Ernst Josephson - David and Saul - National Museum

Background

He was born to a middle-class family of merchants of Jewish ancestry. His uncle, Ludvig Josephson (1832-1899) was a dramatist and his uncle Jacob Axel Josephson (1818-1880) was a composer. When he was ten, his father Ferdinand Semy Ferdinand Josephson (1814-1861) left home and he was raised by his mother, Gustafva Jacobsson (1819-1881) and three older sisters.

Career

At the age of sixteen, he decided to become an artist and, with his family’s support, enrolled at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. His primary instructors there were Johan Christoffer Boklund and August Malmström. He was there until 1876, when he received a Royal Medal for painting.

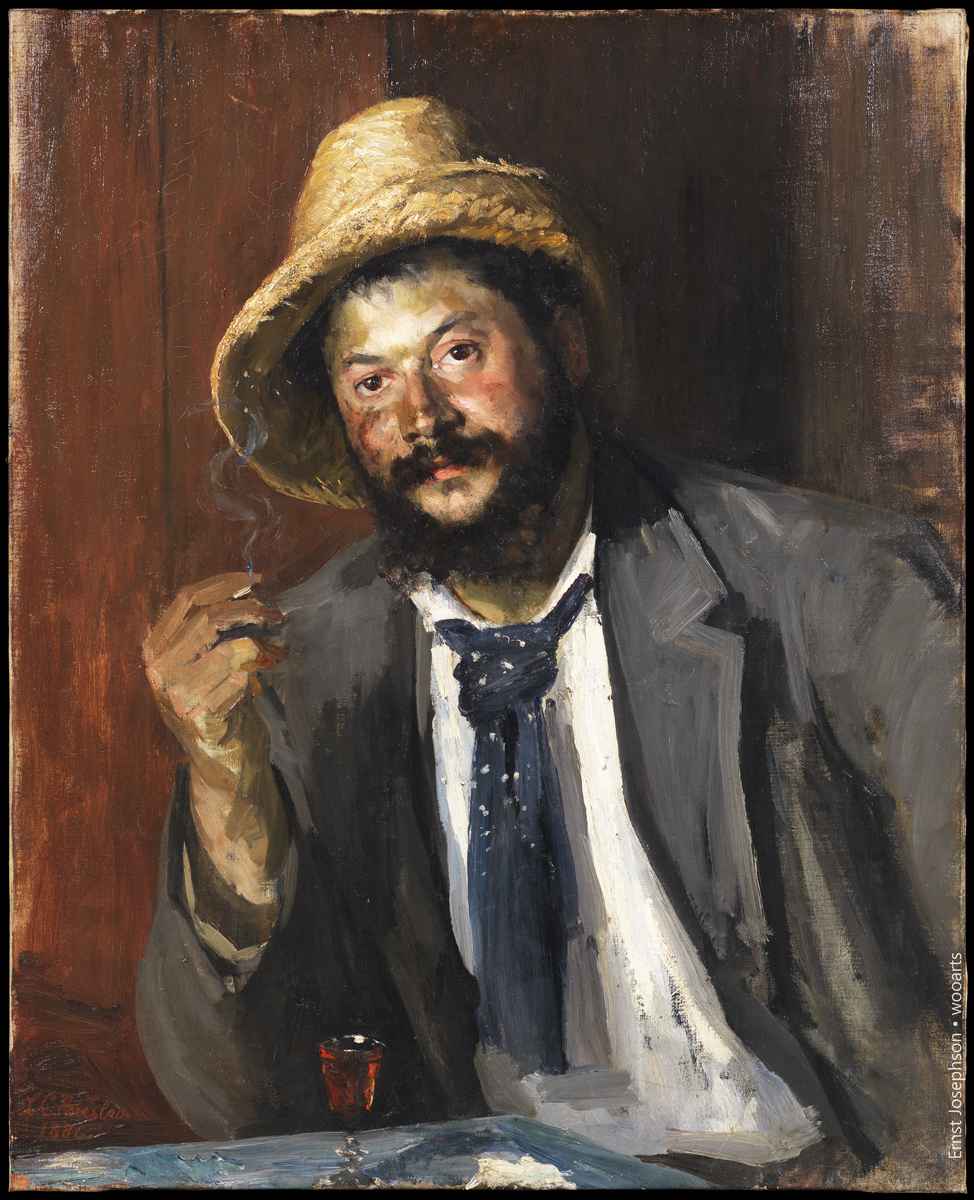

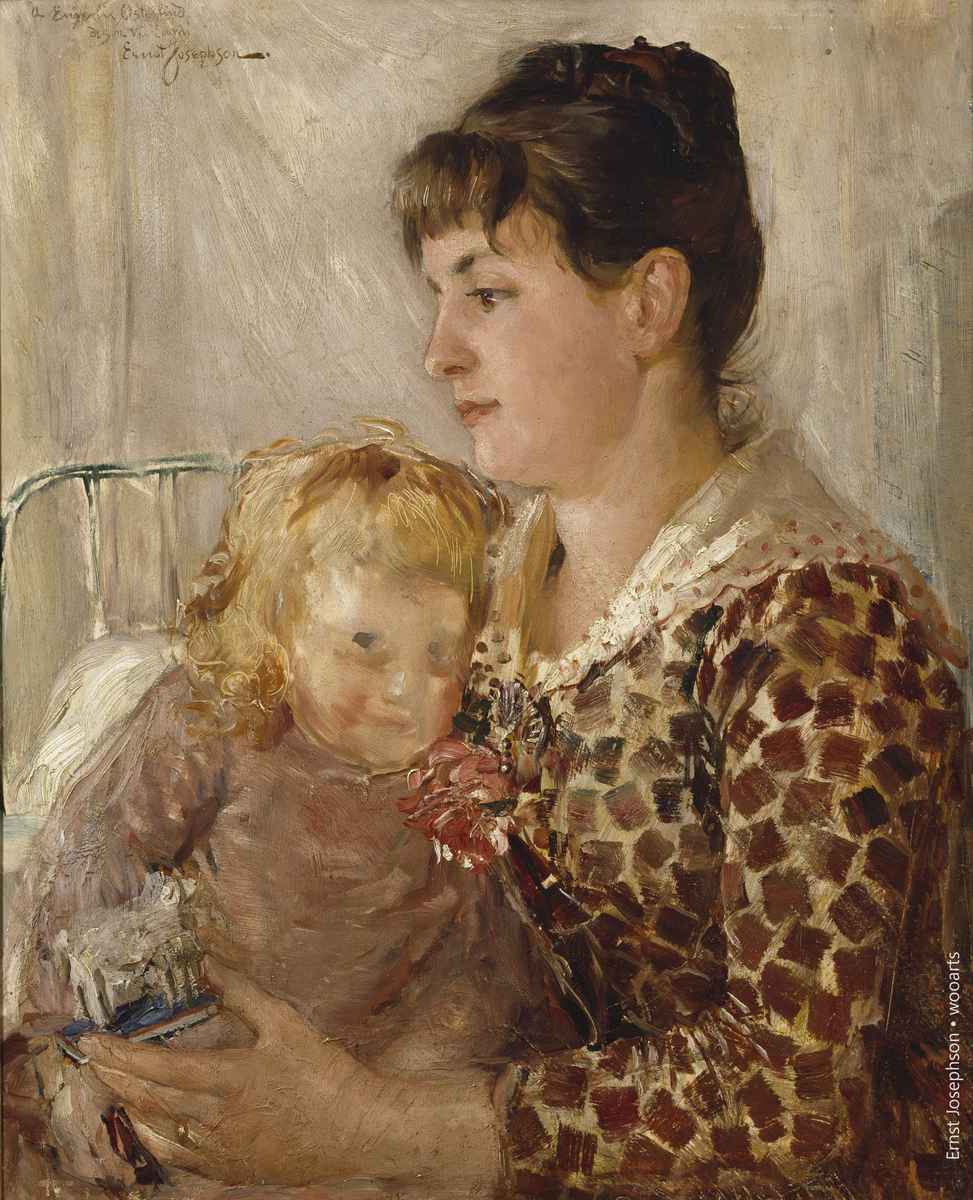

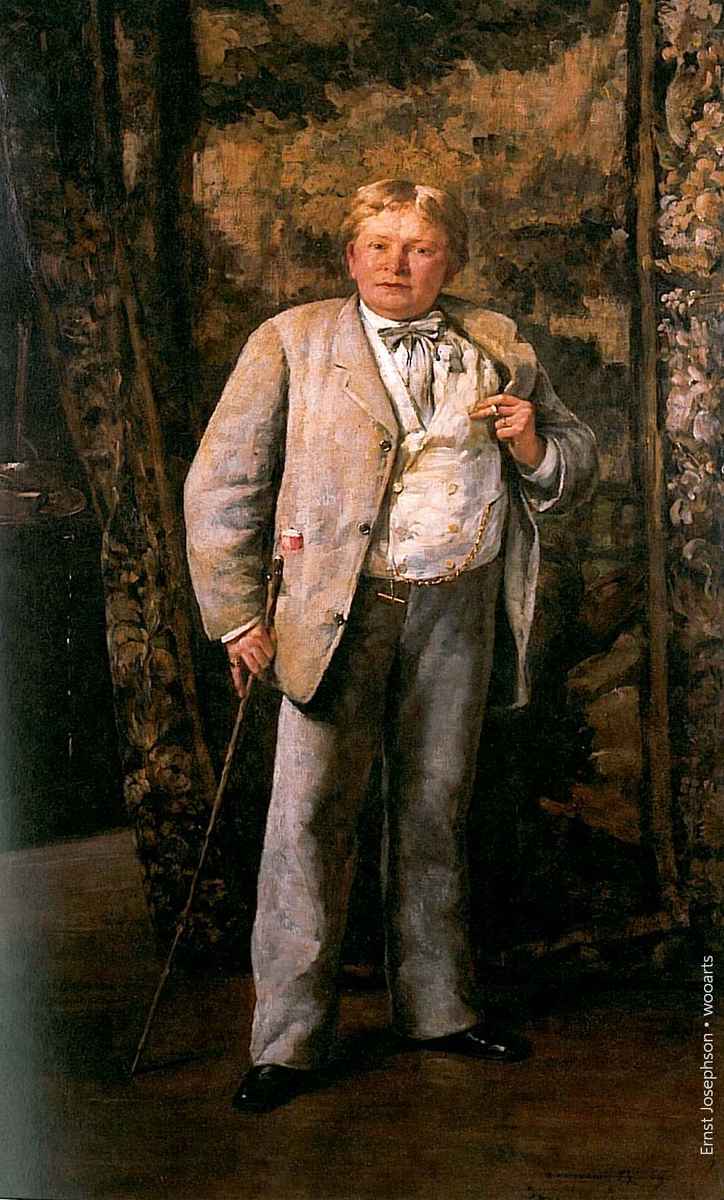

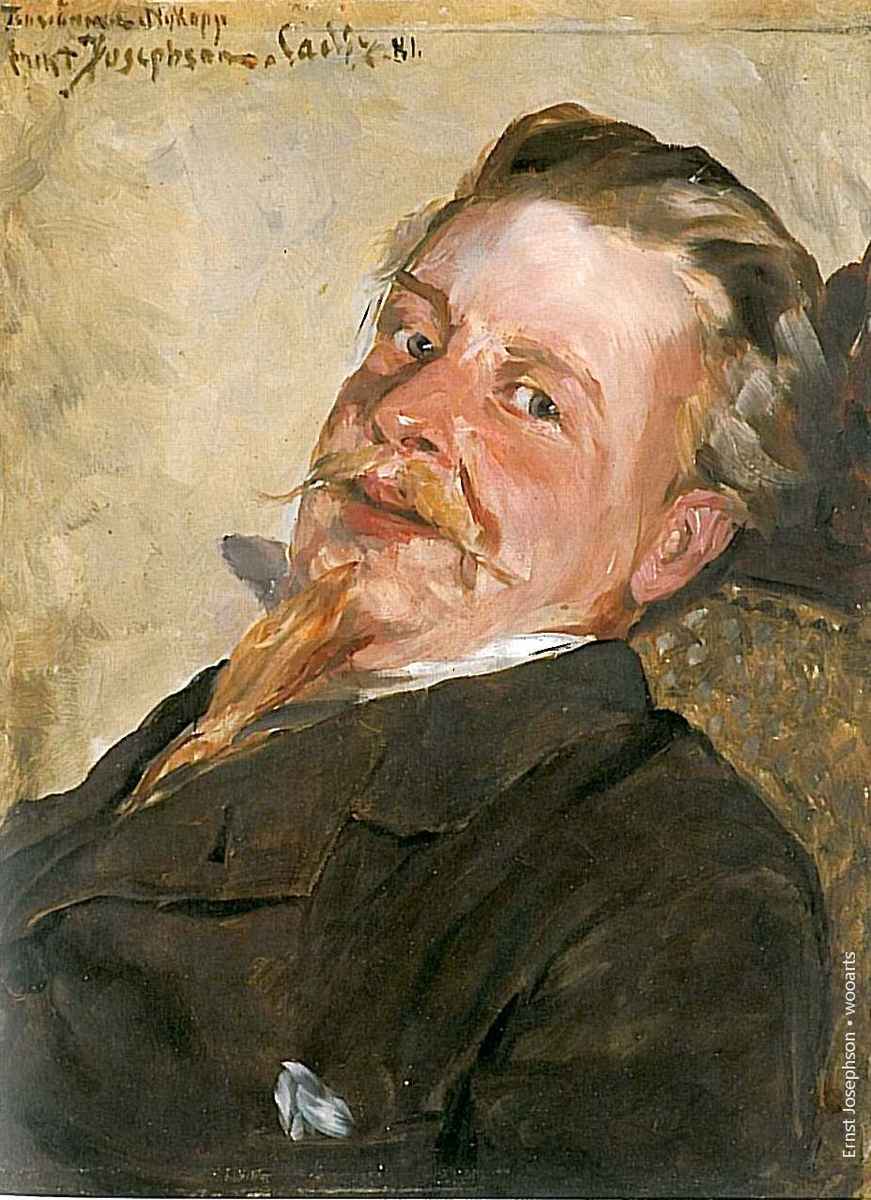

After leaving the Academy, he and his friend and fellow artist Severin Nilsson (1846-1918) visited Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, where they copied the Old Masters. His breakthrough came in Paris, where he was able to study with Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Arts. He soon began concentrating on portraits, including many of his friends and fellow Swedes in France. For a time, he shared a studio with Hugo Birger (1854–1887). His personal style developed further during a trip to Seville with his friend, Anders Zorn, from 1881 to 1882.

His private life did not go well, however. By his late twenties, he was afflicted with syphilis. His romantic life suffered as a consequence, as he was forced to break off a promising relationship with a young model named Ketty Rindskopf.

In the 1880s, a painting that is now considered one of his masterpieces, Strömkarlen (1882-1884) was rejected by the Nationalmuseum. It was eventually purchased by Prince Eugen (1865-1947), himself a skilled amateur artist and art patron, who hung it at his home, Waldemarsudde, now a museum on Djurgården in Stockholm. In total Ernst Josephson is also represented at the museum with ten other oil paintings and a large number of drawings.

In 1881, his mother died. They had been very close and it affected him deeply. There was one bright spot; in 1883 he obtained the patronage of Pontus Furstenberg (1827-1902), a wealthy merchant and art collector. In 1885, he became a supporter of the “Opponenterna [sv]”, a group that was protesting the outmoded teaching methods at the Swedish Academy. But his interest in the group diminished when he failed to win election to their governing board.

By the summer of 1888, he was beginning to have delusions and hallucinations, brought on by the progression of his illness. He installed himself on the Île-de-Bréhat in Brittany, where he had spent the previous summer with painter and engraver Allan Österlind (1855-1938) and his family. There, he became involved in spiritism, possibly inspired by Österlind’s interest in occult phenomena. While in his visionary states, he wrote poems and created paintings that he signed with the names of dead artists. Some of his best known and most influential works were created during this period.

Shortly after, Österlind took him back to Sweden and he was admitted to Ulleråkers sjukhus [sv], a mental institution in Uppsala. He remained there for several months. The diagnosis was paranoia, but his condition would now most likely be called schizophrenia. After being released, he continued to associate with his old friends, who did what they could to help him. His paintings had become rather distorted, but his earlier works were shown at exhibitions in Paris and Berlin, thanks to arrangements made by Richard Bergh and Georg Pauli, and he received several medals for them. As the years progressed, his physical health declined. First he suffered from rheumatic problems, which prevented him from painting. Then he was diagnosed with diabetes, which was the cause of his death in 1906.

Legacy

A street, “Ernst Josephsons väg” in Södra Ängby is named after him. His works may be seen at the Nationalmuseum, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde and the Göteborgs konstmuseum.

SELECTED EXHBITIONS

Works by Ernst Josephson can be found in the permanent collections of several important museums. The National Museum of Sweden in Stockholm has a particularly large collection.

- 2000 Ordrupgaard Museum, Charlottenlund, Denmark 1/14/2000 – 4/24/2000

- 1992 Borås Konstmuseum, Sweden, Borås, Sweden, 3/15 – 5/17/1992

- 1991 Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, 11/14/1991 – 3/1/1992

- 1979 Ernst Josephson 1851 – 1906. Bilder und Zeichnungen, Museum Bochum, 5/19 – 6/20/1979

- 1979 Ernst Josephson 1851 – 1906. Bilder und Zeichnungen. Städtisches Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany, 3/22 – 5/6/1979

- 1947 Exhibition of drawings by the Swedish painter Ernst Josephson : From the collection of Dr. Sten Lindeberg of Stockholm. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH, USA, November – December, 1947

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS

- Brummer, Hans Herman. Ernst Josephson – målare och diktare. Stockholm: Norstedts, 2001.Forster, Edmund. „Über Josephsons Bilder während der Krankheit.“ Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst, vol. 21, 1910, pp. 175–177.

- Fastert, Sabine. „Antworten auf Max Nordau. Künstlerische Kreativität als Produkt psychischer Schwellenzustände in den Kunstzeitschriften um 1900.“ In: Volker Hess and Heinz-Peter Schmiedebach (eds.), Am Rande des Wahnsinns: Schwellenräume einer urbanen Moderne. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau, 2012, pp. 175–206.

- Hofmann, Karl-Ludwig and Thomas Röske. „Ernst Josephson – ein verfrühter Expressionist.“ In: Guratzsch, Herwig (ed.): Expressionismus und Wahnsinn. Exhibition catalogue Schloss Gottorf. Schleswig, München, 2003, pp. 68–75.

- Mesterton, Ingrid (ed.). Ernst Josephson (1851–1906). Bilder und Zeichnungen. Exhibition catalogue Städtisches Kunstmuseum Bonn. Bonn, 1979.

- Struck, Hermann. „Ernst Josephson.“ Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst, vol. 20, 1908/09, pp. 243–247.

Source: Wikipedia

Their work is currently being shown at Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde in Stockholm. Numerous key galleries and museums such as Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall have featured Ernst Josephson’s work in the past.

Ernst Josephson’s work has been offered at auction multiple times, with realized prices ranging from $295 USD to $476,672 USD, depending on the size and medium of the artwork. Since 2002 the record price for this artist at auction is $476,672 USD for Den fjortonde juli (July 14th), sold at Bukowskis, Stockholm in 2019.

Ernst Josephson has been featured in articles for Daily Art Magazine and BBC News. The most recent article is Artists and Industrial Revolution: Images of the Changing World written for Daily Art Magazine in December 2020.

The artist died in 1906.

Source: mutualart.com

Ernst Josephson sojourned in Spain in 1881– 82 together with several Nordic colleagues. Young artists travelled there to experience the colourful folk life and not least to see the Spanish masters Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya in the museums. Josephson created two versions of Spanish Blacksmiths, considered to be a highlight from his realistic period. In a letter, he recounted the genesis of the work as follows:

“What most captivated me as a subject were two smiths and a woman who stood outside the smithy grimacing toward the sun. They themselves asked me whether I wanted to paint them that way, and the next day I stood there with a large canvas and painted for fourteen days on the sunny farm.”

It was in the Romani quarter of Triana in Seville that Josephson encountered the three gitanos, whose roughness is underlined by the artist’s bold brushstrokes and whose dark skin, hair, and eyes are emphasized by their positioning in front of a bright limestone wall. The painting creates an immediate sense of intense sunlight, and we understand that we are in more southerly climes.

When Spanish Blacksmiths was displayed for the first time in 1885, its brutal honesty offended critics and the general public alike. The free-spiritedness and saucy vitality exhibited by the three raggedly dressed workers was probably perceived as a threat to middle-class ideals and behaviour.

Ernst Josephson’s career was one of two halves: before and after he became mentally ill. He was diagnosed with paranoia in 1888 and committed to a hospital, although he continued to work as an artist and create significant works. He also wrote poems after becoming ill.

Text: Vibeke Waallann Hansen

From “Highlights. Art from Antiquity to 1945”, Nasjonalmuseet 2014, ISBN 978-82-8154-088-0

Source: nasjonalmuseet