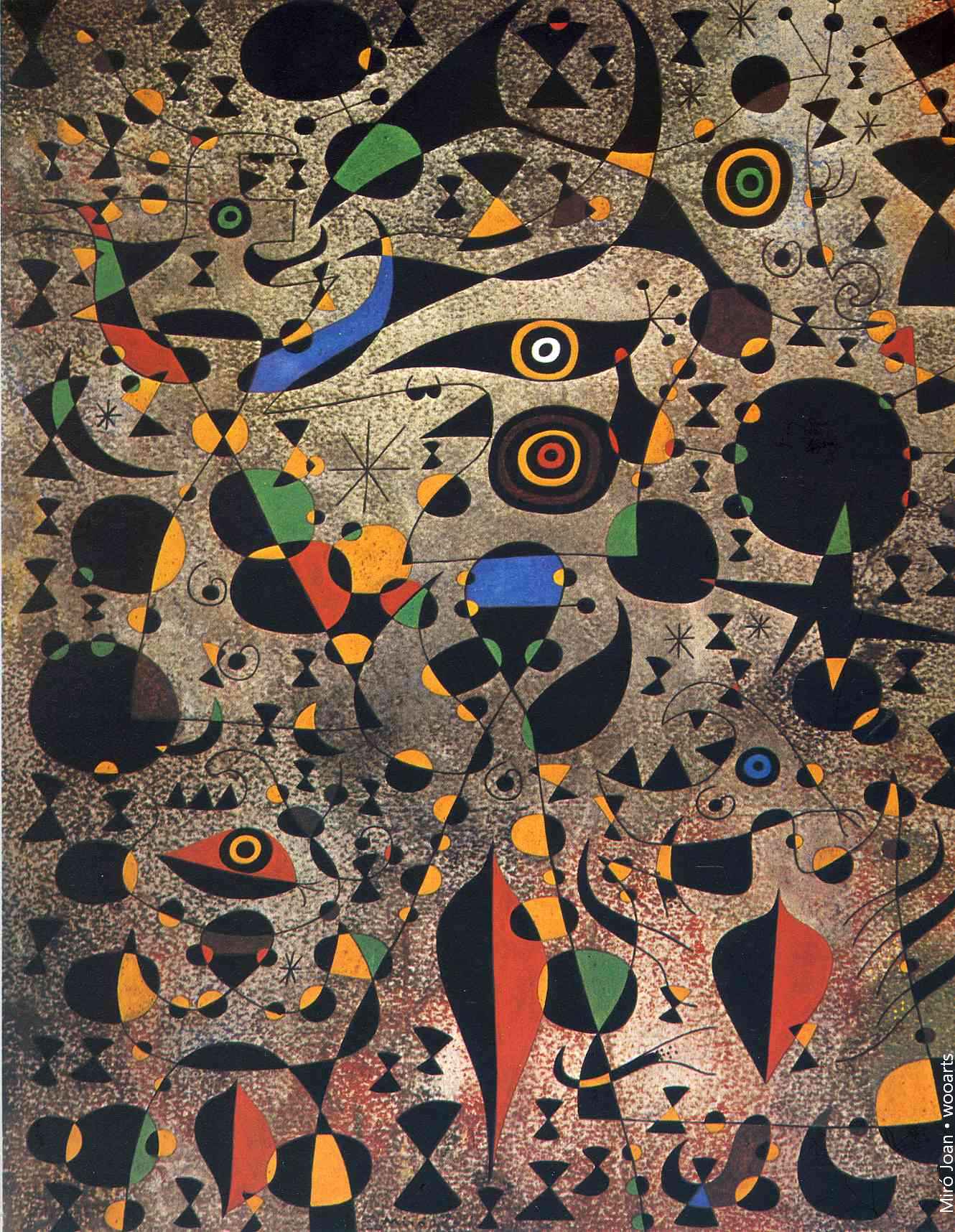

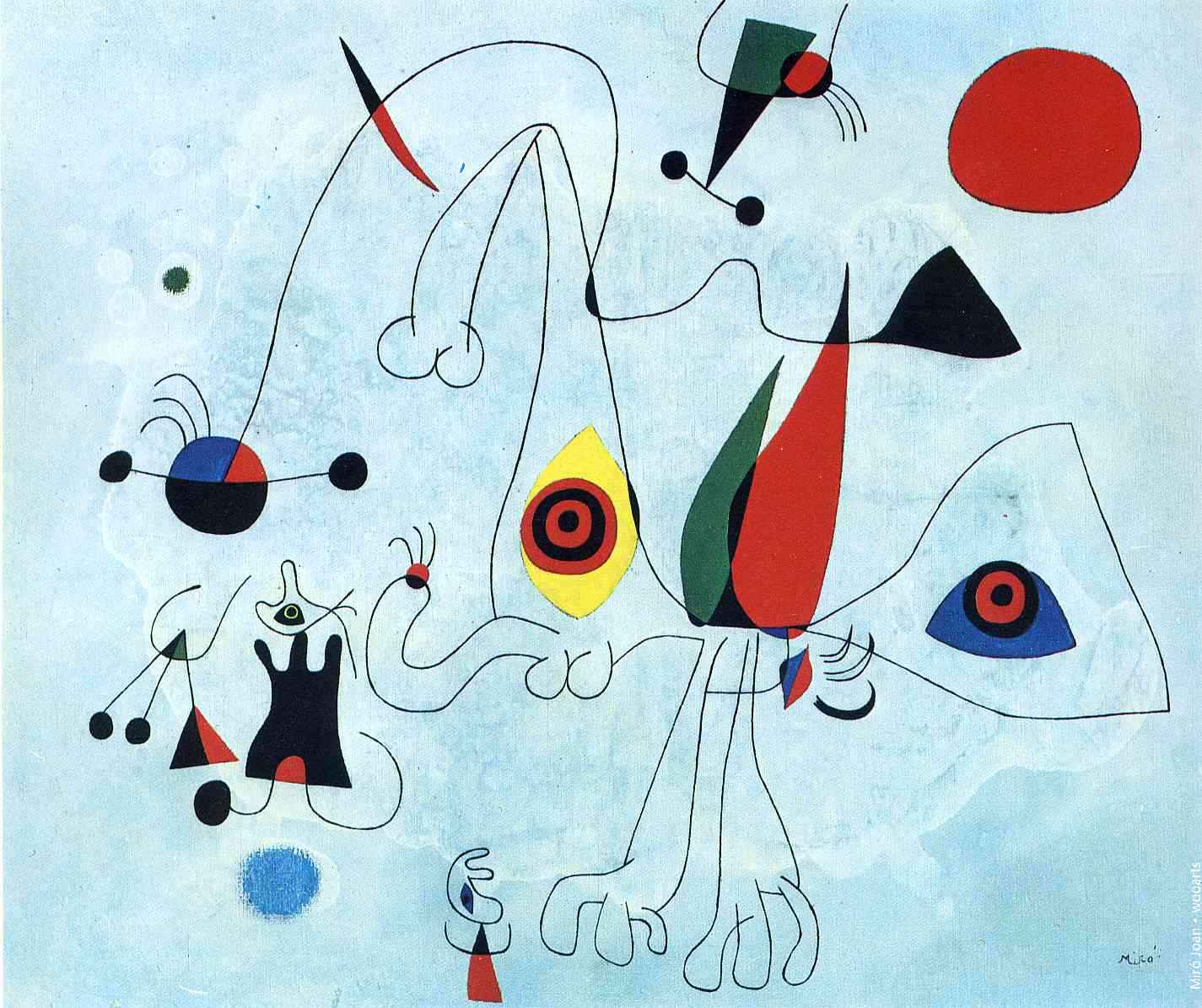

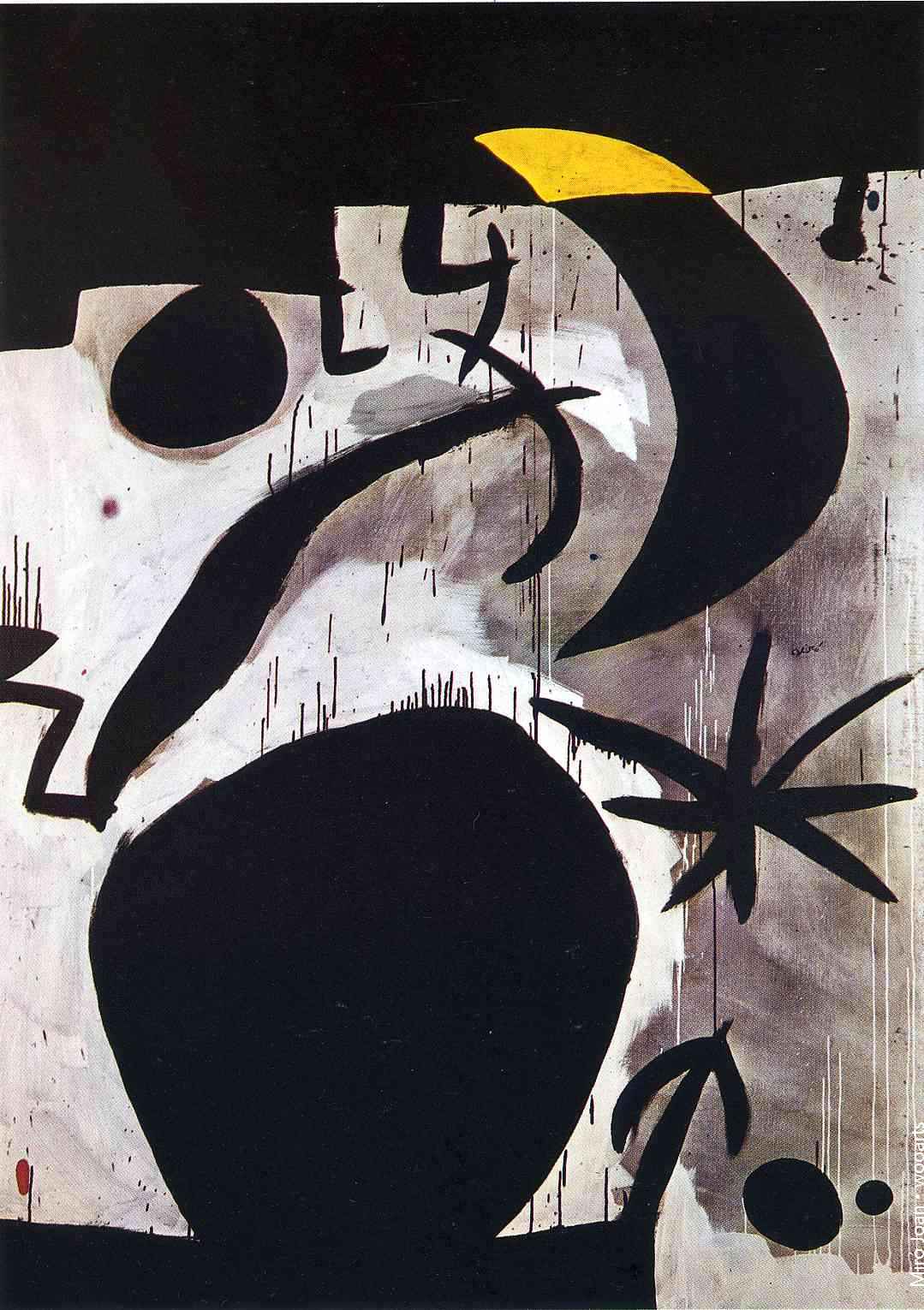

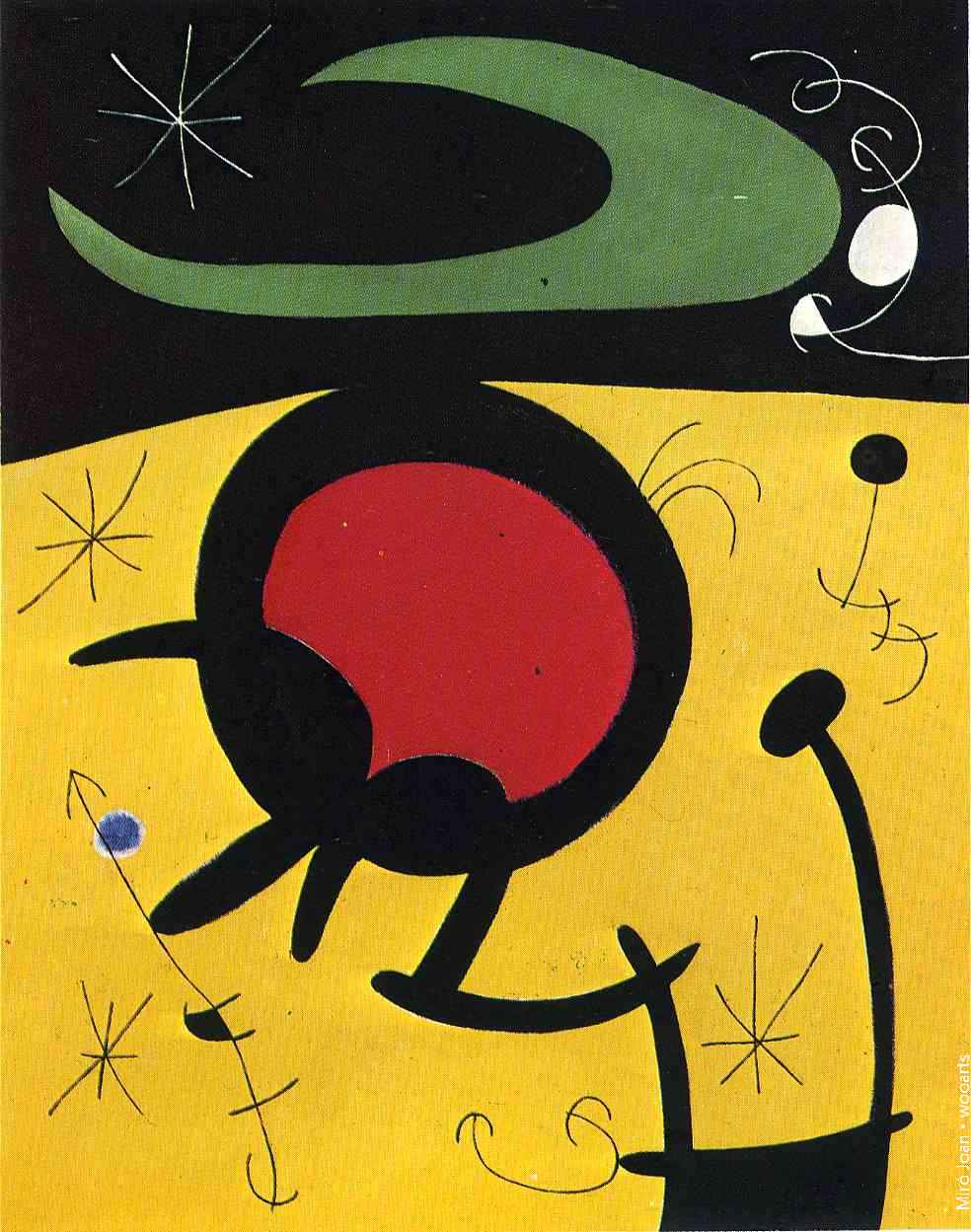

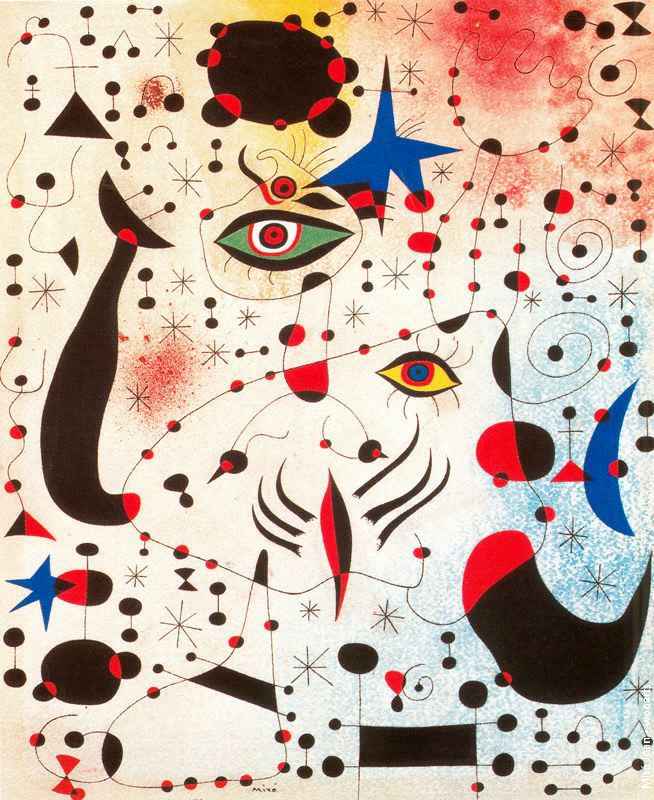

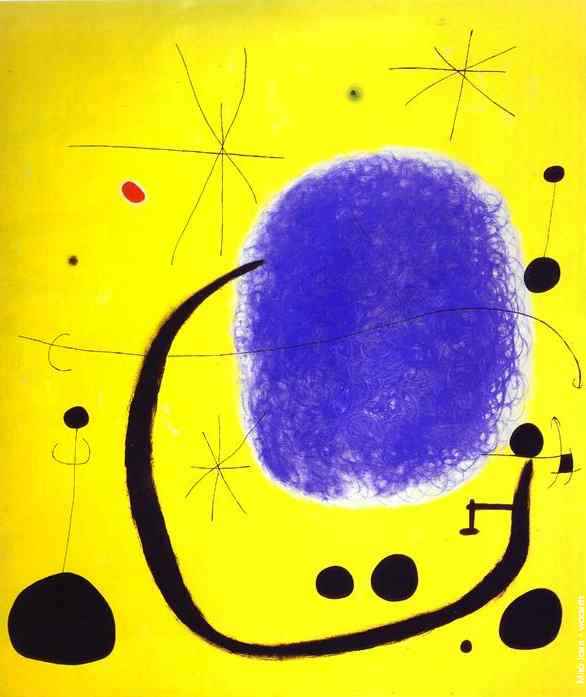

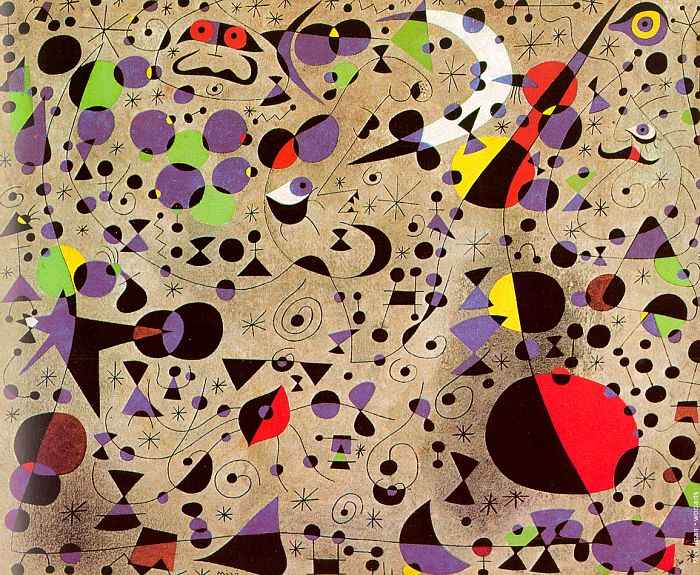

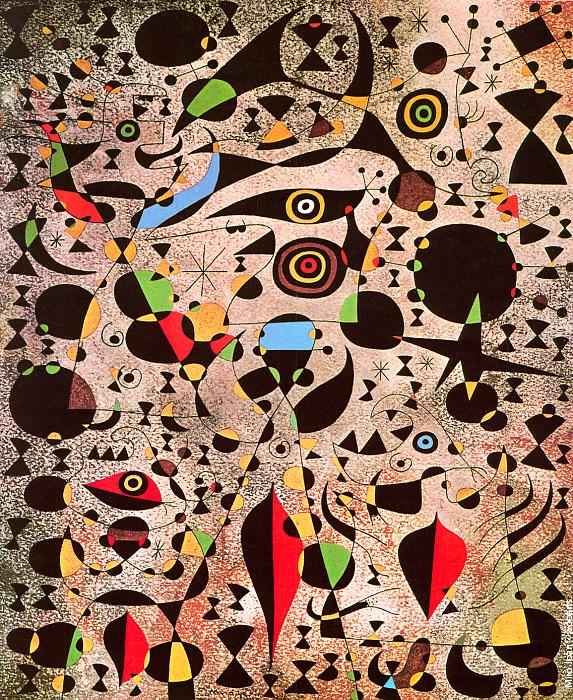

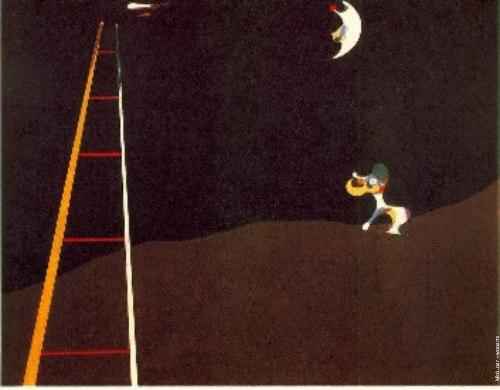

In 1939, with Germany’s invasion of France looming, Miró relocated to Varengeville in Normandy, and on 20 May of the following year, as Germans invaded Paris, he narrowly fled to Spain (now controlled by Francisco Franco) for the duration of the Vichy Regime’s rule. In Varengeville, Palma, and Mont-roig, between 1940 and 1941, Miró created the twenty-three gouache series Constellations. Revolving around celestial symbolism, Constellations earned the artist praise from André Breton, who seventeen years later wrote a series of poems, named after and inspired by Miró’s series. Features of this work revealed a shifting focus to the subjects of women, birds, and the moon, which would dominate his iconography for much of the rest of his career.

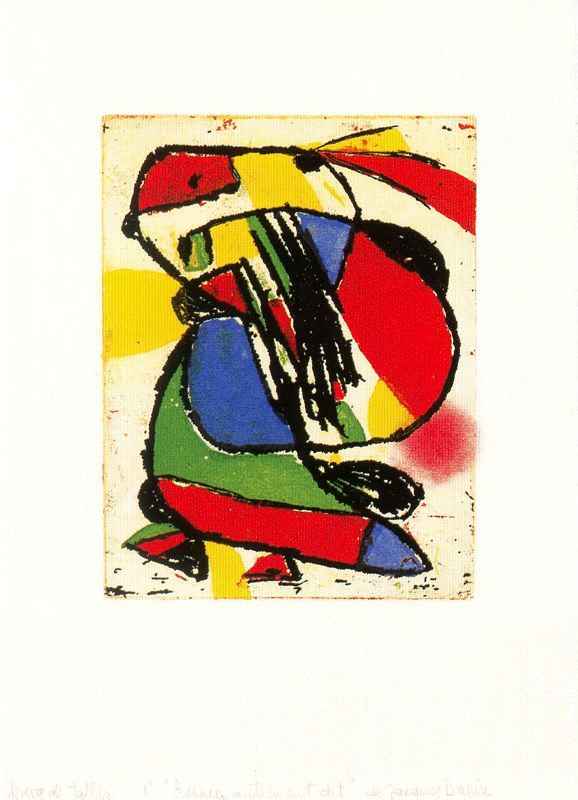

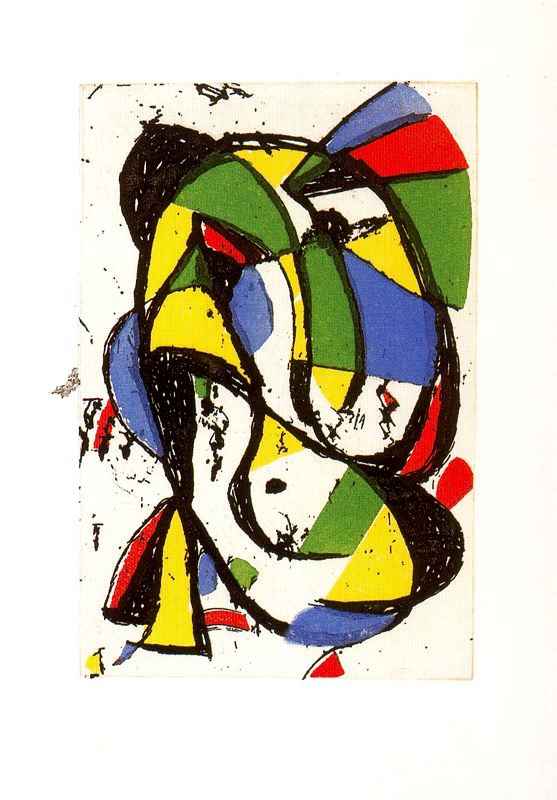

Shuzo Takiguchi published the first monograph on Miró in 1940. In 1948–49 Miró lived in Barcelona and made frequent visits to Paris to work on printing techniques at the Mourlot Studios and the Atelier Lacourière. He developed a close relationship with Fernand Mourlot and that resulted in the production of over one thousand different lithographic editions.

In 1959, André Breton asked Miró to represent Spain in The Homage to Surrealism exhibition alongside Enrique Tábara, Salvador Dalí, and Eugenio Granell. Miró created a series of sculptures and ceramics for the garden of the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, which was completed in 1964.

In 1974, Miró created a tapestry for the World Trade Center in New York City together with the Catalan artist Josep Royo. He had initially refused to do a tapestry, then he learned the craft from Royo and the two artists produced several works together. His World Trade Center Tapestry was displayed at the building and was one of the most expensive works of art lost during the September 11 attacks.

In 1977, Miró and Royo finished a tapestry to be exhibited in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

In 1981, Miró’s The Sun, the Moon and One Star—later renamed Miró’s Chicago—was unveiled. This large, mixed media sculpture is situated outdoors in the downtown Loop area of Chicago, across the street from another large public sculpture, the Chicago Picasso. Miró had created a bronze model of The Sun, the Moon and One Star in 1967. The maquette now resides in the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Late life and death

In 1979 Miró received a doctorate honoris causa from the University of Barcelona. The artist, who suffered from heart failure, died in his home in Palma (Majorca) on 25 December 1983. He was later interred in the Montjuïc Cemetery in Barcelona.

Mental health

It has been established through the analysis of personal texts written by Joan Miró that he has experienced multiple episodes of depression throughout his life. He experienced his first depression when he was 18 in 1911. Much of the literature refers to this as if it was a small setback in his life, while it appeared to be much more than that. Miro himself stated: ‘’I was demoralized and suffered from a serious depression. I fell really ill, and stayed three months in bed’’.

There is a clear connection between his mental health and his paintings, since he used painting as a way of dealing with his episodes of depression. It supposedly even made him more calm and his thoughts less dark. Joan Miró said that without painting he became ‘‘very depressed, gloomy and I get ‘black ideas’, and I do not know what to do with myself’’.

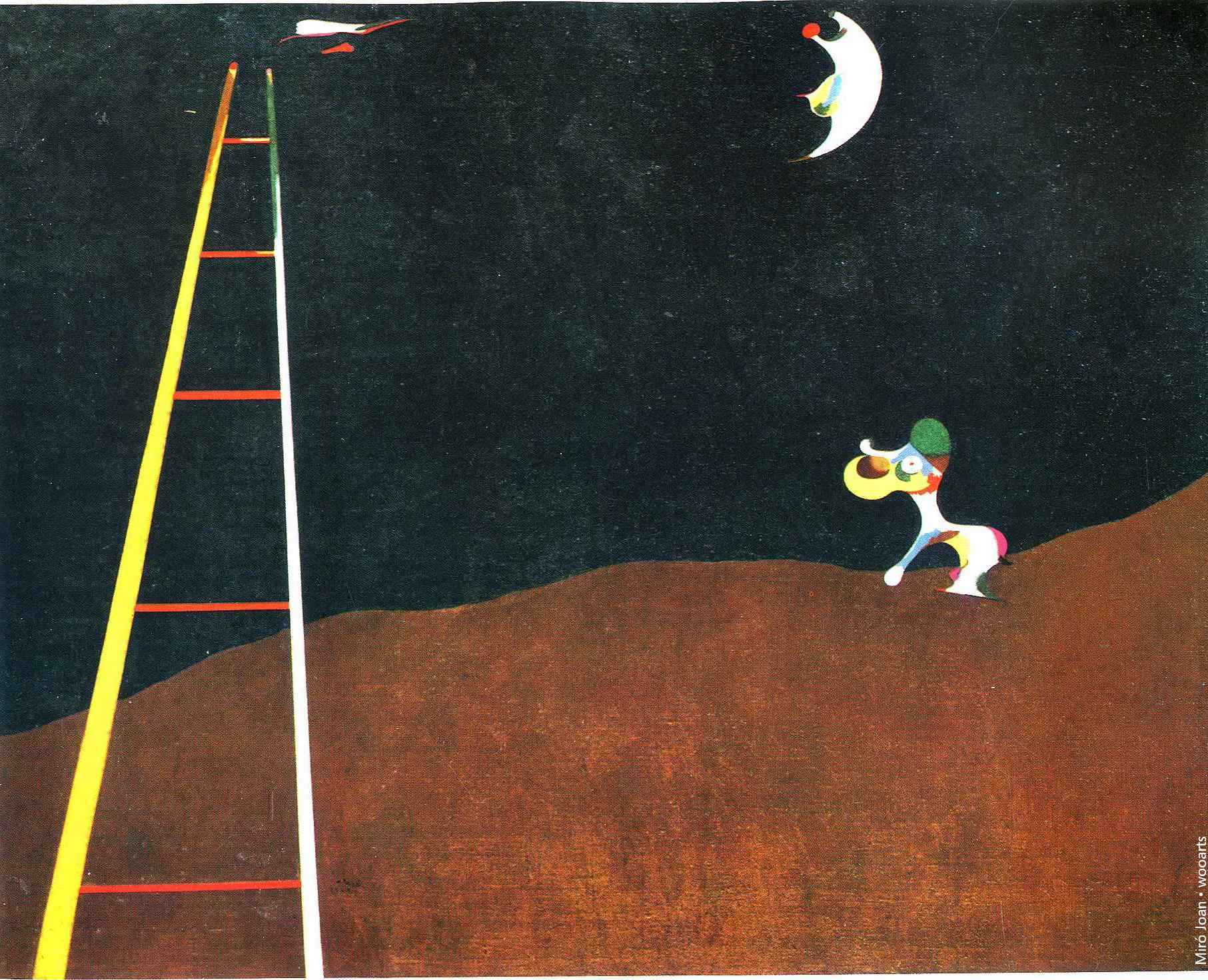

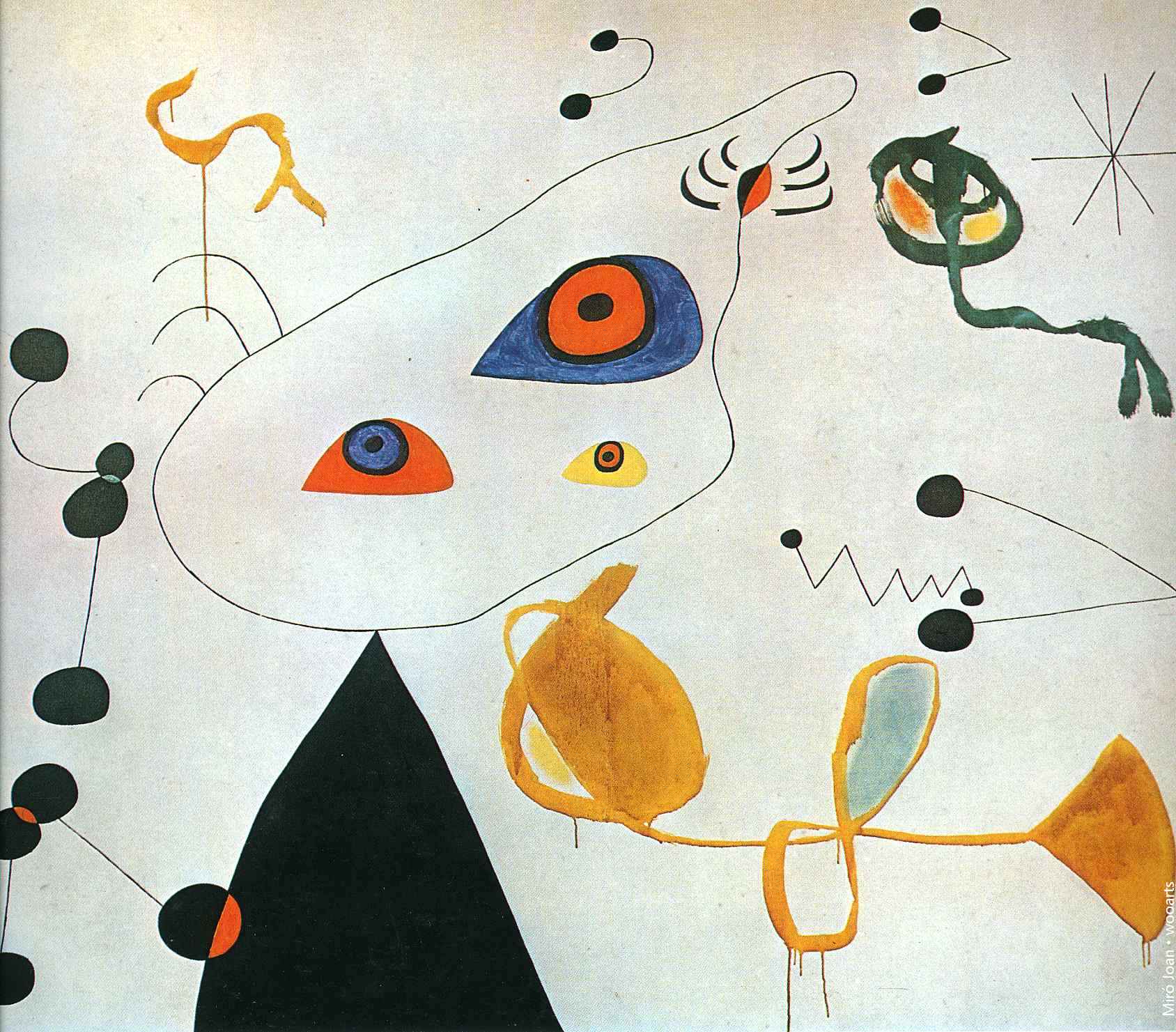

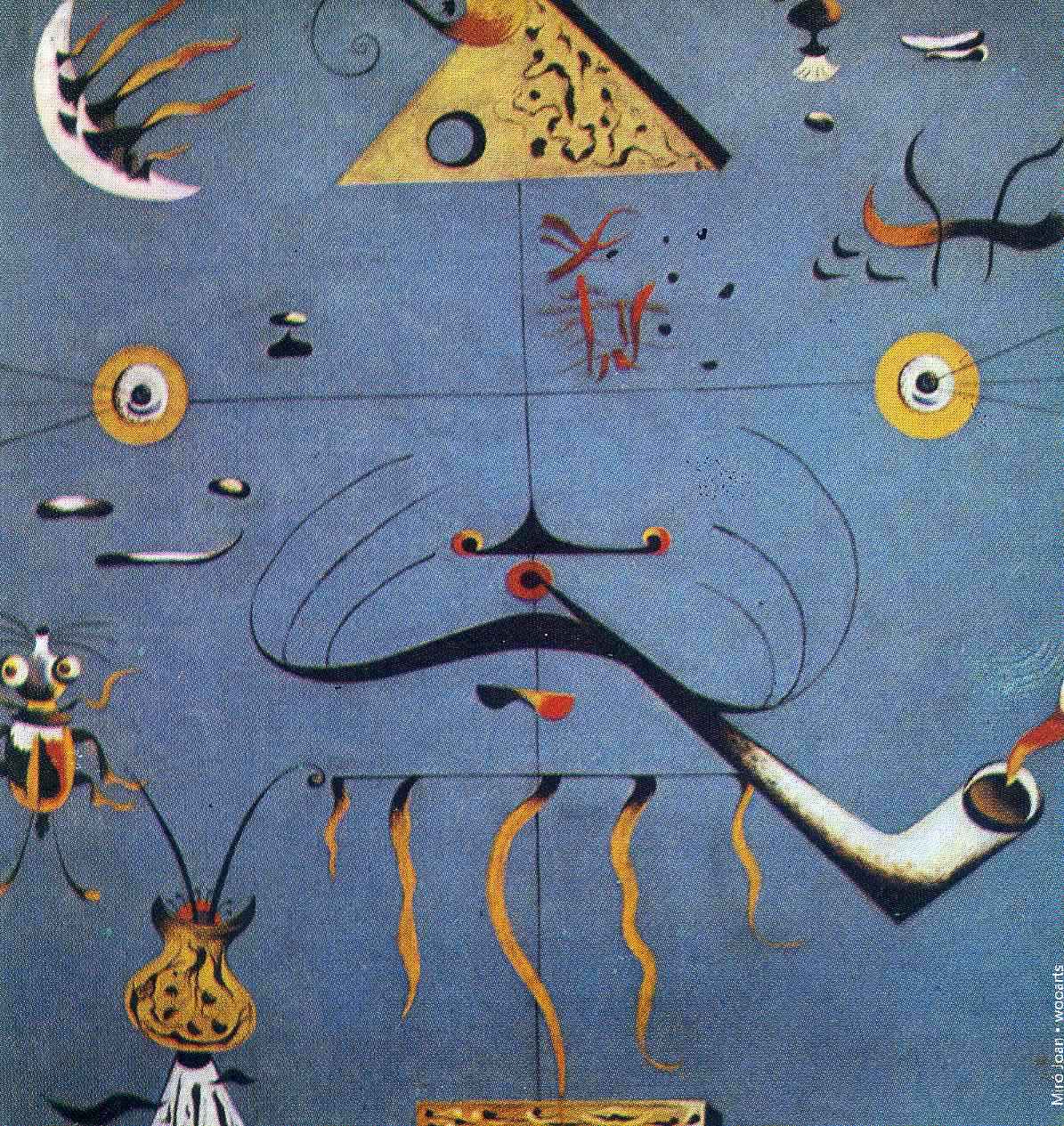

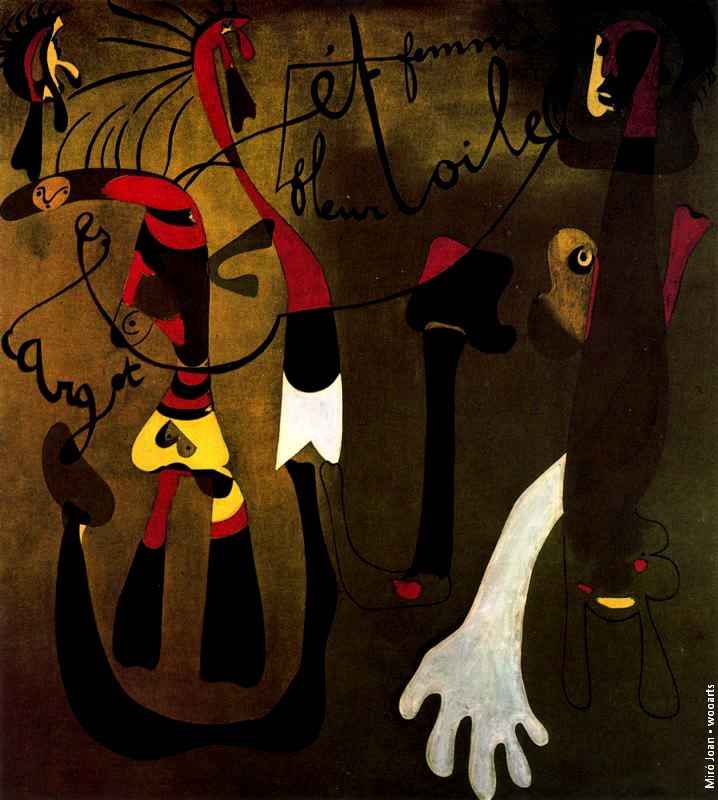

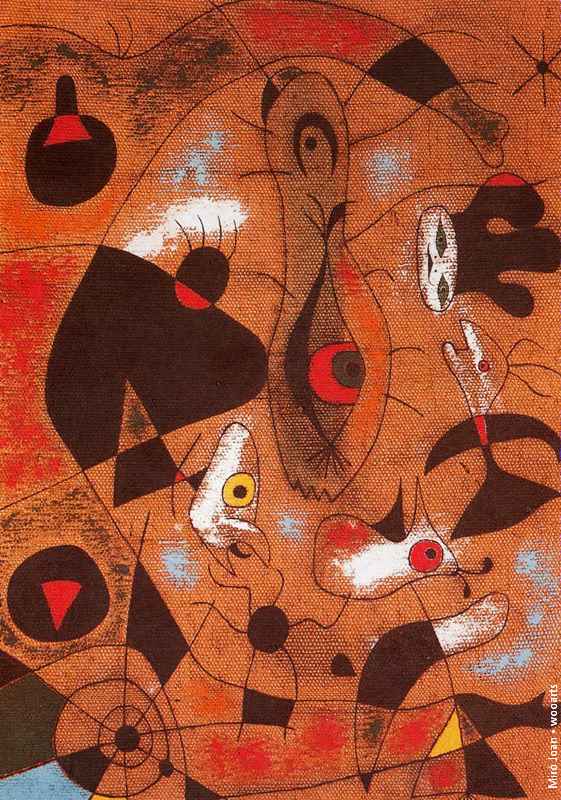

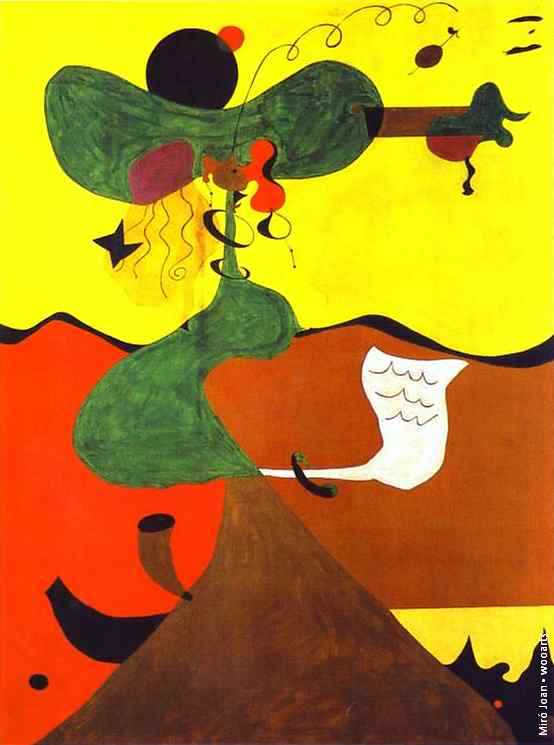

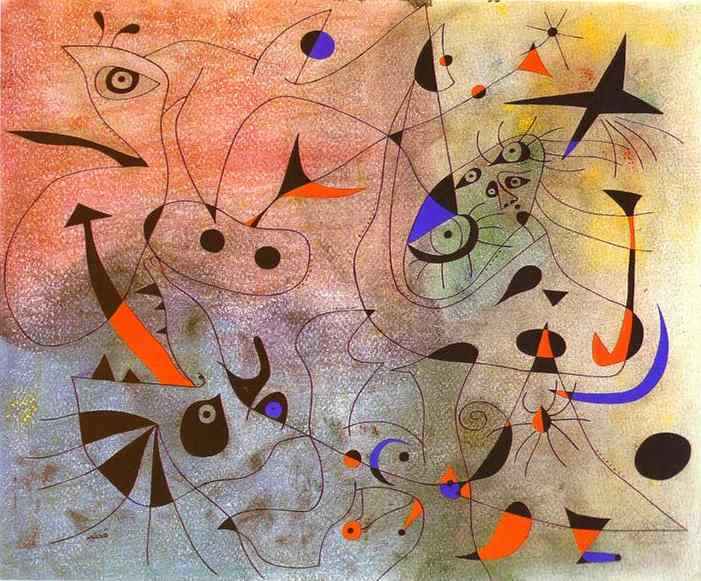

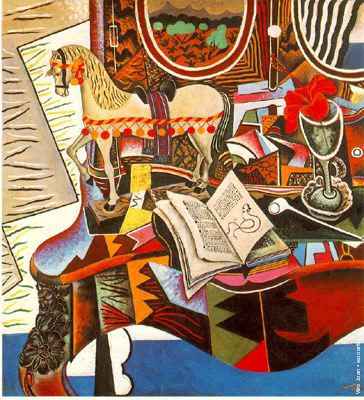

The influence of his mental state is very well visible in his painting Carnival of the Harlequin. He tried to paint the chaos he experienced in his mind, the desperation of wanting to leave that chaos behind and the pain created because of that. Miró painted the symbol of the ladder here which is also visible in multiple other paintings after this painting. It is supposed to symbolize escaping.

The relation between creativity and mental illness is very well studied. Creative people have higher chances of suffering from a manic depressive illness or schizophrenia, as well as higher chance to transmit this genetically. Even though we know Miró suffered from episodic depression, it is uncertain whether he also experienced manic episodes, which is often referred to as bipolar disorder.

via: Wikipedia

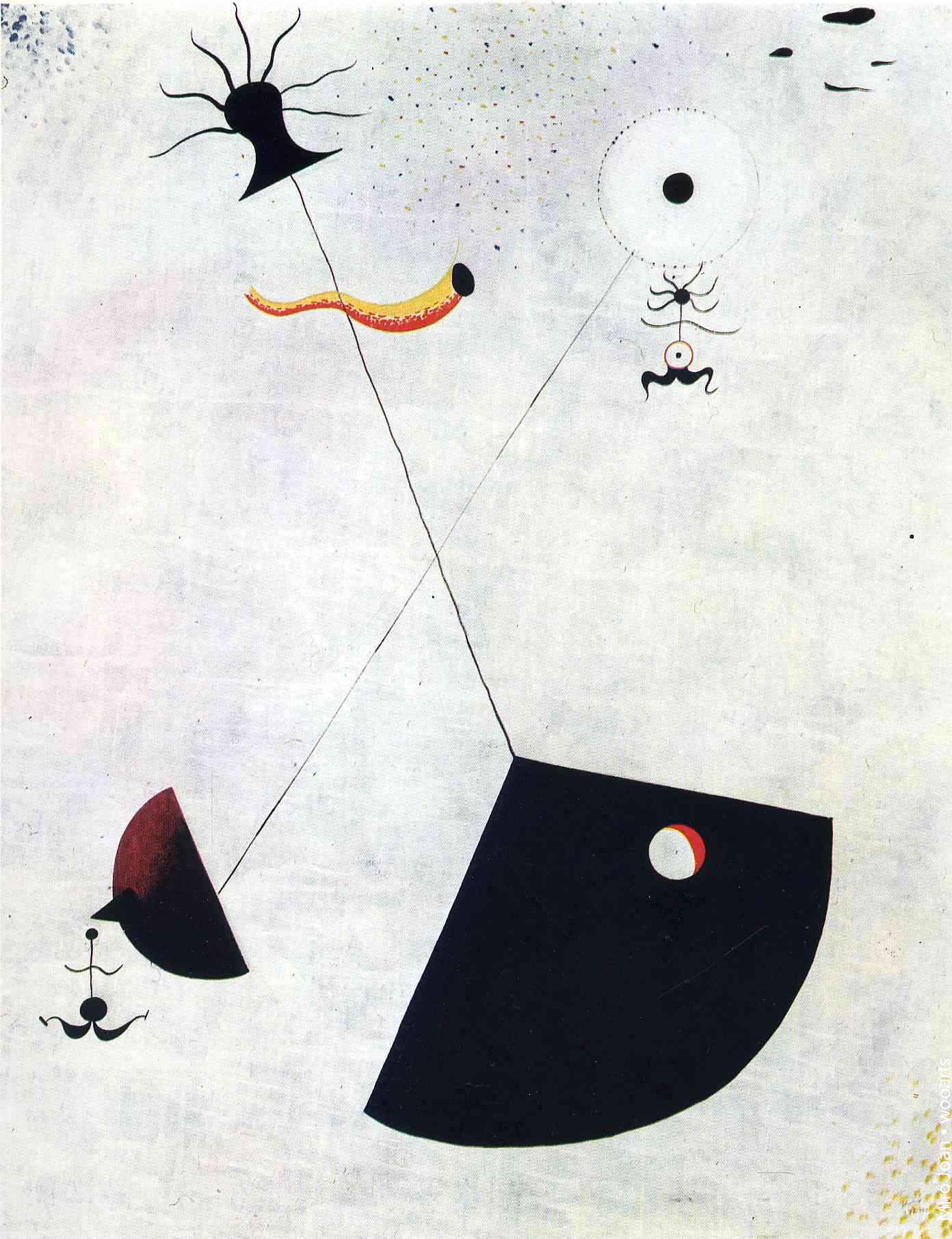

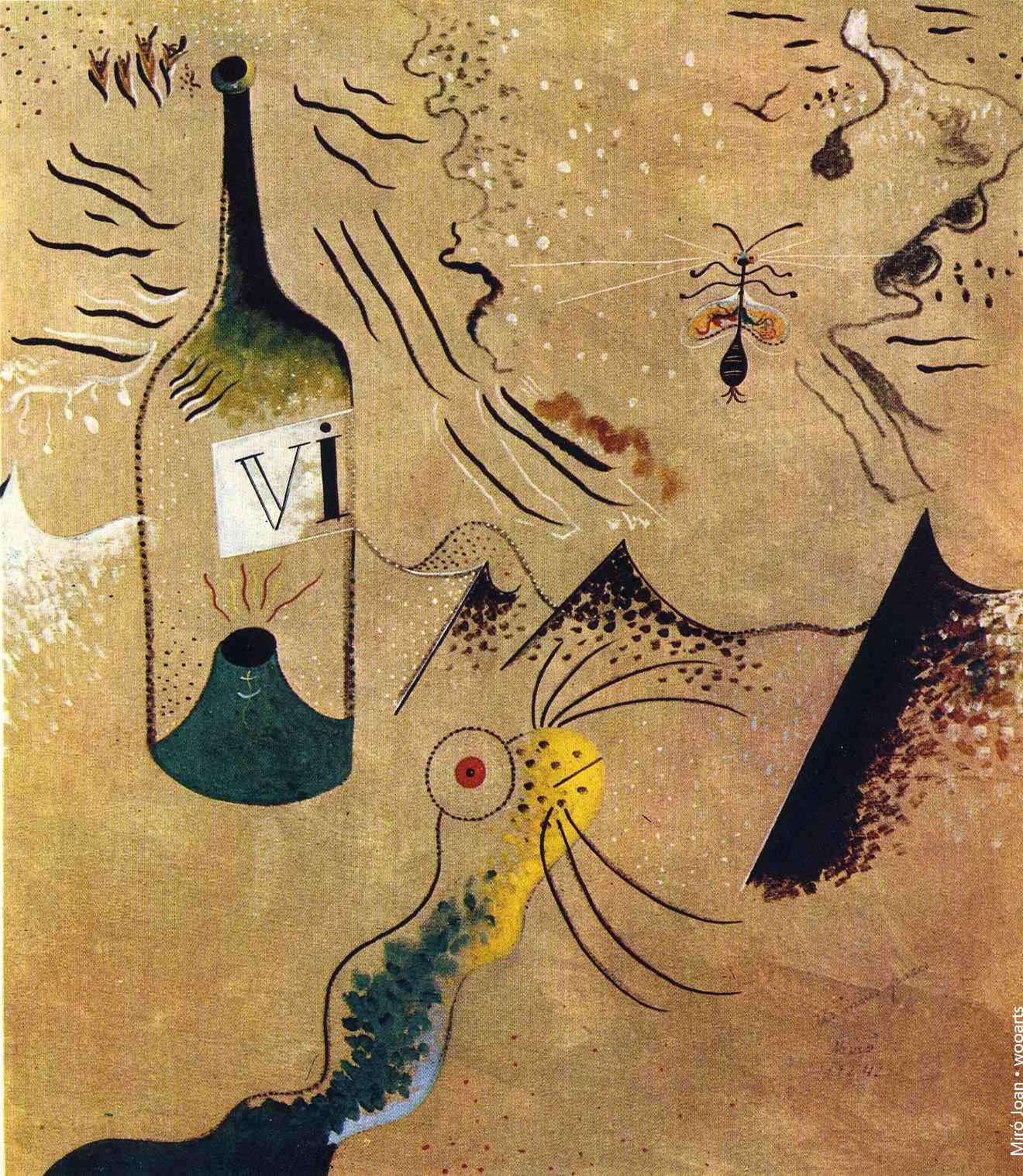

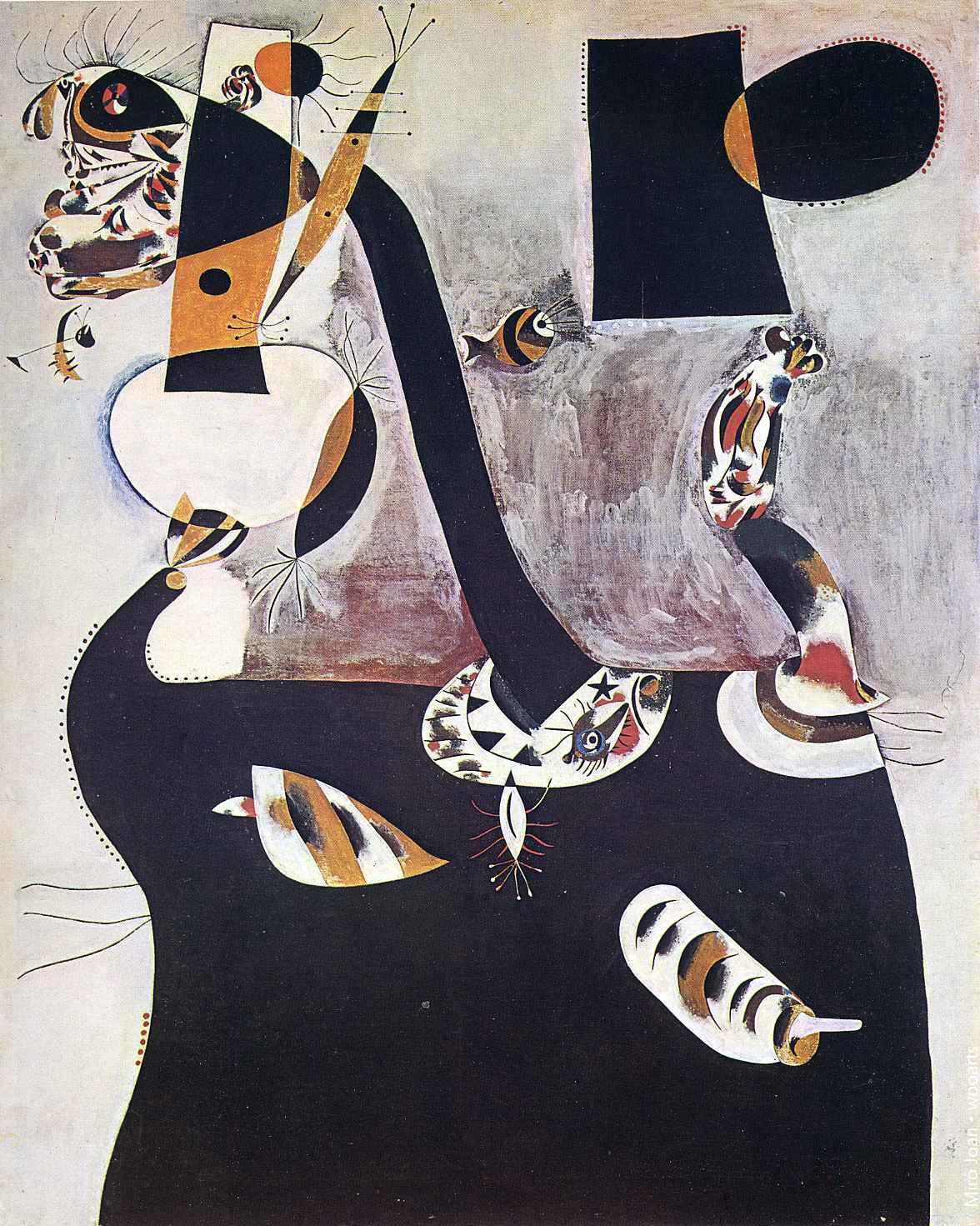

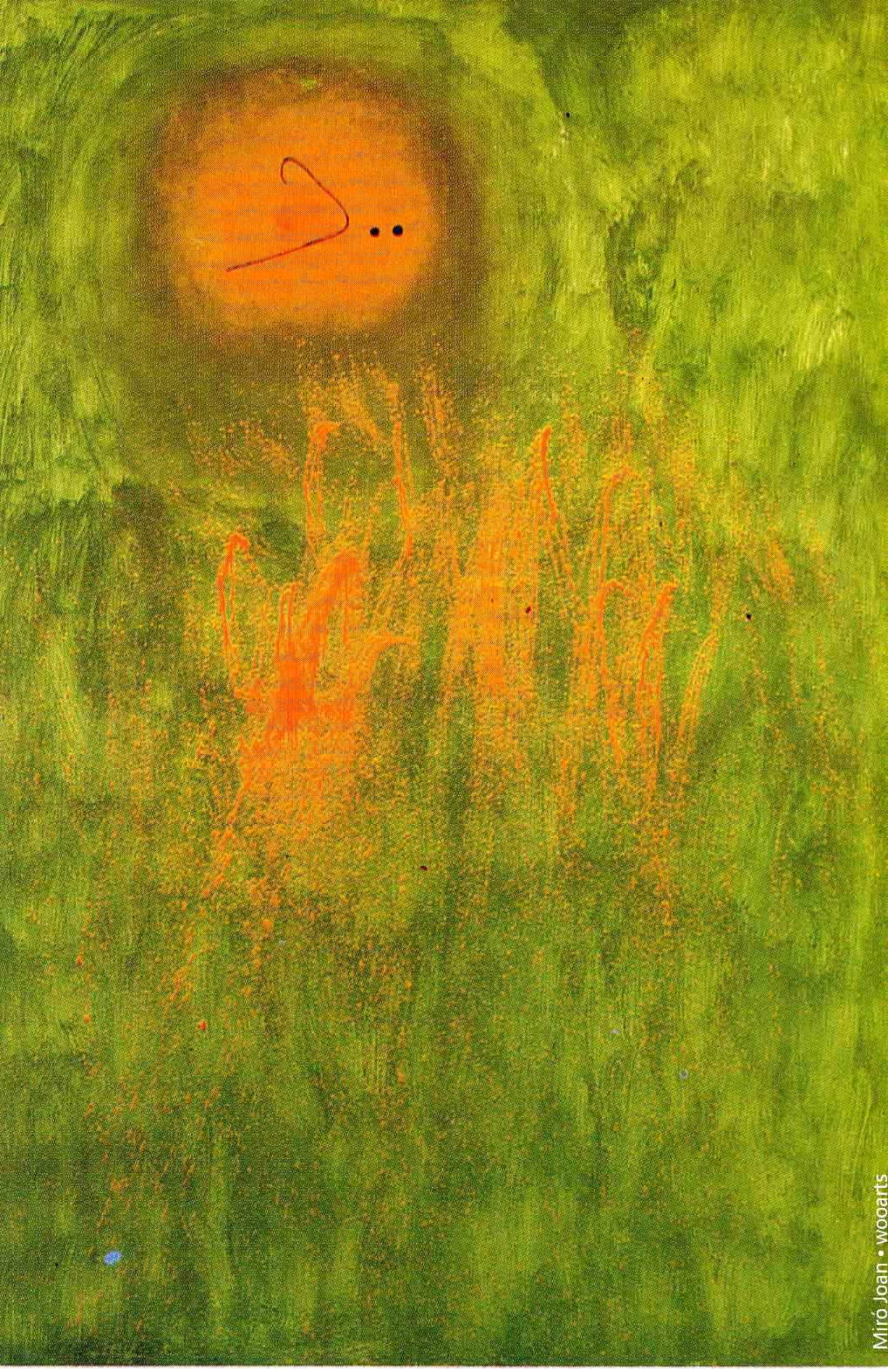

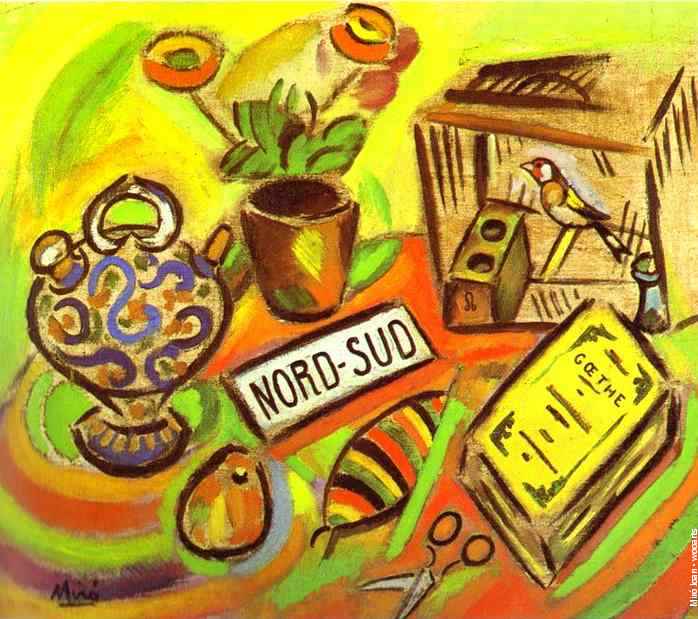

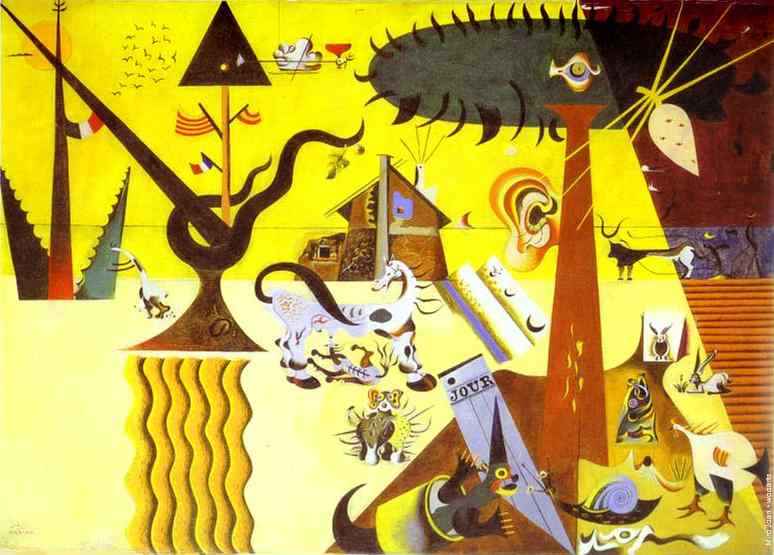

Joan Miró’s painting The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) brings together the real and the imaginary, abstraction and figuration, and image and text in a way that would characterize much of his work to come. In the canvas—a landscape filled with personal symbols and evocations of life on his family’s farm in Montroig, Spain, such as a tree trunk sprouting a leaf and the eponymous hunter carrying a freshly killed rabbit—he rendered the everydayness of the farm with a poetic intensity. This impetus to reveal the marvelous in the quotidian attracted the attention of André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, who acquired The Hunter in 1925. Breton would later deem Miró’s arrival in Paris in the early 1920s “an important stage in the development of surrealist art.” 1 Indeed Miró’s studio in Paris soon became an “avant-garde laboratory”2 and gathering place for artists and writers, including André Masson (whose studio adjoined Miró’s), Antonin Artaud, and Robert Desnos.

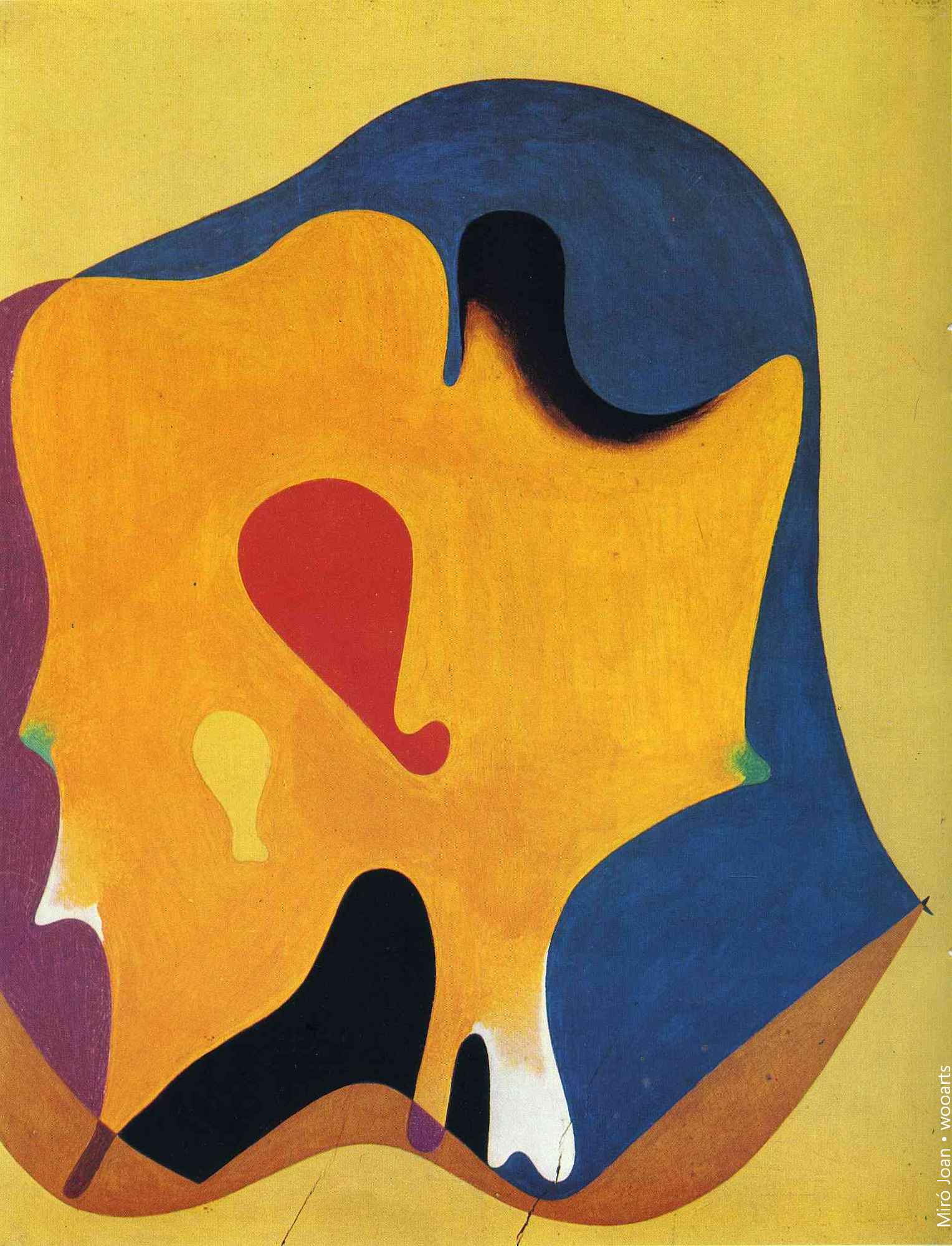

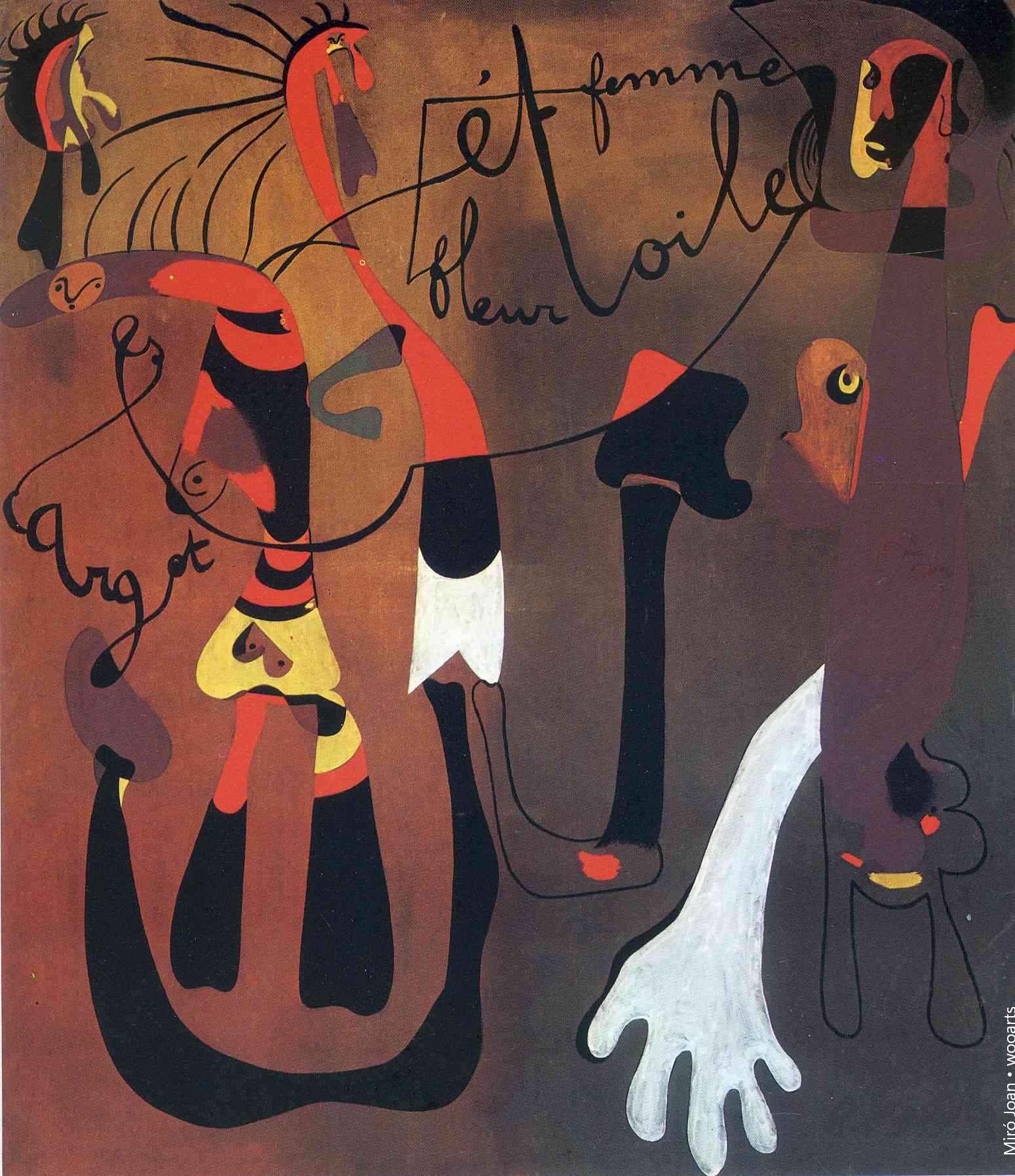

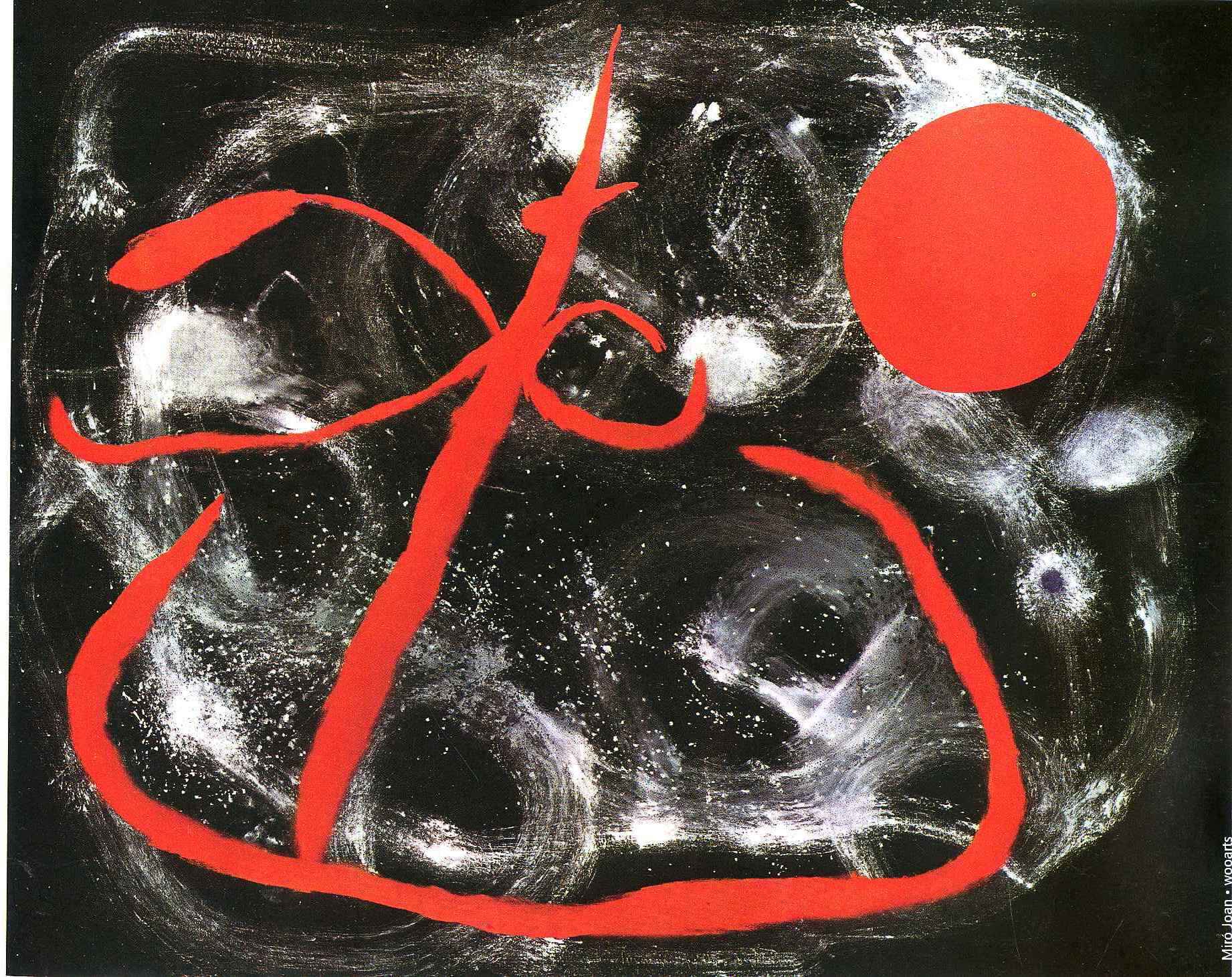

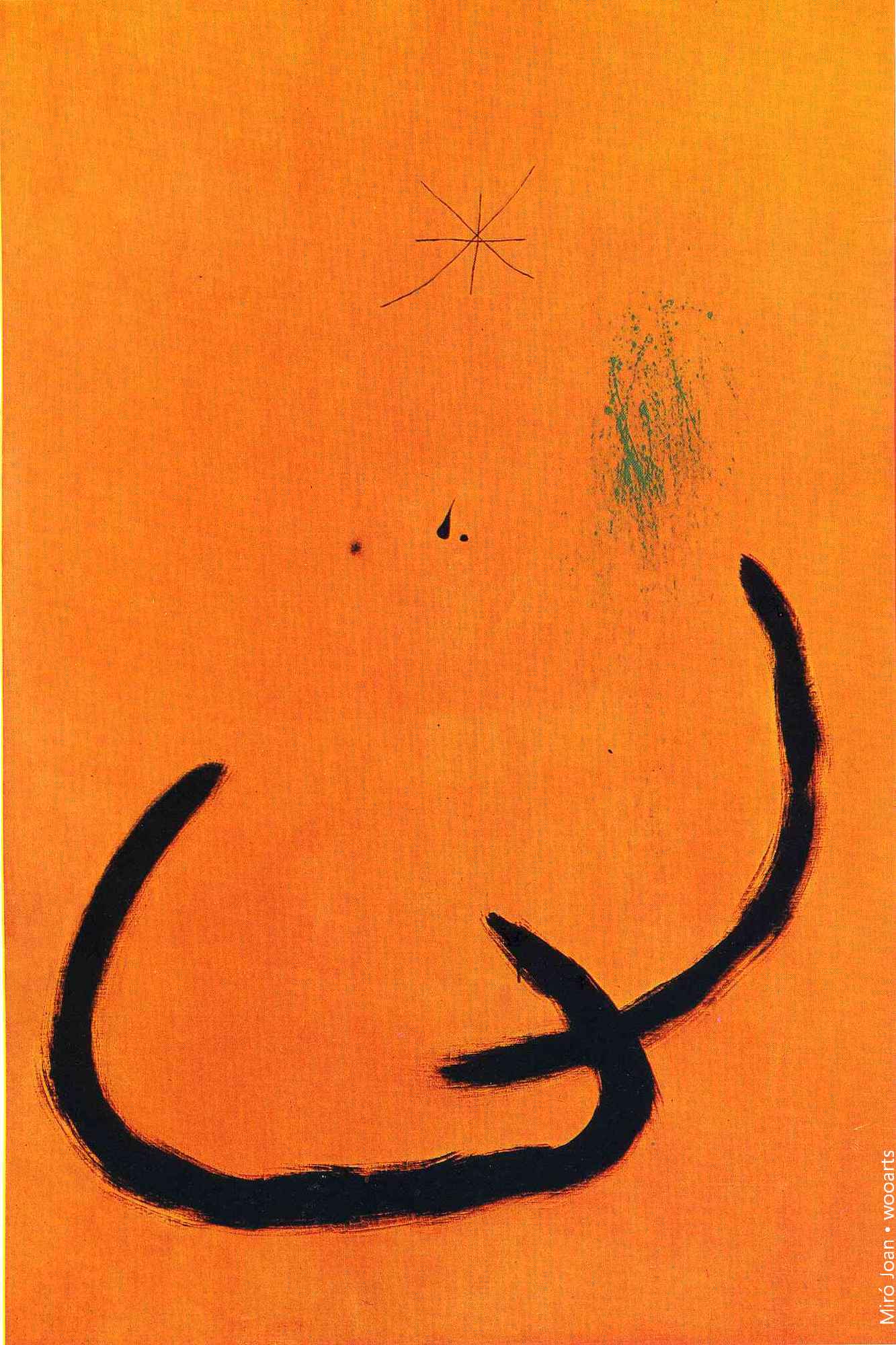

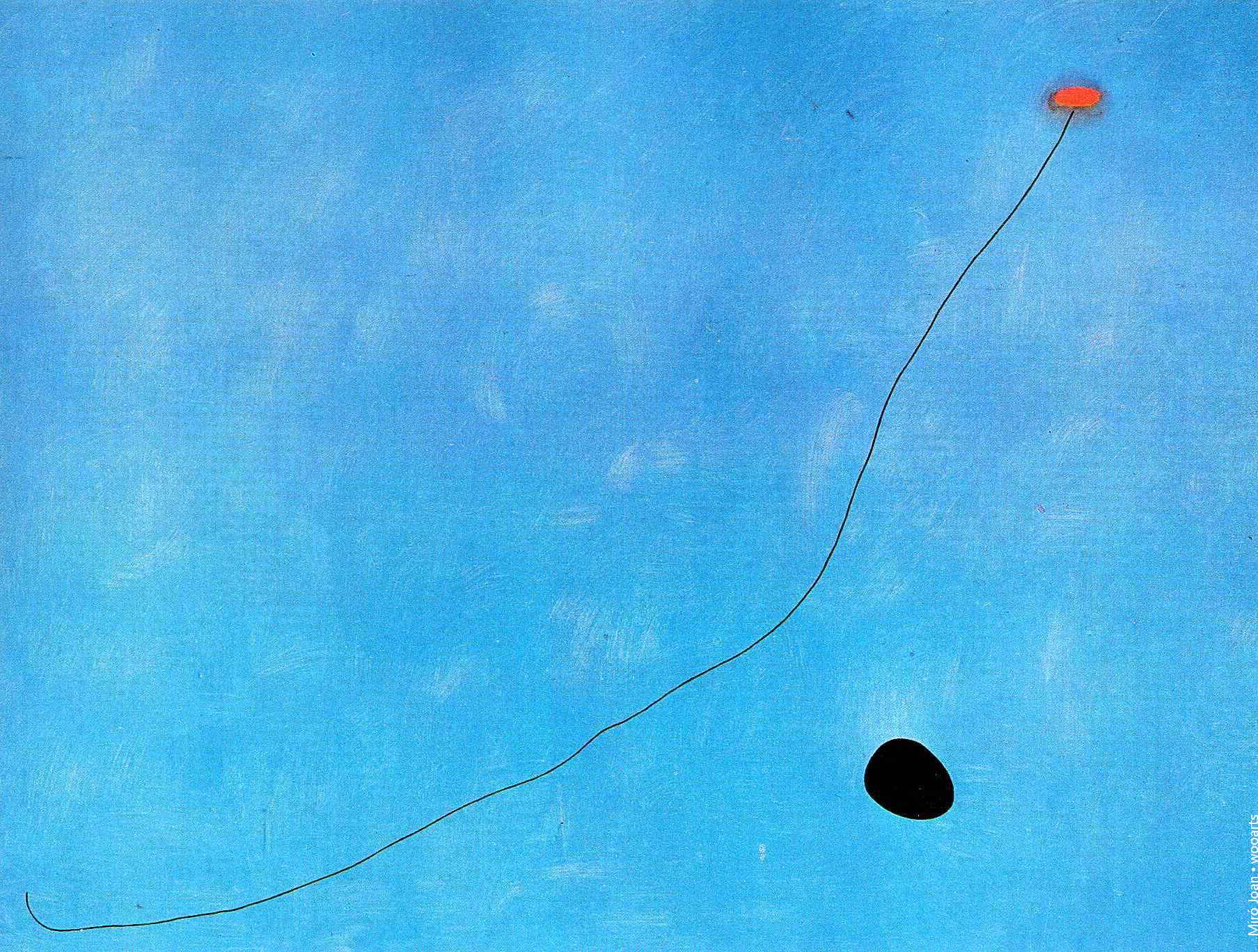

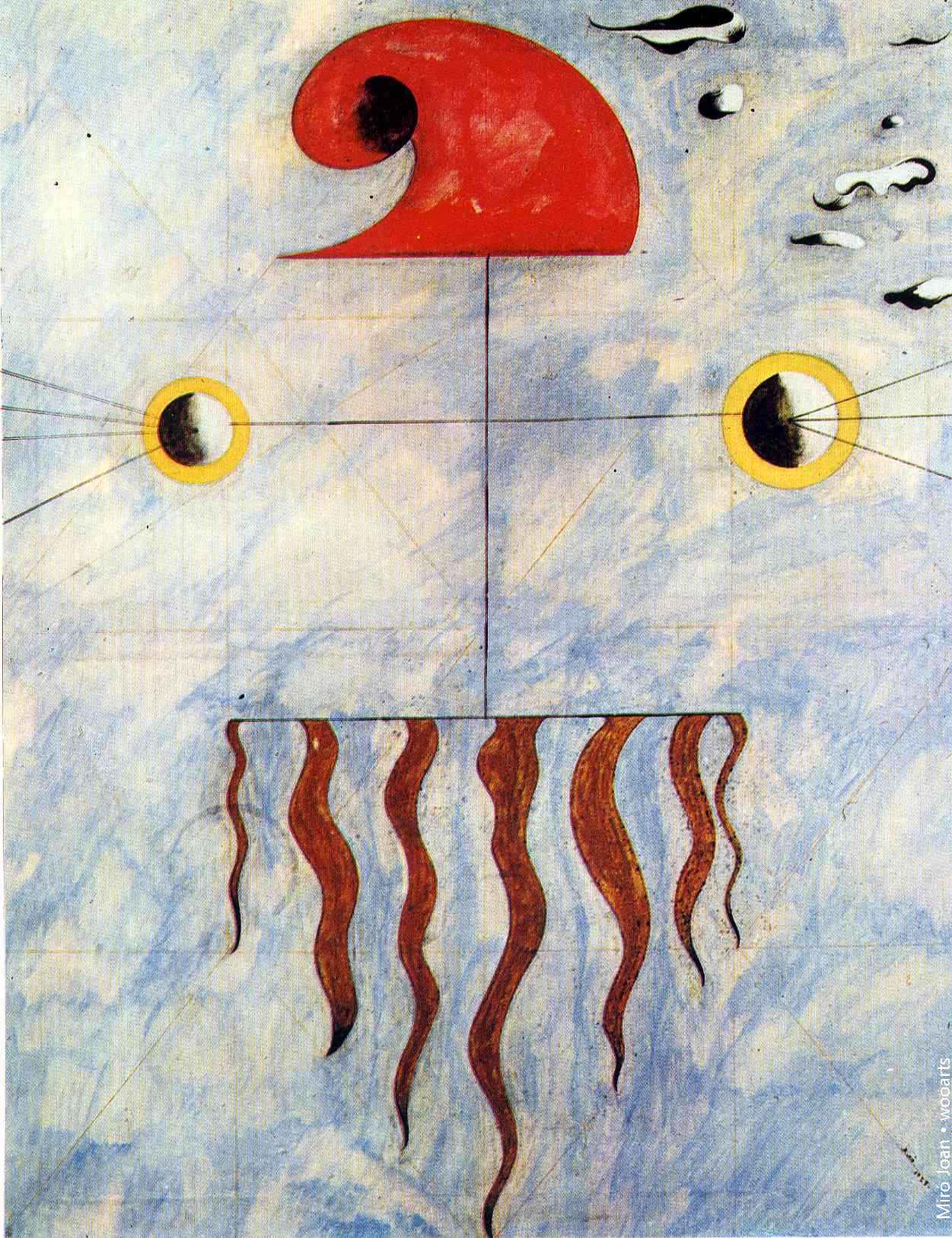

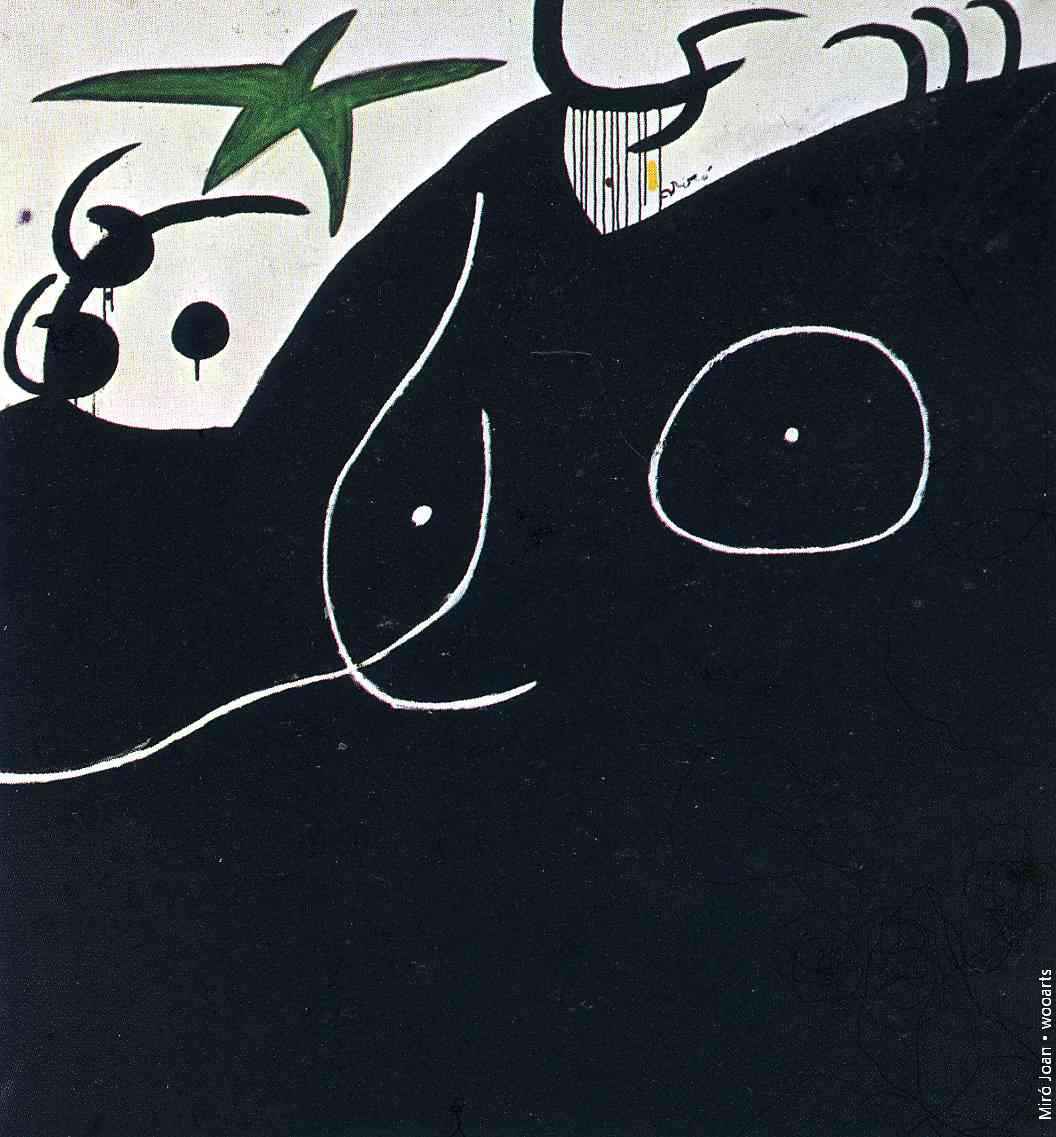

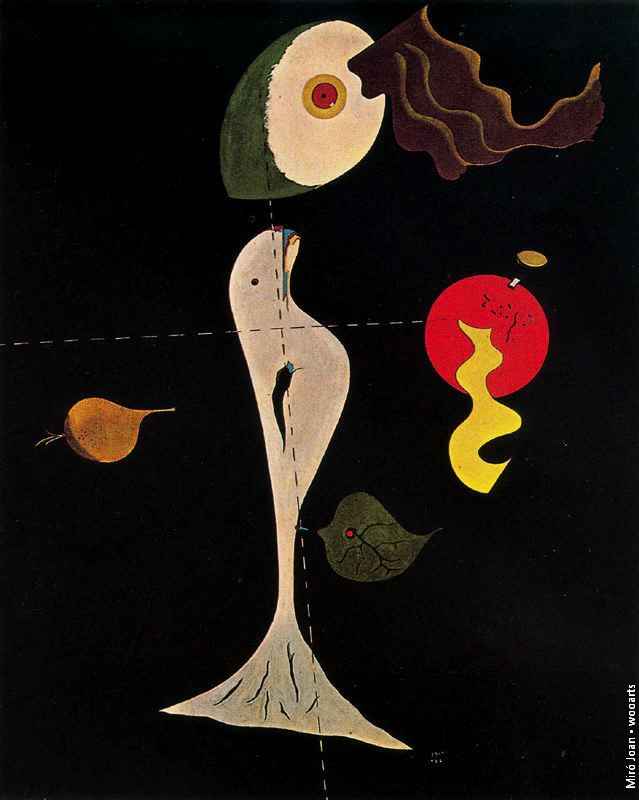

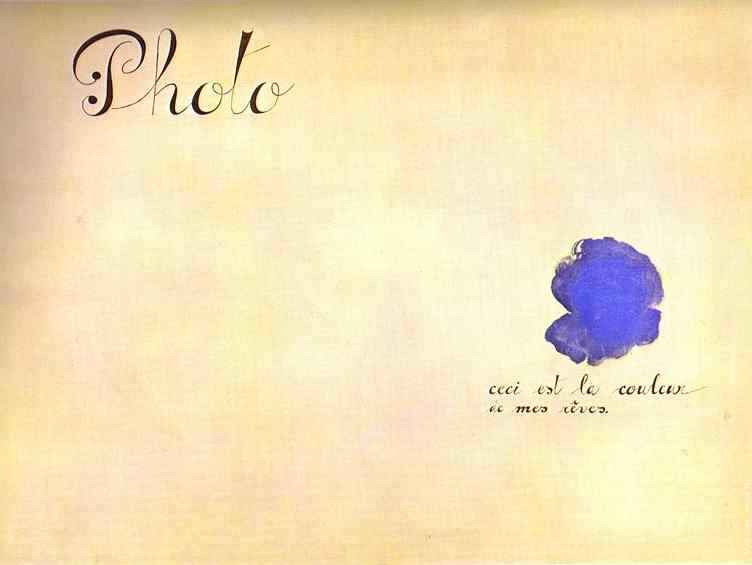

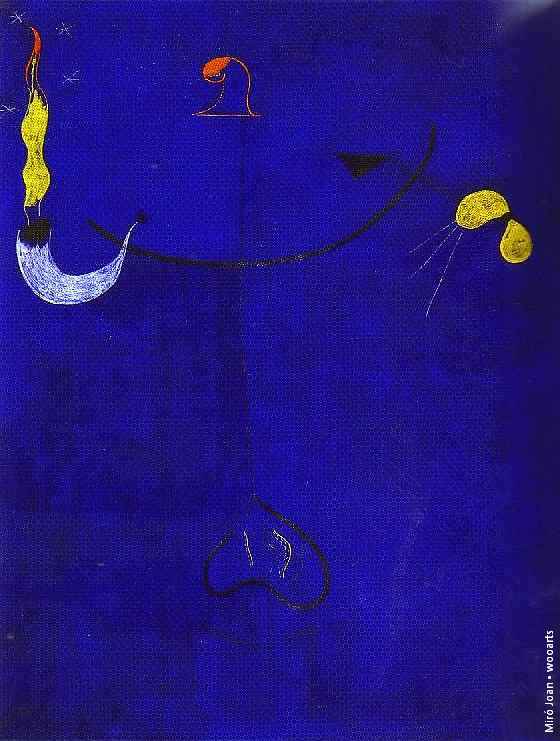

According to Breton, the Surrealists sought to liberate “the real functioning of the mind” through “a pure psychic automatism,” free of “any control exercised by reason.”3 Their approach to art making, as defined by Breton, inspired Miró. He later recounted, “Rather than setting out to paint something, I begin painting and as I paint the picture begins to assert itself….,The first stage is free, unconscious.” But, he continued, “The second stage is carefully calculated.”4 The Birth of the World reflects this blend of spontaneity and deliberation. Although its brushy, atmospheric background was freely applied, the individual motifs and their arrangement were sketched out in advance. In this and many of his following works, Miró attempted to give free rein to the unconscious, as the Surrealists did, at the same time as he sought to formulate a new pictorial language.

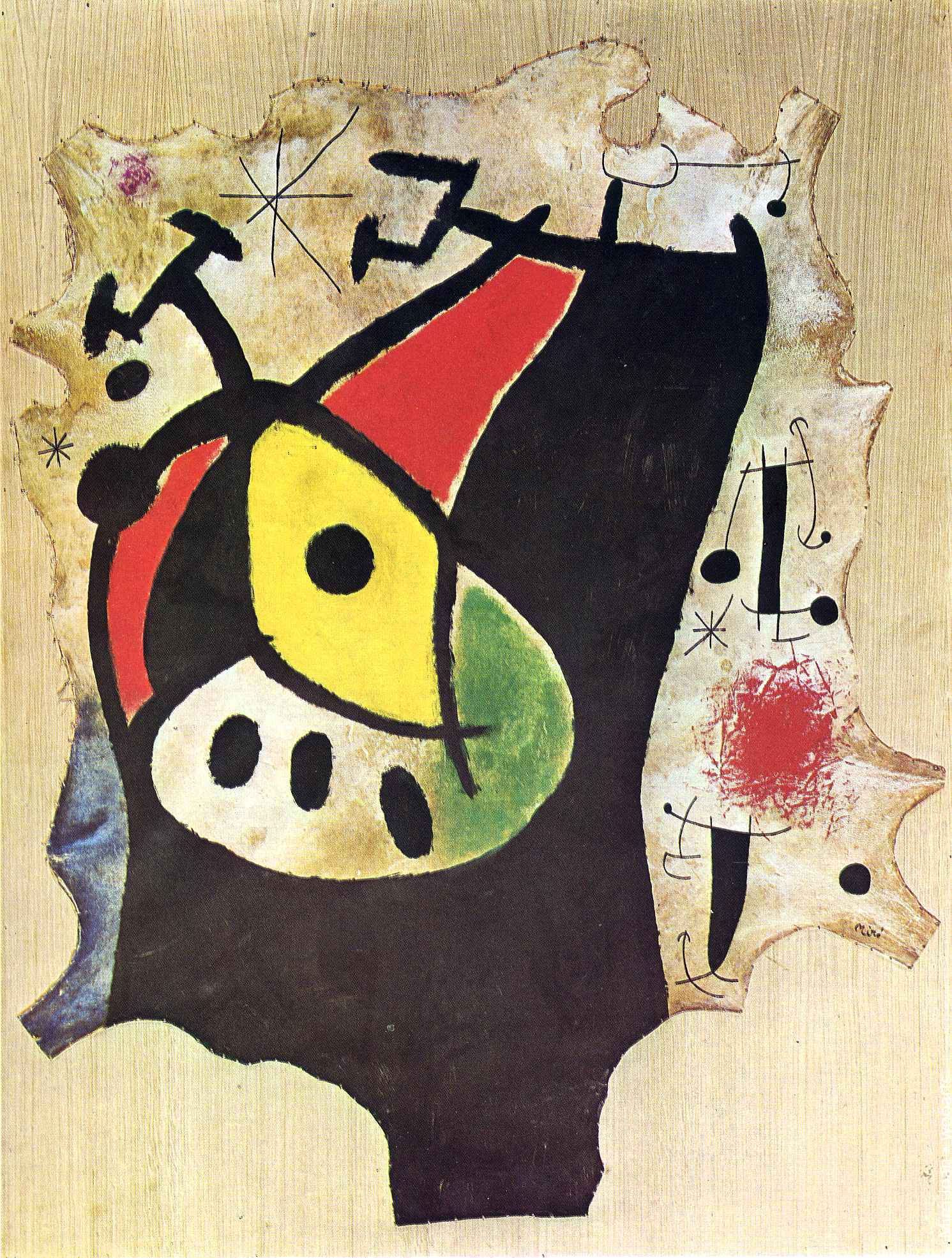

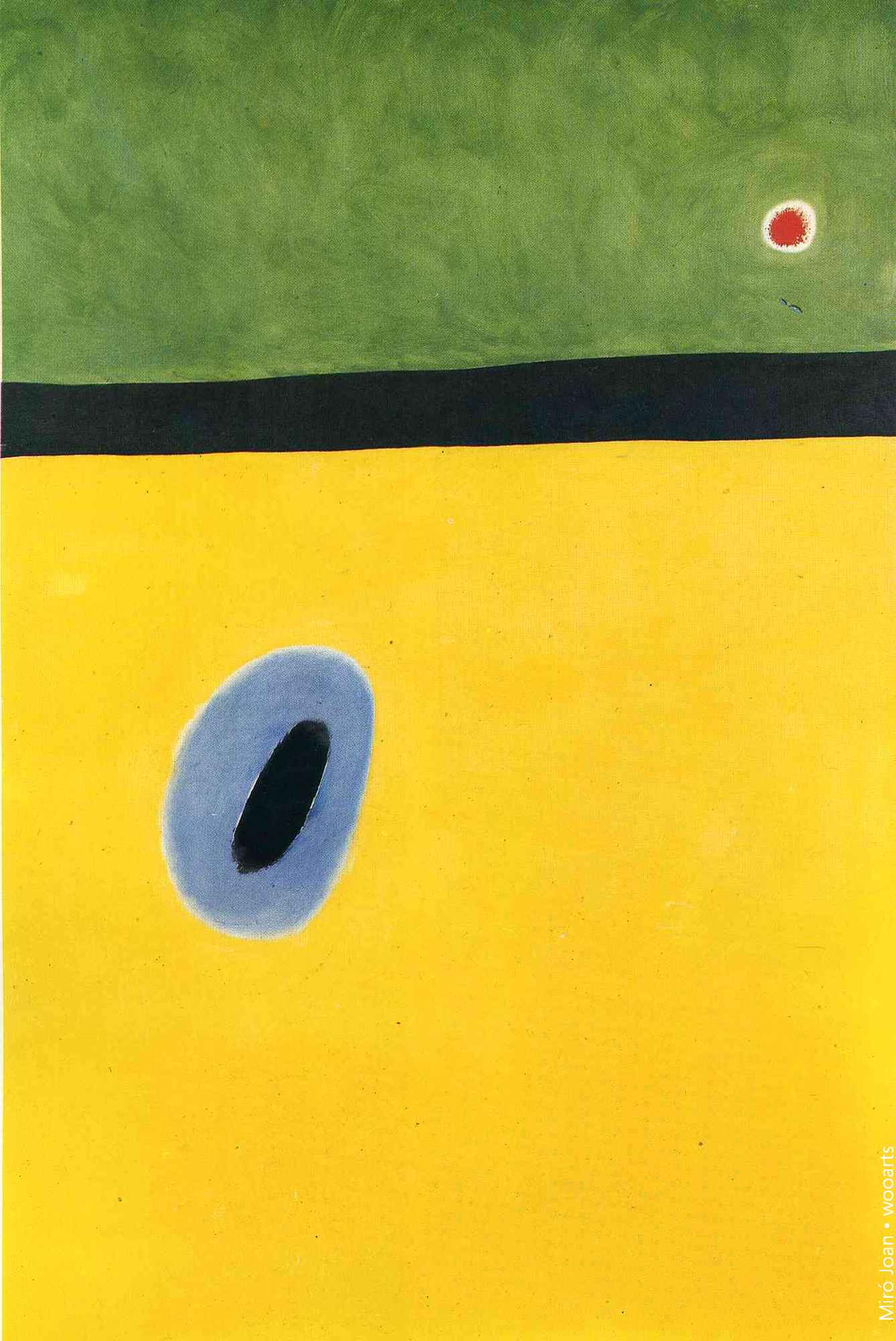

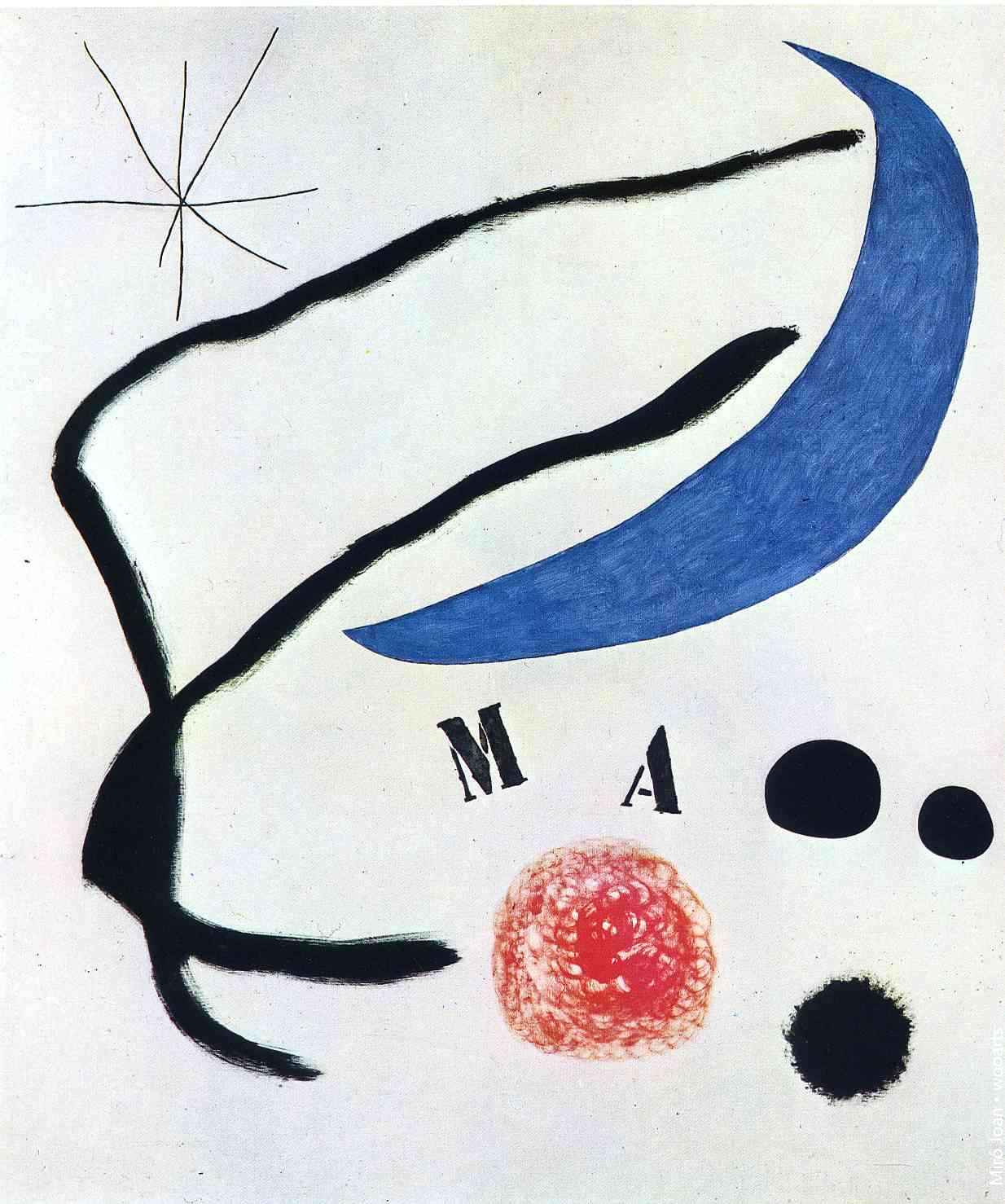

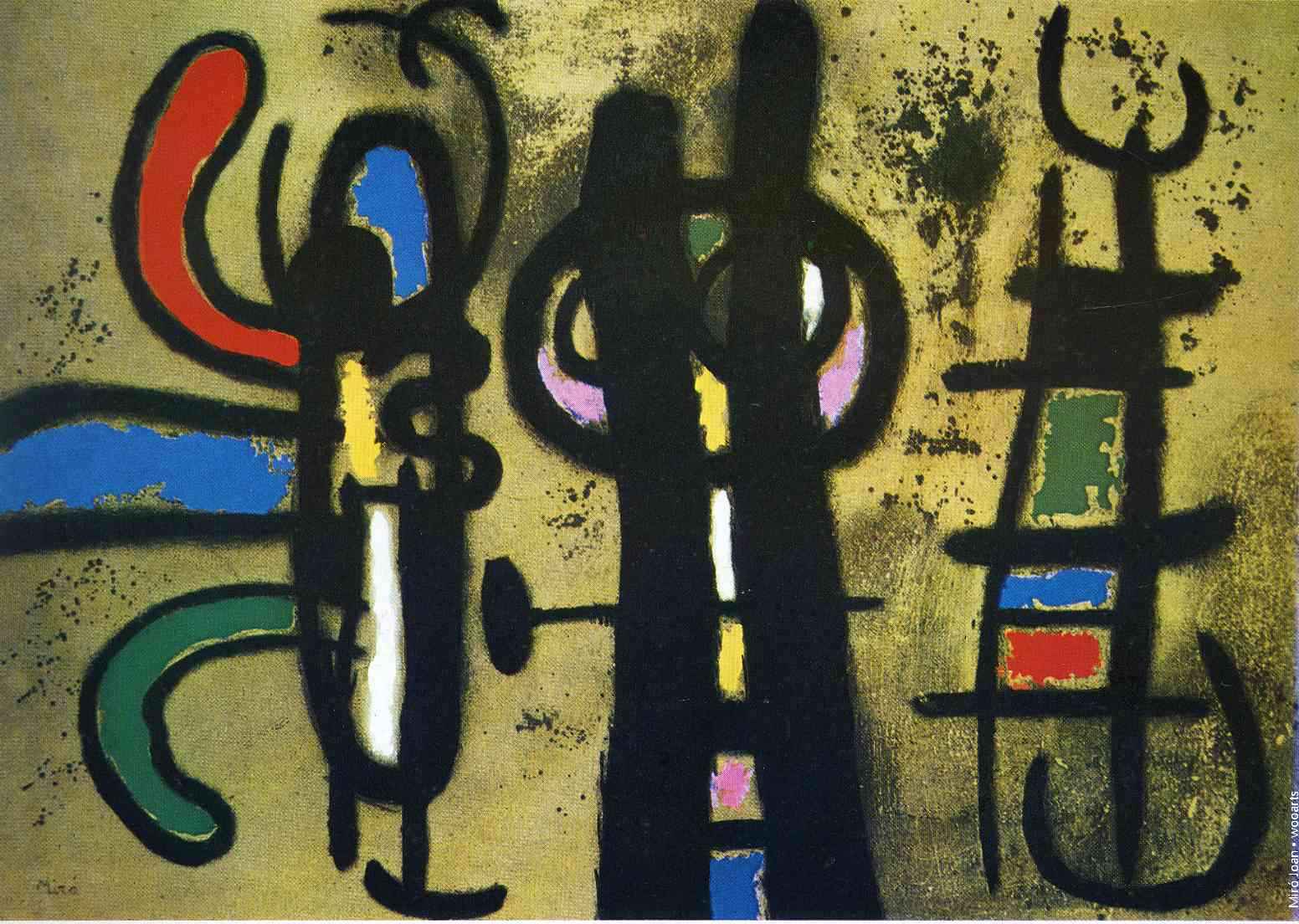

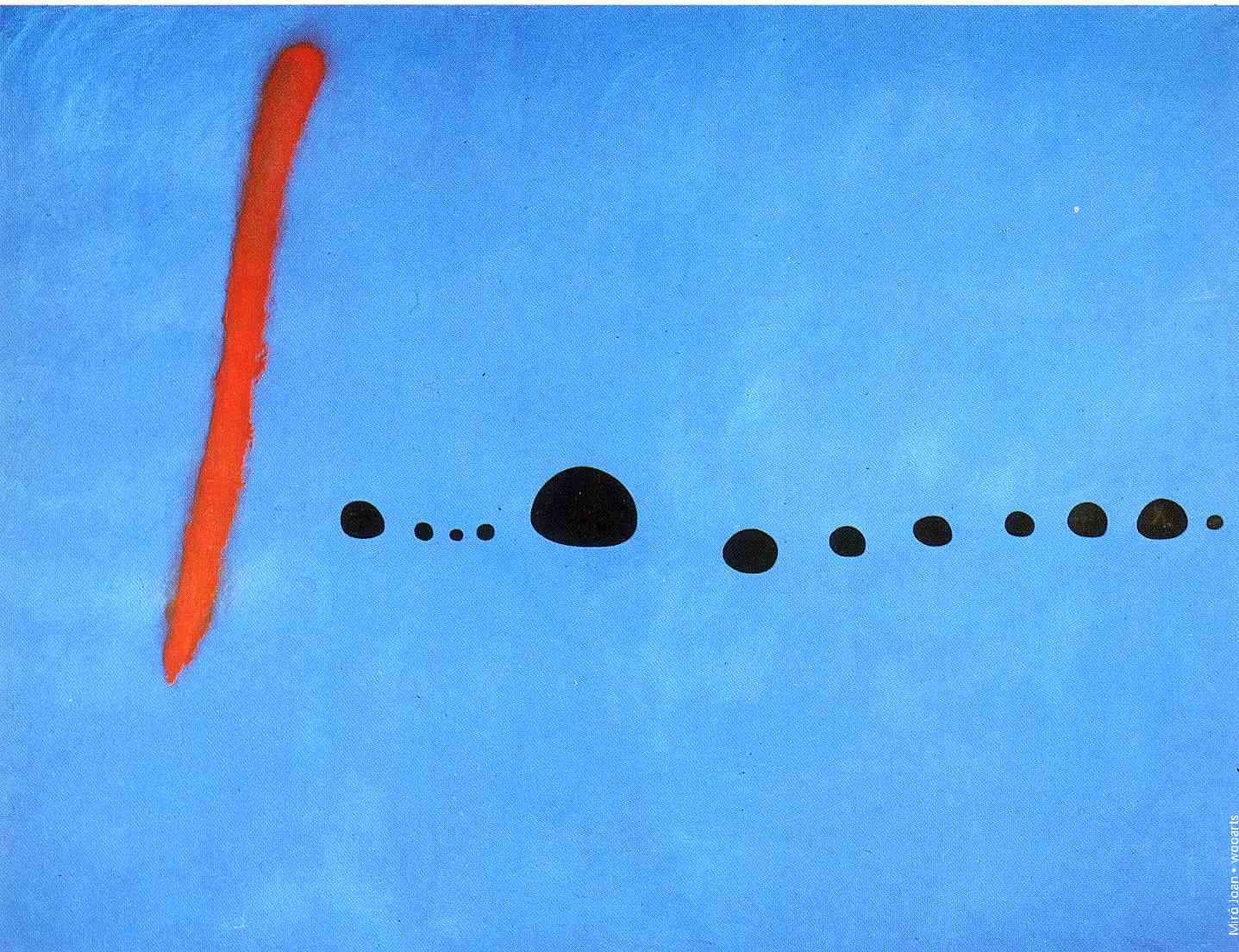

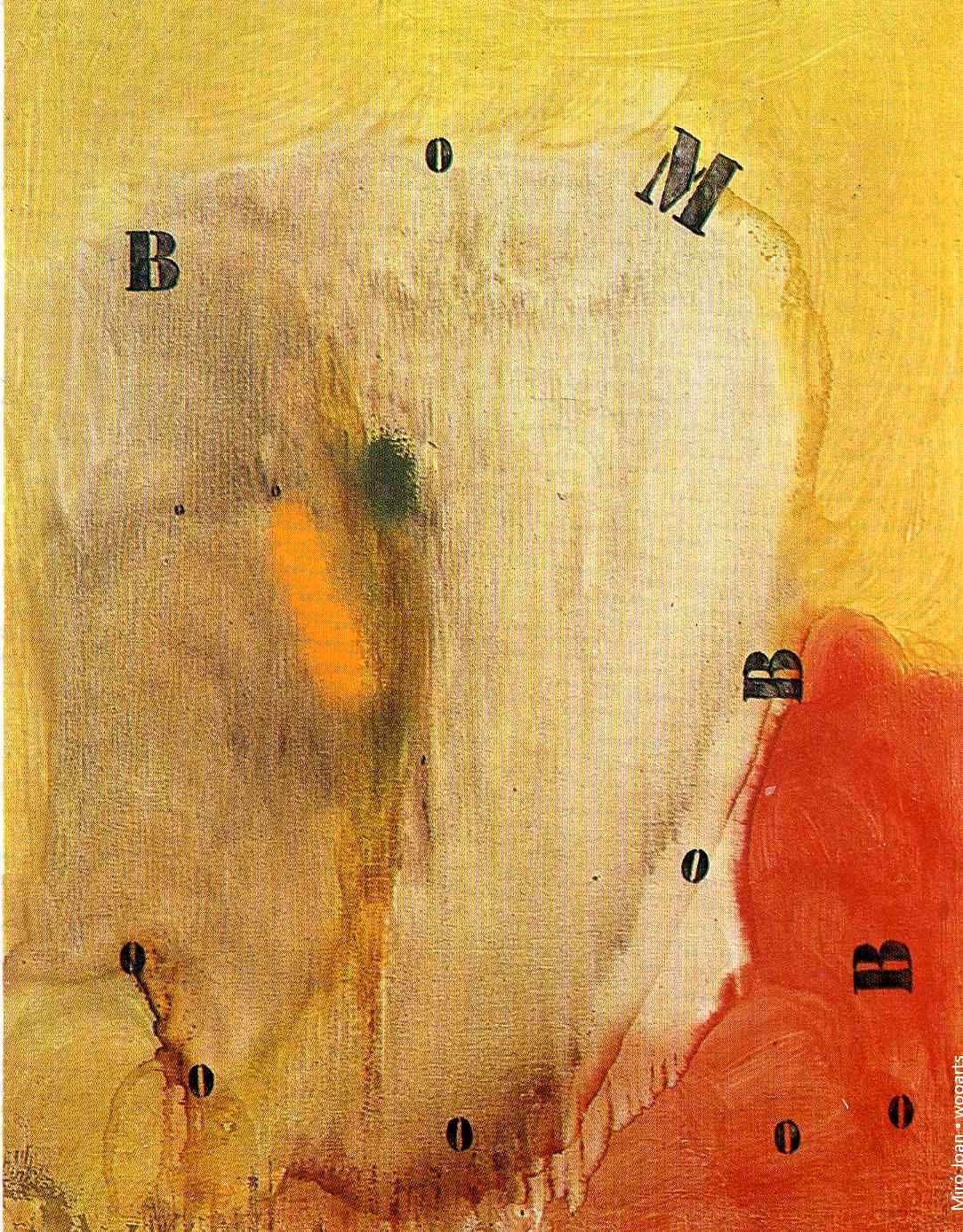

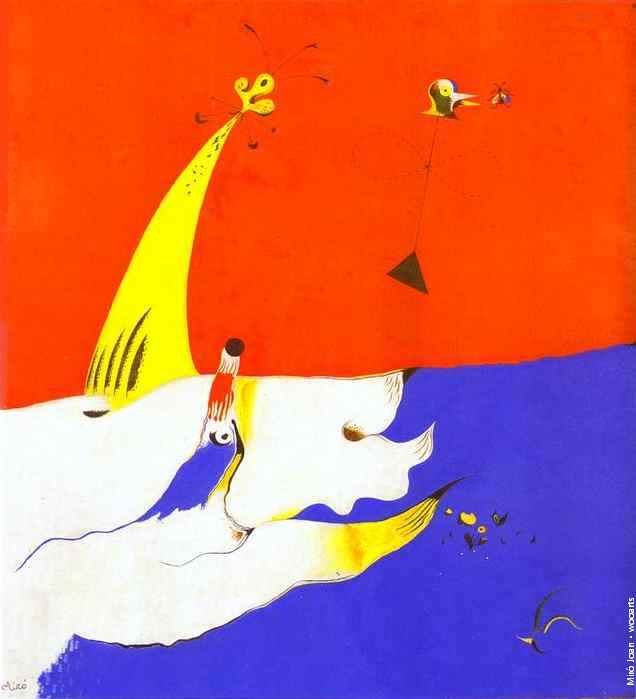

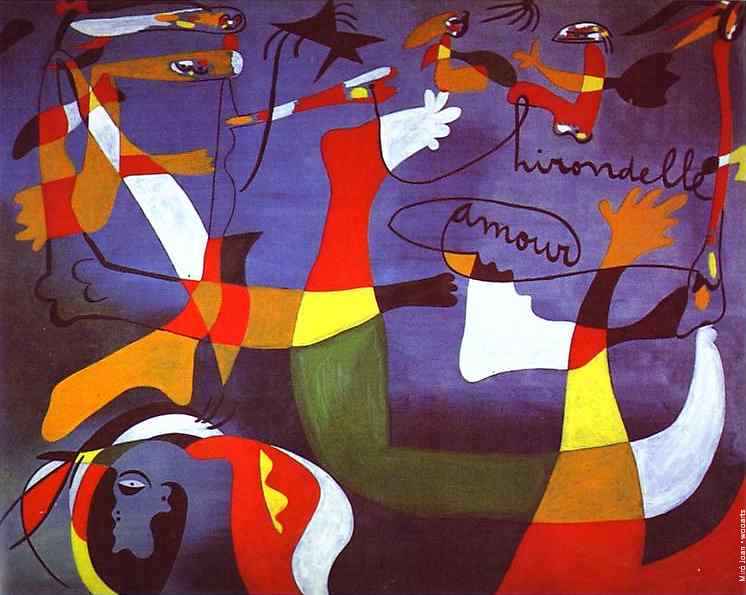

Beginning in the late 1920s, Miró embarked on a period of experimentation with mediums and techniques, attacking the limits of painting in order to reinvigorate it. He successively made works on unprimed canvases, white grounds, flocked paper, cardboard, Masonite, and copper; collages, paintings based on collage, and so-called “drawing collages”; and constructions and objects. These experiments also included engagements with art history and with language. In Dutch Interior (I), part of a series based on 17th-century Dutch genre paintings, Miró reimagined illusionistic space, compressing and flattening the scene of the original painting into planes of non-naturalistic, unmodulated color. Later, the aerial, calligraphic “Hirondelle Amour” exemplified his peinture-poésie, or painting-poetry, as biomorphic forms and words seem to float in suspension above a blue expanse.

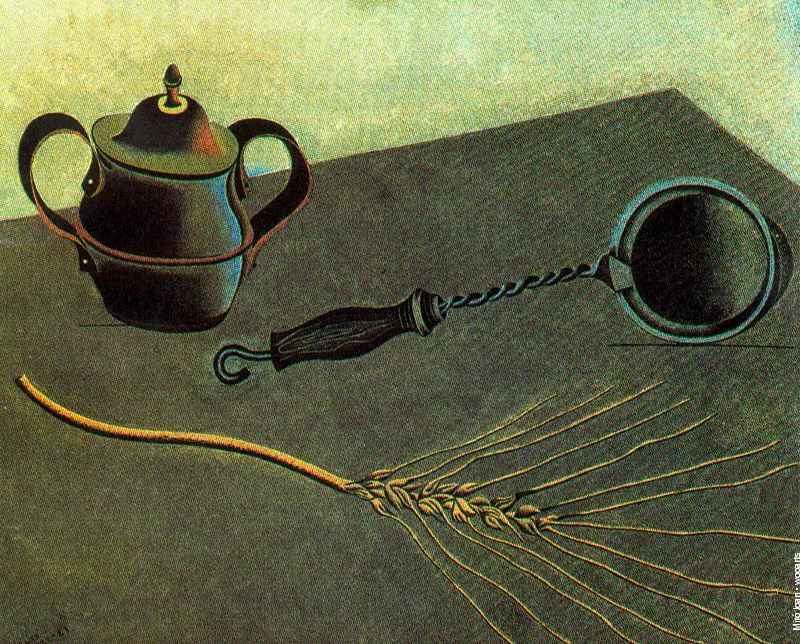

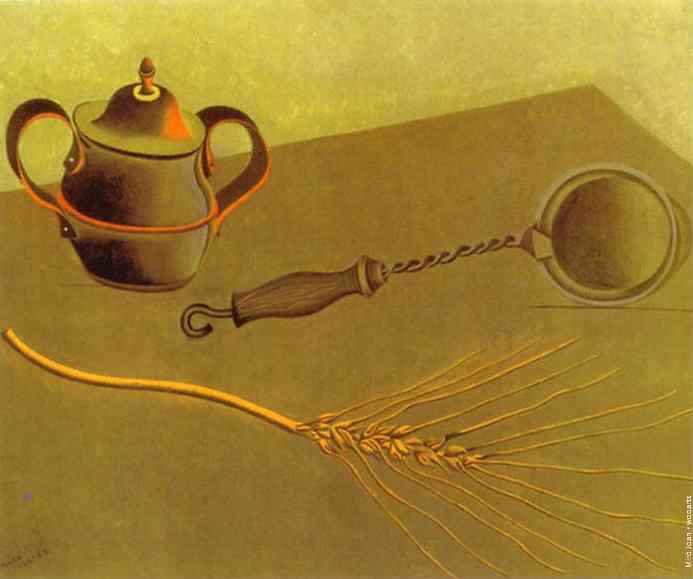

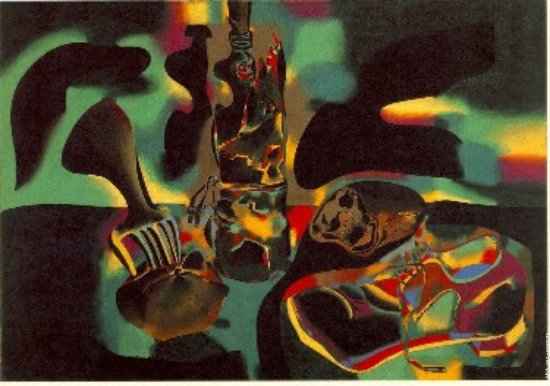

Still Life with Old Shoe brought an end to an intense, decade-long period of experimentation, as Miró announced his intention to do “something absolutely different.”5 The canvas, which he painted in Paris as the Spanish Civil War raged in his home country, marked his temporary return to working from life. It straddles the line between still life and landscape, even as the saturated, acidic colors and disproportionately scaled objects undermine its title’s—and Miró’s—proclaimed adherence to reality.

By 1939, World War II had come to the European continent. In this climate of danger and human catastrophe, Miró created the Constellations, a series of 23 gouaches on paper, including The Escape Ladder, which gave form to the transcendence and escape he longed for during those years. Interweaving his distinctive visual vocabulary with cosmic and earthly themes, these intimately sized works were easily transportable. In flight from the German invasion, he carried the earliest gouaches in the series, begun in France, back with him to the relative safety of Spain. Breton would later reflect that “Miró, at this hour of extreme anguish unfurl[ed] the full range of his voice,” sounding the same “note of wild defiance of the hunter expressed by the grouse’s love song.”6 After the war, Miró gained international recognition as he continued to experiment freely with different mediums, including ceramics, printmaking, book illustration, and sculpture.

via Moma.org